In 1993, Robin Williams sat down with The Today Show and vented his frustration at Disney for breaking what he thought was a simple promise.

Williams said on the NBC show:

“We had a deal. The one thing I said was I will do the voice. I’m doing it because I want to be part of this animation tradition. I want something for my children. One deal is, I just don’t want to sell anything — as in Burger King, as in toys, as in stuff.”

Williams had agreed to voice Genie in Aladdin only if Mickey Mouse didn’t use his performance for product merchandising. When the mouse went ahead anyway, using his voice in commercials and even overdubbing it to sell merchandise, he was furious.

Williams continued on:

“Then all of a sudden, they release an advertisement—one part was the movie, the second part was where they used the movie to sell stuff. Not only did they use my voice, they took a character I did and overdubbed it to sell stuff. That was the one thing I said: ‘I don’t do that.’”

More than thirty years later, another line is being crossed—this time not by Disney, but by fans using artificial intelligence to digitally resurrect the late comedian, and worse, to harass his own family with his image.

Taking a stand, Zelda Williams—Robin’s 36-year-old daughter and the director of Lisa Frankenstein—took to Instagram this week with a clear message: please stop.

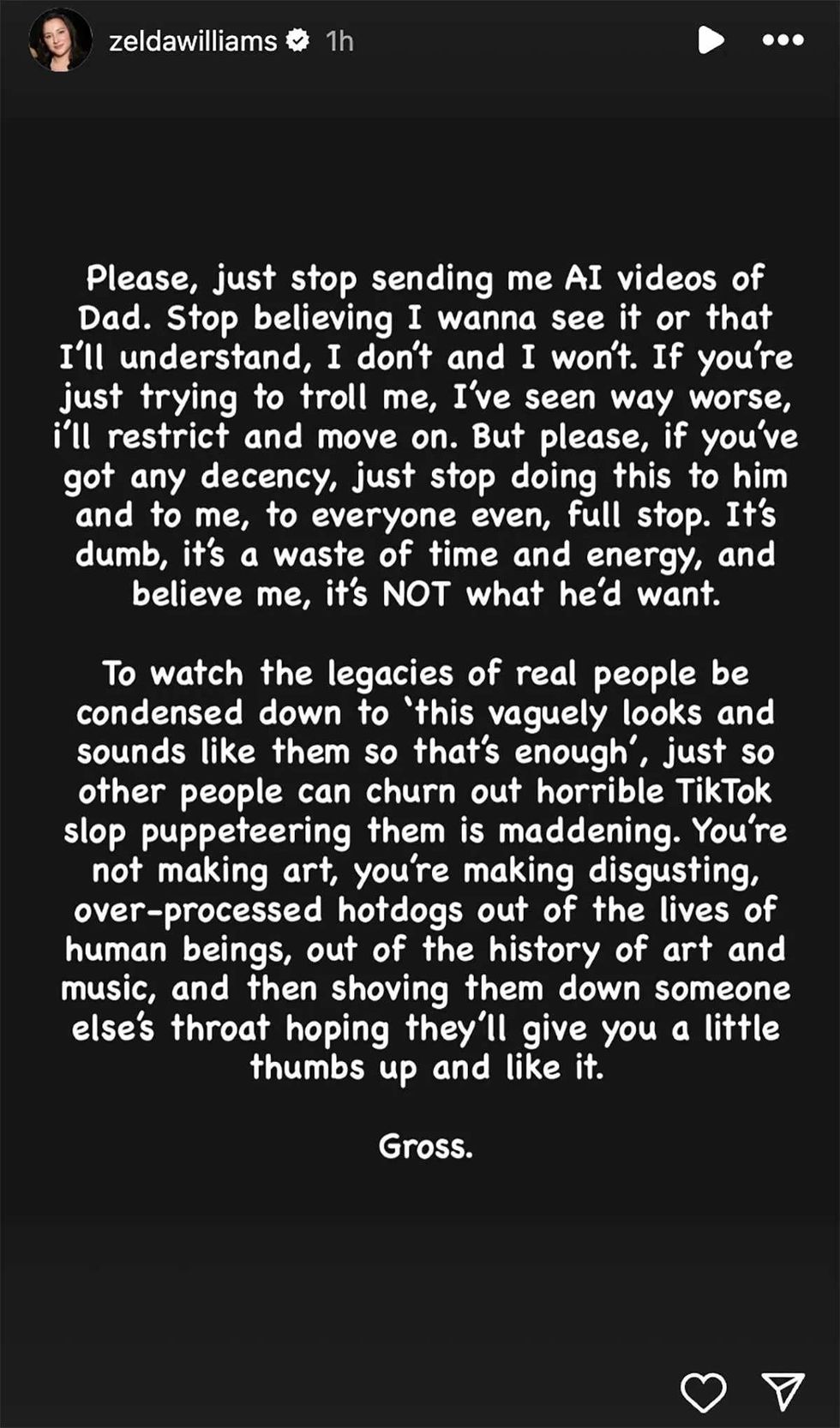

Zelda posted a two-part post on her Instagram Stories last Monday:

“Please, just stop sending me AI videos of Dad. Stop believing I wanna see it or that I'll understand — I don't and I won't. If you're just trying to troll me, I've seen way worse, I’ll restrict and move on. But please, if you’ve got any decency, just stop doing this to him and to me, to everyone even, full stop. It’s dumb, it’s a waste of time and energy, and believe me, it’s NOT what he’d want.”

Her post arrived amid a flood of AI-generated videos that mimic the voices and faces of deceased celebrities, from Elvis Presley to Anthony Bourdain, for viral “what-if” clips and faux tributes.

An example circulating online shows a likeness of Robin Williams generated through the Sora app. This new OpenAI video tool can create photorealistic scenes and avatars from text prompts, often without permission from the estates or rights holders.

You can view the controversial TikTok here:

What is Sora, you may ask? It’s a newly released, app-based video generator from OpenAI that turns short text prompts into hyperrealistic, AI-created videos—even letting users insert their own photorealistic avatars into the scenes.

Major studio executives and talent agency chiefs have also voiced alarm over Sora—now in its second iteration, Sora 2—which has already raised red flags in Hollywood.

Industry leaders worry about how easily likenesses can be replicated and distributed without consent. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has promised to give creators “more granular control” over their intellectual property, but Hollywood isn’t exactly holding its breath.

As for Zelda, those clips aren’t tributes. They’re exploitation.

She continued on:

“To watch the legacies of real people be condensed down to ‘this vaguely looks and sounds like them so that’s enough,’ just so other people can churn out horrible TikTok slop puppeteering them is maddening.”

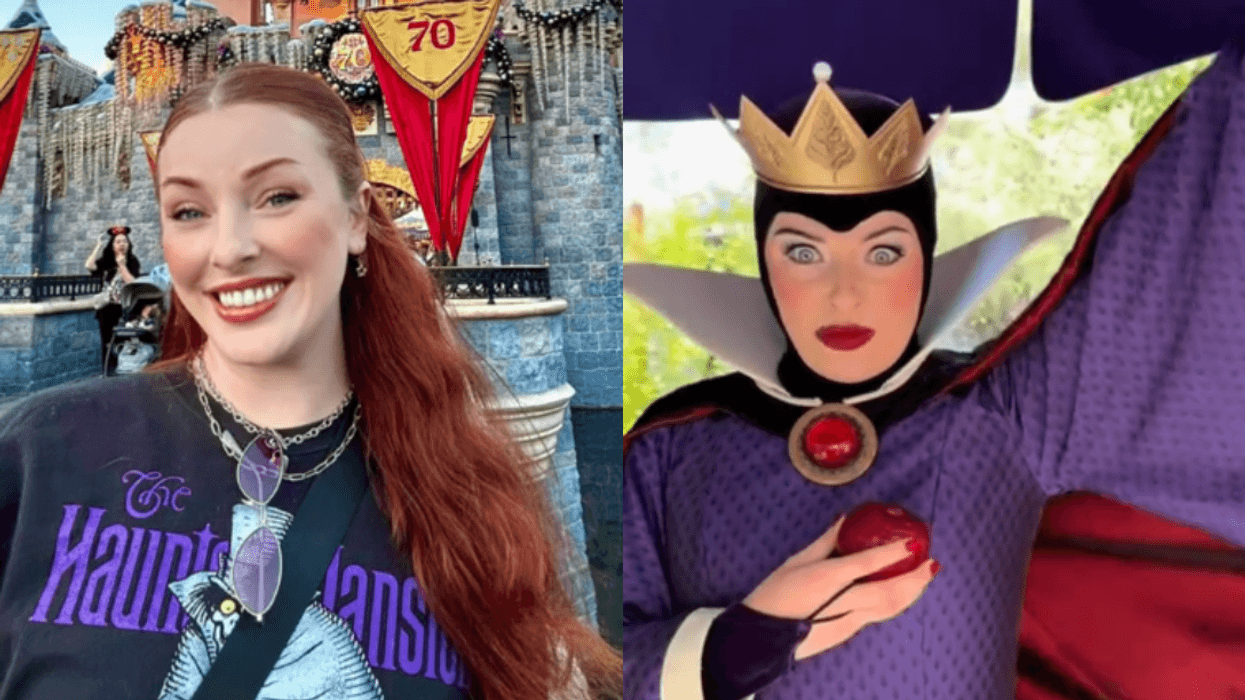

You can view Zelda's posts below:

This isn’t the first time she’s spoken up about her father’s legacy being misused. Last year, Mrs. Doubtfire actor Matthew Lawrence told Entertainment Weekly it would be “cool” to have Robin’s voice serve as “the next voice of AI.”

Lawrence explained:

“I would love — now, obviously, with the respect and with the okay from his family — but I would love to do something really special with his voice because I know for a generation, that voice is just so iconic.”

Zelda’s answer now seems more definitive: absolutely not.

Her father, known for films such as Aladdin, Robots, Happy Feet, Good Will Hunting, and Mrs. Doubtfire, died in August 2014 at the age of 63. He was survived by his widow, Susan Schneider, and his sons, Zak and Cody Williams, as well as his daughter, Zelda.

His battle for creative control wasn’t new. The Disney fallout led him to skip the direct-to-video flop The Return of Jafar, with The Simpsons’ Dan Castellaneta stepping in. Williams only returned for the third film after the studio issued a public apology—and reportedly gifted him a Picasso painting.

Zelda hasn’t softened her stance on the larger issue either:

“You’re not making art. You’re making disgusting, over-processed hotdogs out of the lives of human beings, out of the history of art and music, and then shoving them down someone else’s throat hoping they’ll give you a little thumbs up and like it. Gross.”

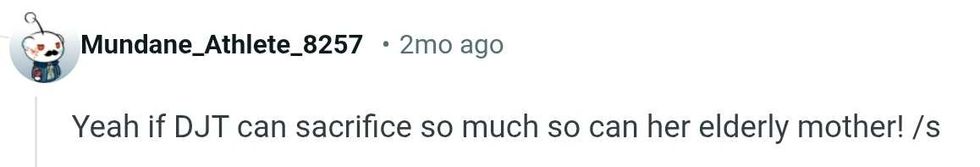

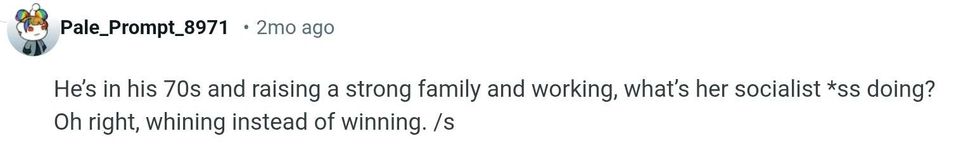

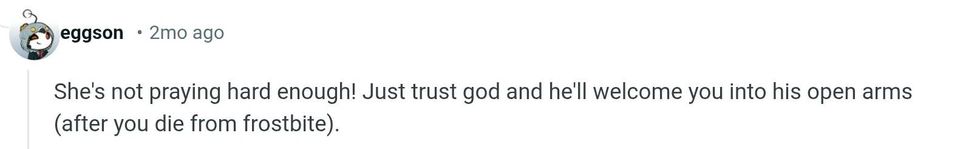

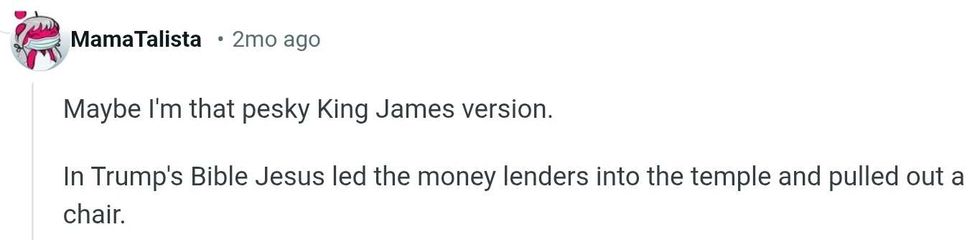

Gross indeed—and social media agreed:

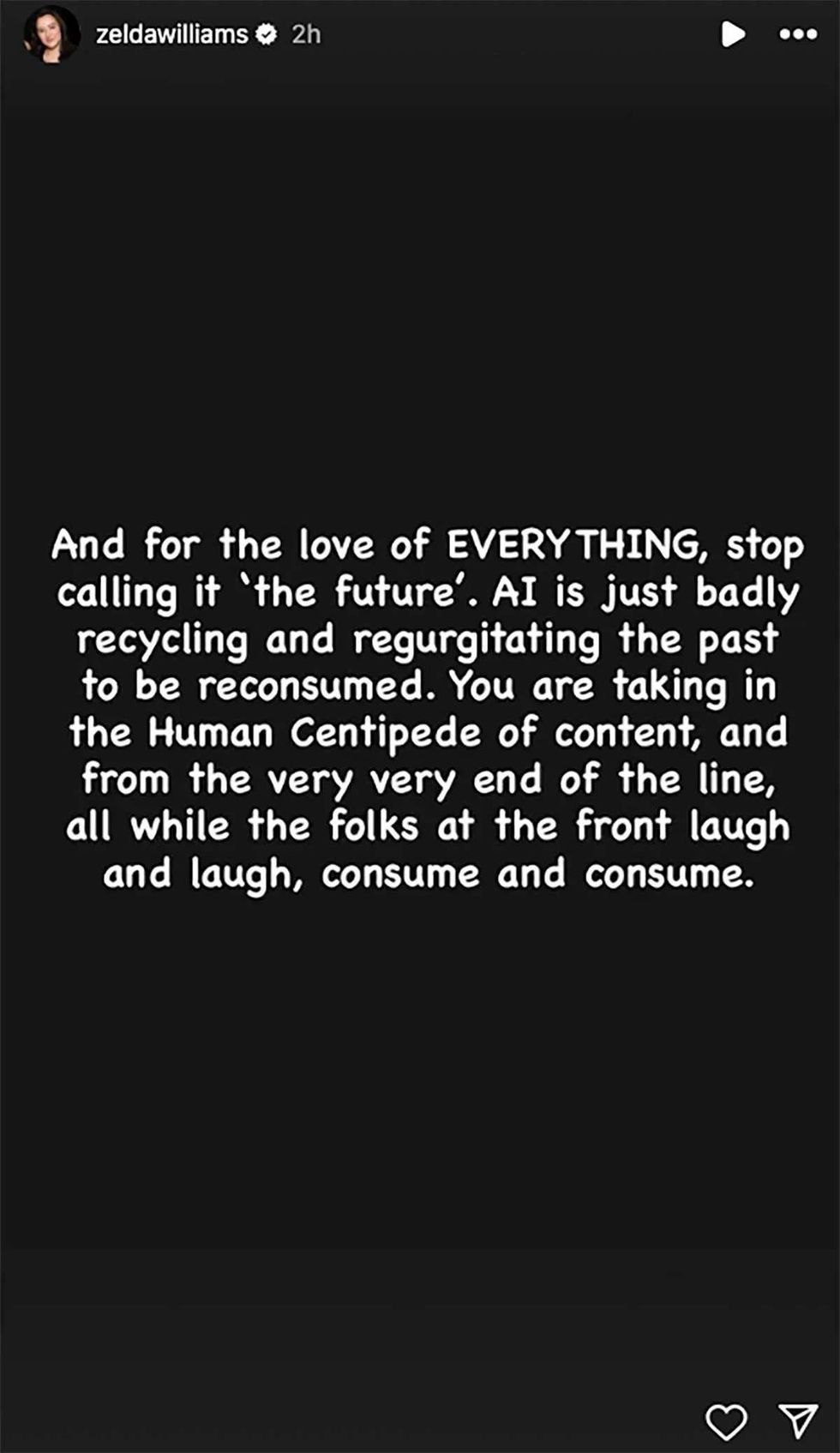

Zelda later posted one more message to her followers, her most biting yet:

“And for the love of EVERYTHING, stop calling it ‘the future.’ AI is just badly recycling and regurgitating the past to be re-consumed. You are taking in the Human Centipede of content, and from the very very end of the line, all while the folks at the front laugh and laugh, consume and consume.”

Her frustration mirrors a broader debate over digital resurrection. AI “holograms” have been appearing everywhere, from concerts to documentaries. Former CNN host Jim Acosta even aired an interview with a hologram of Parkland shooting victim Joaquin Oliver to raise awareness about gun violence, a moment that blurred the line between memorial and marketing.

And this past summer, Rod Stewart drew backlash for featuring AI-generated likenesses of Ozzy Osbourne and other late musicians during a televised tribute.

Back in 1993, Robin Williams warned the world about corporations profiting from his voice without consent. Three decades later, his daughter is fighting the same battle—only now, it’s not just about toys or ads or social media clout.

It’s about preserving what’s left of a human legacy in an increasingly artificial world.

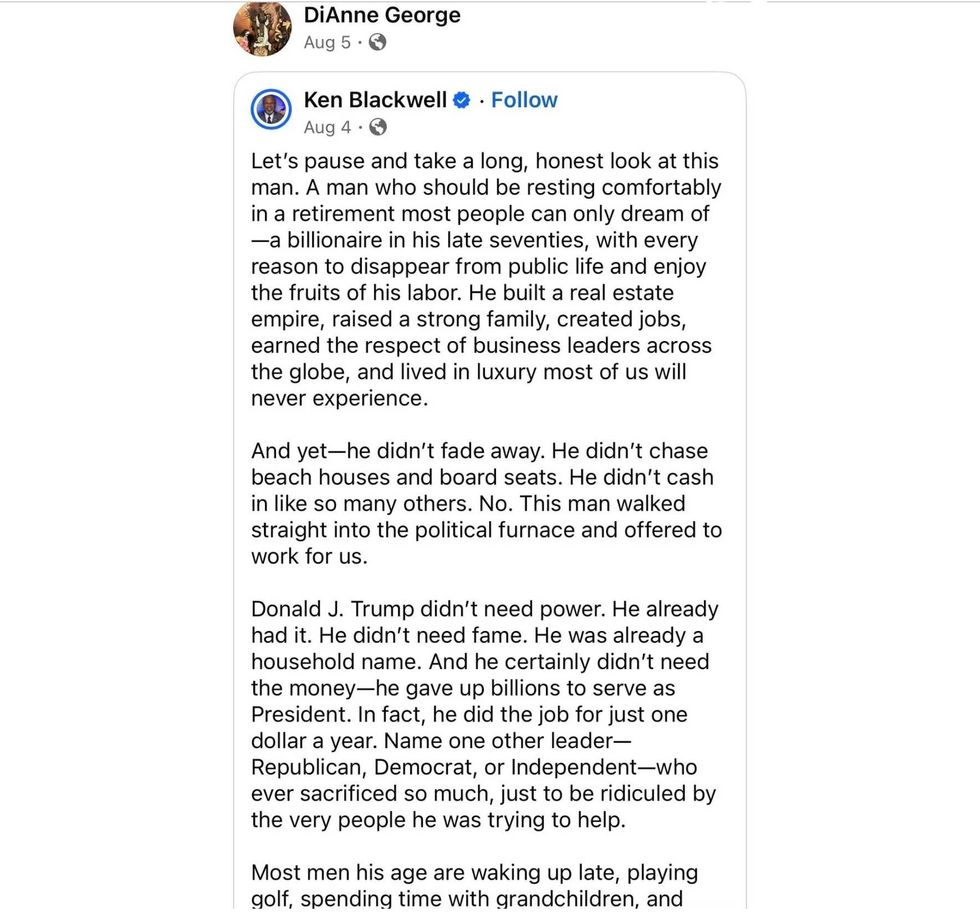

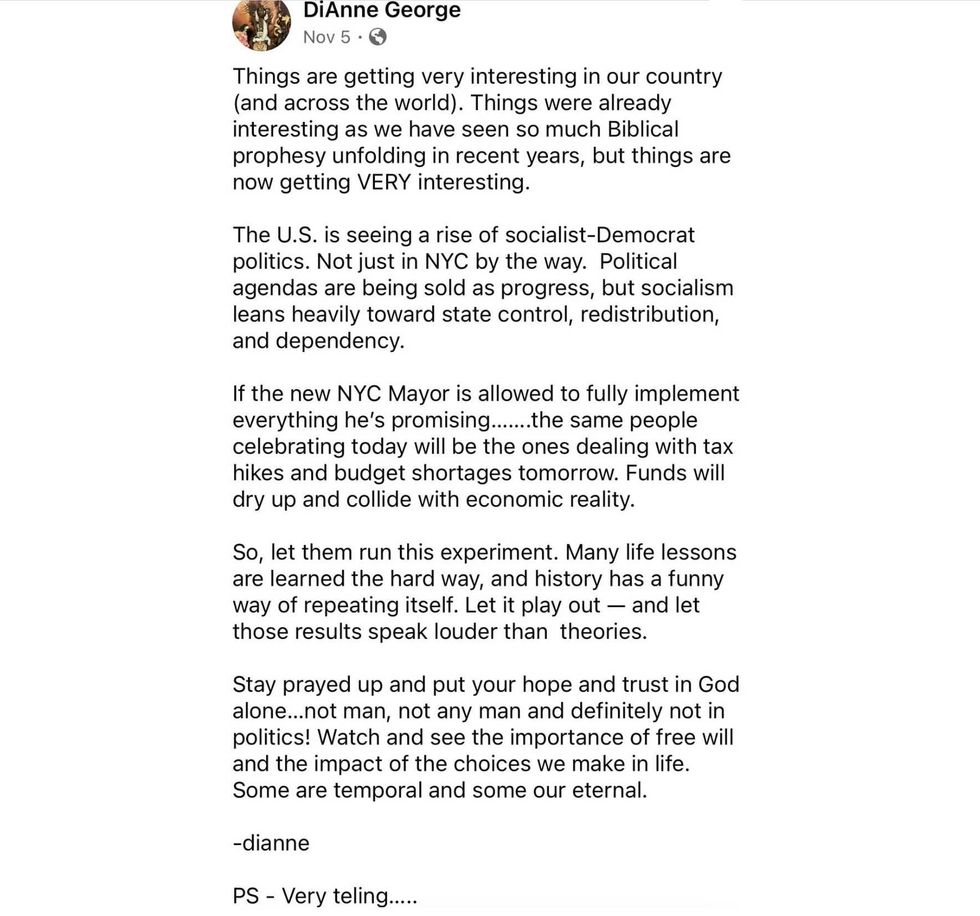

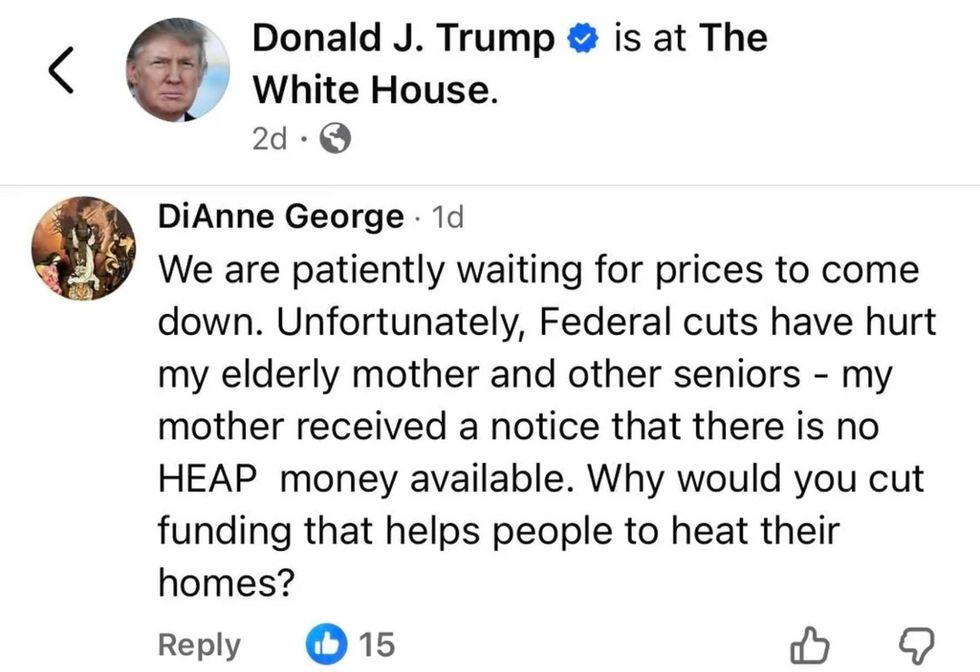

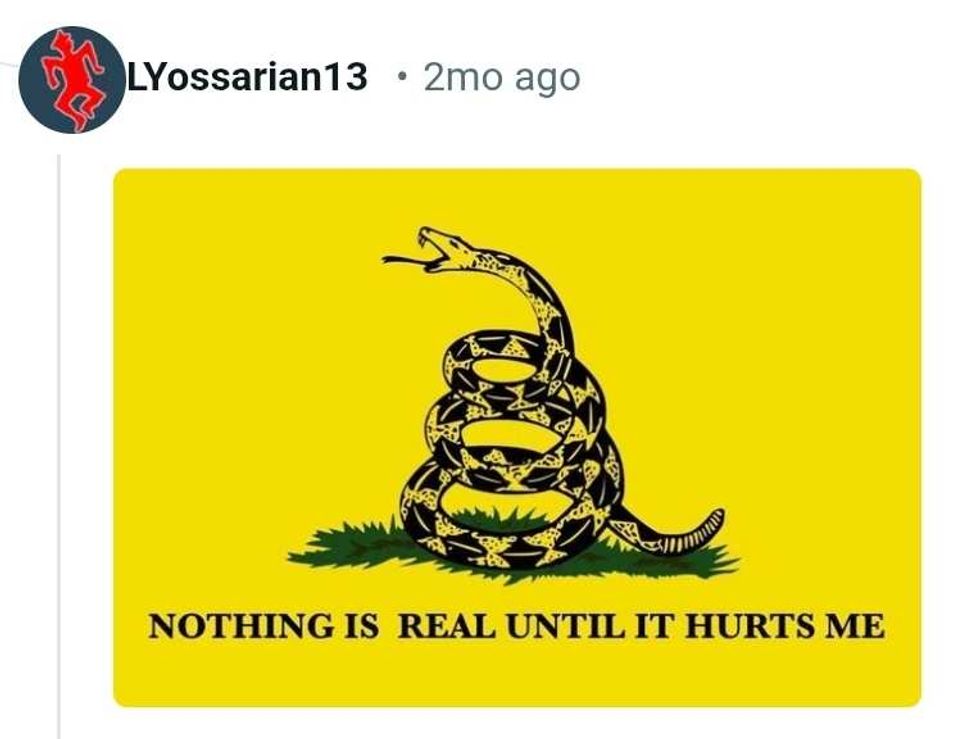

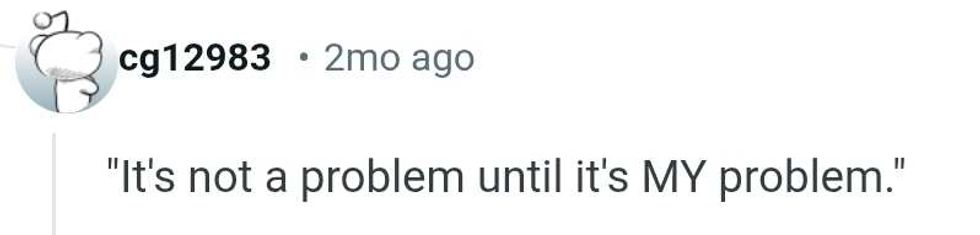

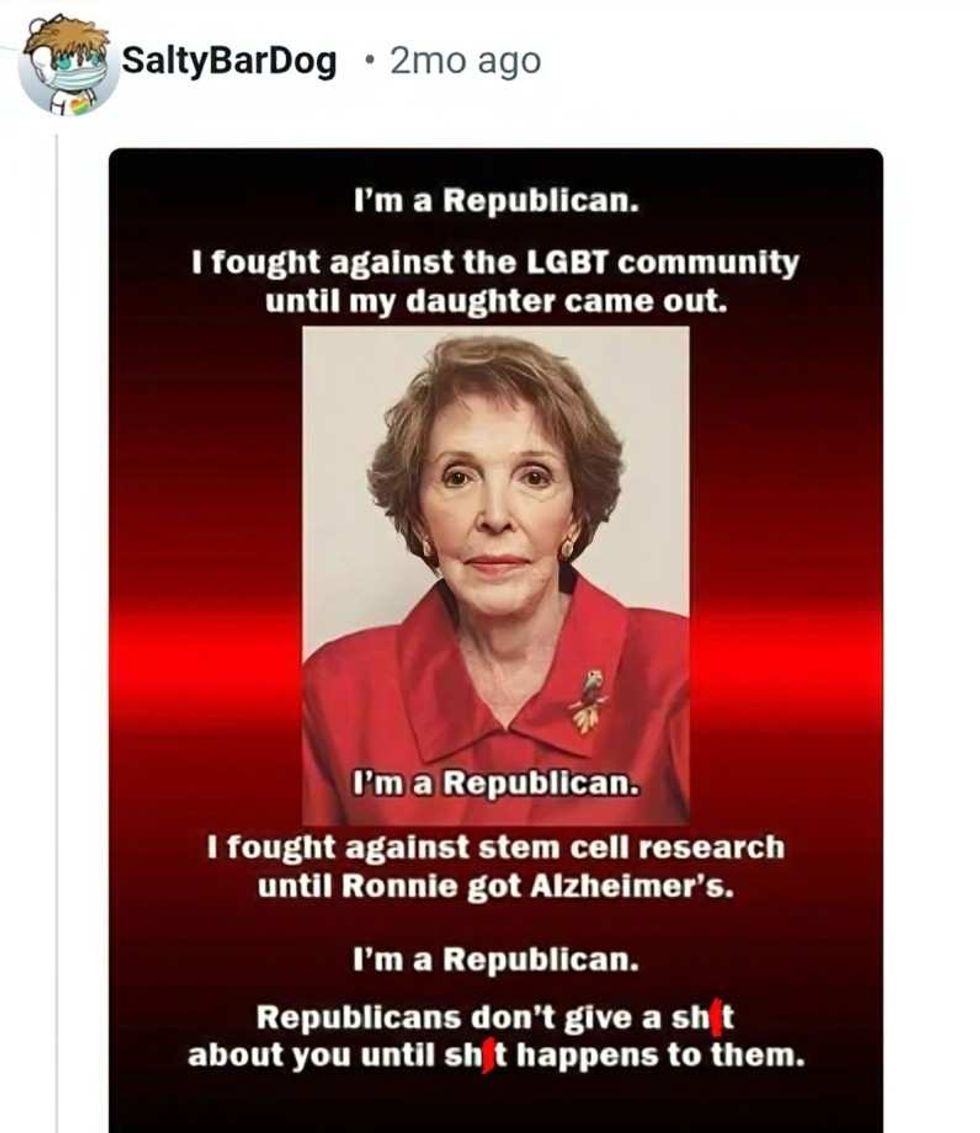

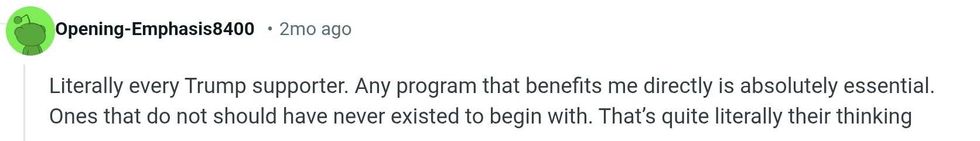

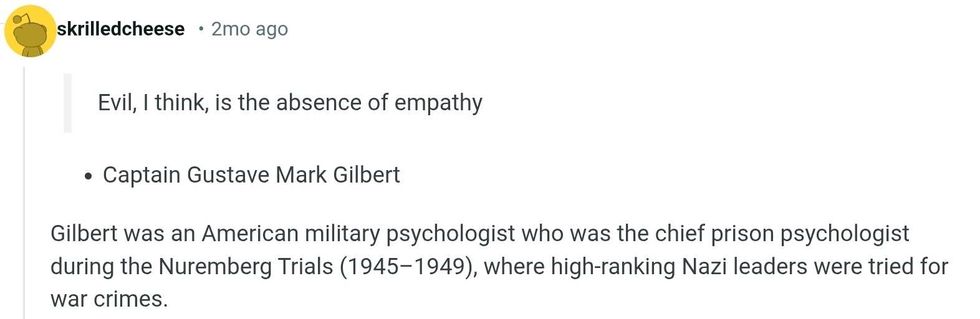

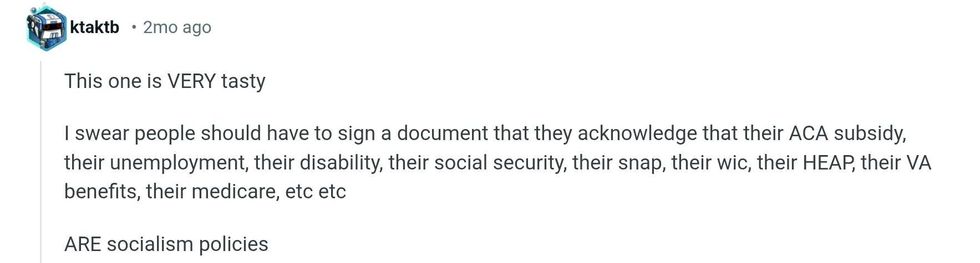

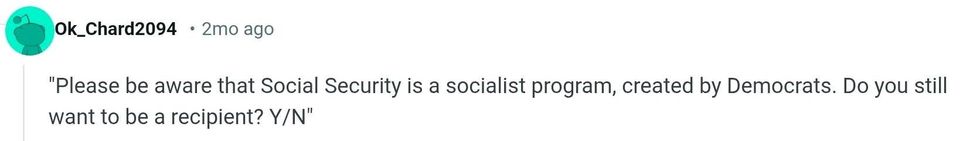

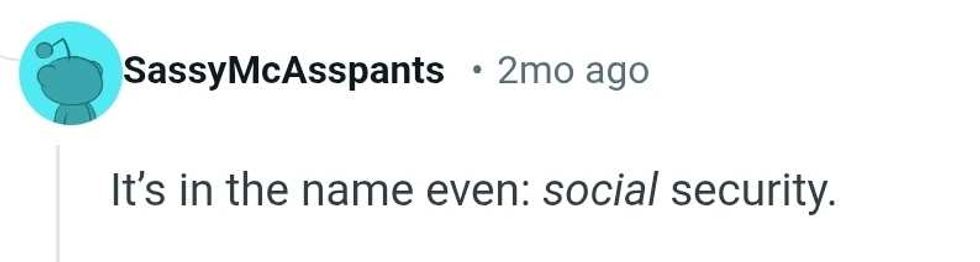

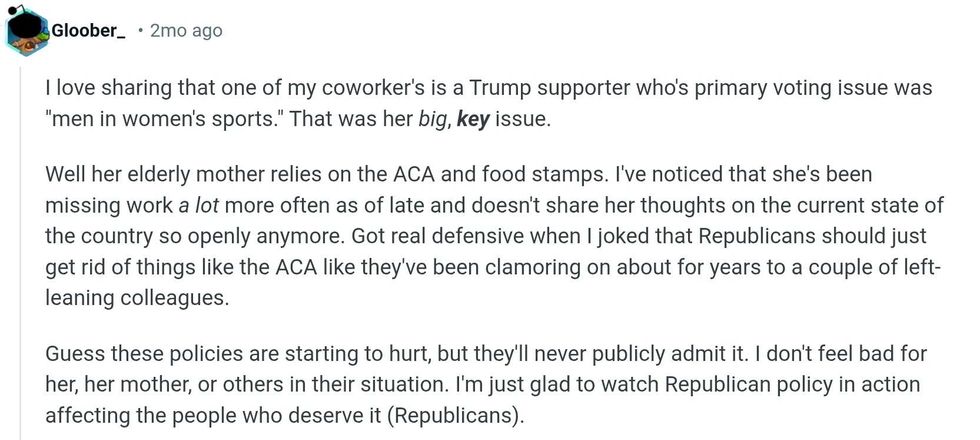

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

@meidastouch/X

@meidastouch/X @meidastouch/X

@meidastouch/X @meidastouch/X

@meidastouch/X @meidastouch/X

@meidastouch/X

illustrate margot robbie GIF

illustrate margot robbie GIF

Bbc One Love GIF by BBC Three

Bbc One Love GIF by BBC Three  Oh Yeah Dancing GIF by Jennifer Accomando

Oh Yeah Dancing GIF by Jennifer Accomando