At the age of 76, Linda Brown, the African American woman at the center of the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, has passed away. Brown was only eight-years-old when her father, Rev. Oliver Brown, sued the school district for denying her admission into an all-white elementary school. With the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s Special Counsel Thurgood Marshall representing Oliver and Linda Brown, the Supreme Court ultimately ruled in favor of desegregation, thus putting an end to the concept of “separate but equal.”

Despite speaking out in the 1970s about feeling exploited by the media as a poster child for desegregation, Linda Brown returned to the spotlight in 1979 when the American Civil Liberties Union reopened the Topeka, KS. According to the new case, the ACLU believed the city’s schools were still segregated, a belief that was echoed by the Court of Appeals that ruled in their favor.

To celebrate the life of the young girl that sparked the end of “separate but equal,” read through these facts pertaining to the landmark Supreme Court case and the history of segregation before Brown v. Board of Education.

The Five Cases of Brown v. Board of Education

Though Oliver Brown’s case against the Topeka School District is viewed as an individual suit, there were five total lower lawsuits filed in 1950 and 1951. Suits came out of Kansas, Virginia, Delaware, the District of Columbia, and South Carolina, but only Brown’s was chosen by the Supreme Court. The decision was later explained as being down to avoid looking like the issue was “a purely southern one.”

Though all five of the lower courts refused to act on school desegregation, the appeals that followed provided some silver lining. Judge J. Waties Waring of South Carolina described segregation in education “an evil that must be eradicated.” In Kansas, the court ruled that segregation negatively affected the children.

Racial Segregation was Mandated by 17 States

The concept of racial segregation stretched beyond just the beliefs of the boards of education that enforced it. In 17 states, all in the south and along the border, racial segregation was mandated by the government. Arizona, Kansas, Wyoming, and New Mexico were among four additional states that allowed local communities to set the same requirements. Despite being required, neither local or state governments ensured that these schools were “separate but equal,” as ruled by the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson. Blacks-only schools were found to be lacking necessities like libraries, running water, electricity, and cafeterias.

The Plaintiffs Faced Personal Ramifications

Once the lawsuits were filed, the plaintiffs behind them and their families started to see a drastic change in their quality of life. Some lost their jobs while others came to find that their credit was cut off entirely. It wasn’t uncommon for them to face death threats, either, as seen with Rev. Joseph a DeLaine. DeLaine of South Carolina had his house and church burned down by whites and was forced to flee the state. Judge Waring also received multiple threats and retired in 1952 following the backlash.

The Decision Was Unanimous

Segregation may have seemed like a hot-button issue that nobody would speak out against, but when Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka gained steam, it garnered plenty of support. At the forefront was Chief Justice Earl Warren, who persuaded other justices that “separate but equal” was antiquated, archaic, and should be overturned. Warren worked tirelessly to get everybody on his side, even those that were initially on the fence about the issue.

When the ruling came through, all nine members of the court agreed with Warren. The ruling that was issued stated that “the very foundation of good citizenship” was education. It went on to say: “To separate [black children] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community.”

President Eisenhower Didn’t Support the Court’s Decision

While the U.S. Department of Justice directly supported the position of the Supreme Court’s ruling, President Dwight D. Eisenhower was less understanding. As the case was being considered, Eisenhower reportedly told Chief Justice Earl Warren that southern whites “[were] not all bad people.” When the decision came through in favor of desegregation, the president was hesitant to use his authority to enforce the court’s ruling.

Awkward Pena GIF by Luis Ricardo

Awkward Pena GIF by Luis Ricardo  Community Facebook GIF by Social Media Tools

Community Facebook GIF by Social Media Tools  Angry Good News GIF

Angry Good News GIF

Angry Cry Baby GIF by Maryanne Chisholm - MCArtist

Angry Cry Baby GIF by Maryanne Chisholm - MCArtist

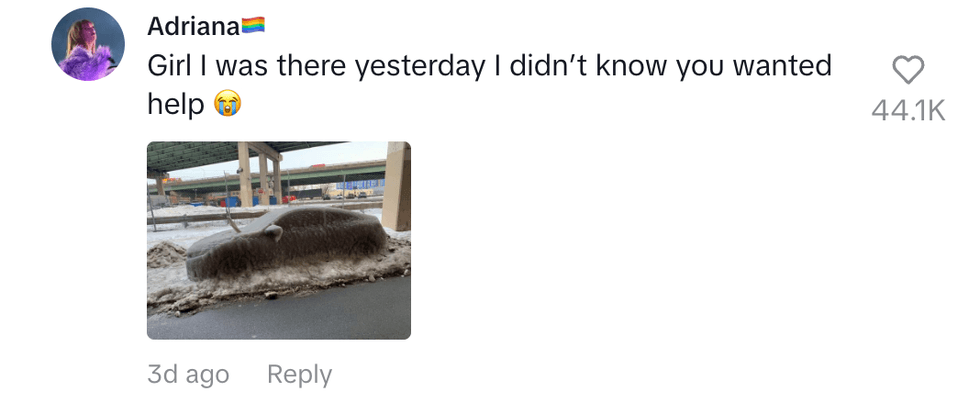

@adriana.kms/TikTok

@adriana.kms/TikTok @mossmouse/TikTok

@mossmouse/TikTok @im.key05/TikTok

@im.key05/TikTok @biontrtwff101/TikTok

@biontrtwff101/TikTok @likebrifr/TikTok

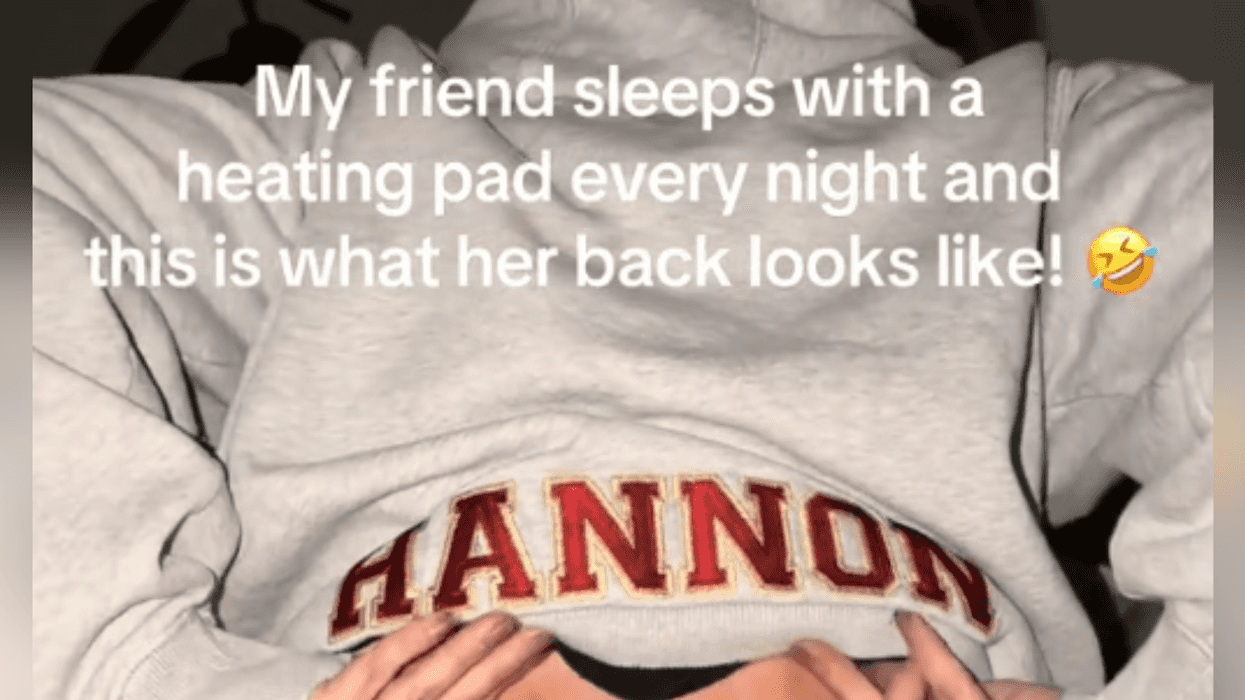

@likebrifr/TikTok @itsashrashel/TikTok

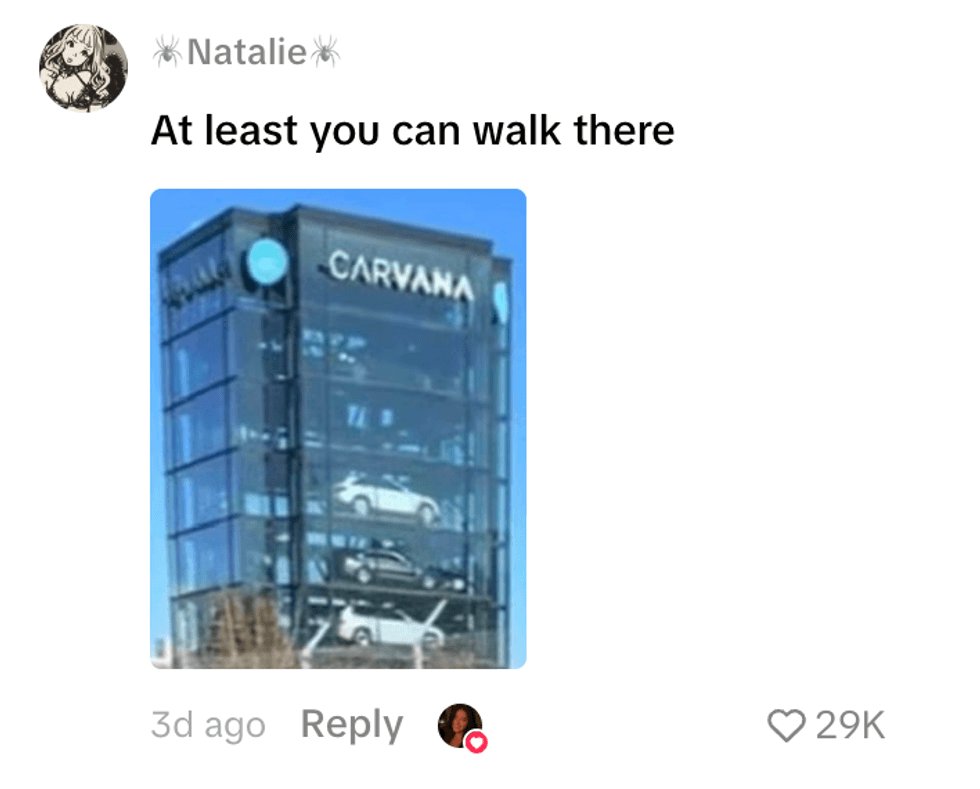

@itsashrashel/TikTok @ur_not_natalie/TikTok

@ur_not_natalie/TikTok @rbaileyrobertson/TikTok

@rbaileyrobertson/TikTok @xo.promisenat20/TikTok

@xo.promisenat20/TikTok @weelittlelandonorris/TikTok

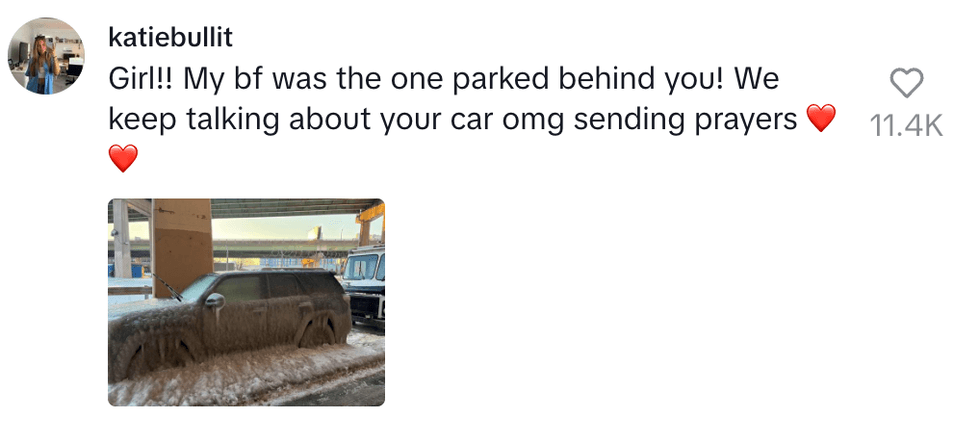

@weelittlelandonorris/TikTok @katiebullit/TikTok

@katiebullit/TikTok @rube59815/TikTok

@rube59815/TikTok

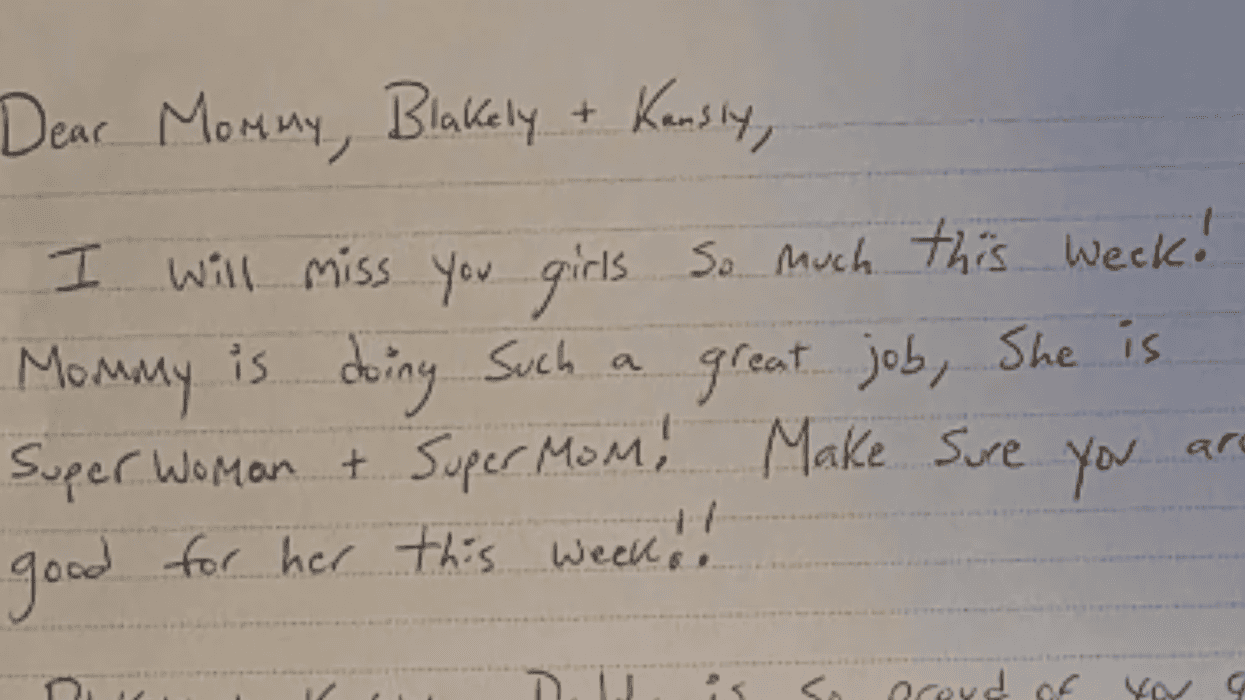

u/Fit_Bowl_7313/Reddit

u/Fit_Bowl_7313/Reddit

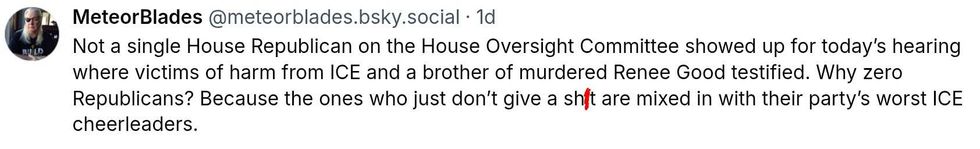

@meteorblades/Bluesky

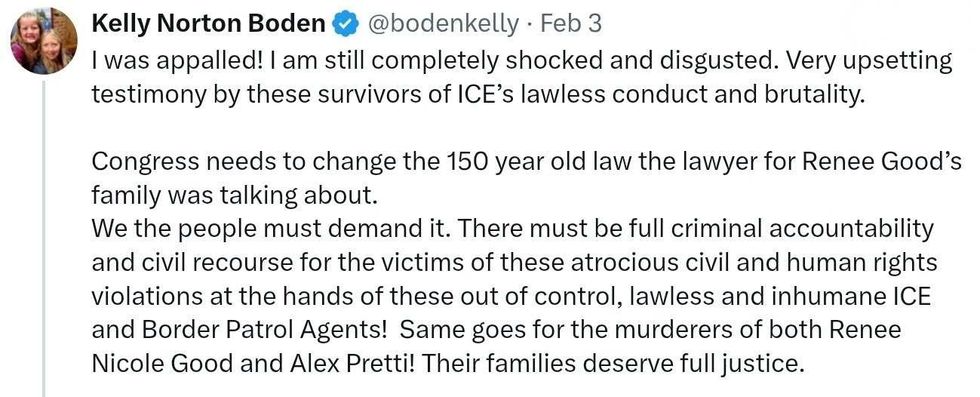

@meteorblades/Bluesky @bodenkelly/X

@bodenkelly/X