For some time, few people took the notion of an electric bus seriously. In 2011, Chinese automotive manufacturer BYD Co. revealed an early model at an industry conference in Belgium, and was met with laughter.

Isbrand Ho, managing director of BYD in Europe, remembered the laughter from that day directed at BYD for “making a toy,” but continued, “And look now. Everyone has one.”

Presently, and in a relatively short period of time, battery-powered buses have progressed to serious contenders in changing city transportation for good, as well as a strong addition to the reconfiguration of the energy industry on a global scale.

It is unusual that this powerhouse of a concept was conceived and initially put forth in China — where carbon emissions run high and air quality is at a fairly consistent low — yet, the concept is already beginning to disintegrate demands for fossil fuel.

In 2017, China had about 99 percent of the 385,000 electric buses on roads in their possession, which is 17 percent of the country’s entire supply of buses. Every five weeks, Chinese cities add 9,500 zero-emissions buses to their supply, or about as many buses as London’s entire operational fleet, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF).

An average bus consumes 30 times the fuel of an average car, and thanks to electric buses, the demand for fuel is decreasing. However, this is hurting the fuel industry.

According to BNEF calculations, for every 1,000 battery-powered buses on the road, about 500 barrels a day of diesel fuel will go unused; for 2018, the volume of unneeded fuel may rise 37 percent to 279,000 barrels per day — 233,000 being from electric buses alone — due to electric transport, which also includes cars and light trucks. This is roughly about as much oil as Greece consumes, according to BNEF.

Colin McKerracher, head of advanced transport at the London-based research unit of Bloomberg LP, said on the matter, “This segment is approaching the tipping point. … City governments all over the world are being taken to task over poor urban air quality. This pressure isn’t going away, and electric bus sales are positioned to benefit.”

China, which for some time was notorious for worst pollution rates in the world, is growing in urban population and therefore rising in demand for energy. The need for electric automobiles or other emissions-reducing solutions is high, as smog resulted in 1.6 million deaths in 2015, according to Berkeley Earth, an environmental nonprofit.

Ten years ago, Shenzhen was booming and the environment was not a primary concern. Infamous for the smog that accompanied its profitable businesses, the Chinese government selected the city to participate in a program for energy conservation and zero emissions vehicles in 2009. In the following two years, the first electric buses made their appearances off of BYD’s production line.

BYD, holding 13 percent of China’s electric bus market in 2016, sent 14,000 vehicles to the streets of Shenzhen — and 16,359, as of this past May. Thus far, the company has built 35,000 buses and can build up to 15,000 annually, according to Ho, and the company also estimates its buses have traveled 17 billion kilometers, or 10 billion miles, and saved 6.8 billion liters, or 1.8 billion gallons, of fuel since inception. Ho explained that these numbers equate to 18 million tons of carbon dioxide pollution averted, the equivalent of roughly that which 3.8 million cars generate each year.

“The first fleet of pure electric buses provided by BYD started operation in Shenzhen in 2011. Now, almost ten years later, in other cities, the air quality has worsened, while — compared with those cities — Shenzhen’s is much better,” Ho told BNEF.

Paris, London, Mexico City, Los Angeles and Oslo, as well as eight other cities, have promised to buy zero-emissions public transportation by 2025. London, for example, is doing so gradually. Presently, four routes in the city center operating with single-decker units are moving to electric. Ideas, like retrofitting 5,000 old diesel buses, are advancing the city toward cleaner public transportation, and toward emission-free buses by 2037.

London’s buses use about 1.5 million barrels of fuel per year. Electric buses in totality would displace 430 barrels of diesel per day for each of 1,000 electric buses. U.K. diesel use would decrease by 0.7 percent, according to BNEF.

As of 2017, across the U.K., there were 344 electric and plug-in hybrid buses. BYD aspires to provide more of these buses and has partnered with a Scottish bus-maker to make the batteries for 11 new electric buses intended for London’s roads in March.

Falkirk-based manufacturer Alexander Dennis Ltd. began making electric buses in 2016 and is the European market leader, with over 170 vehicles running in the U.K. alone.

Ho further explained that London’s transport authority is planning to electrify its iconic double-decker buses: “The tech is ready. We are ready, we have our plants in China, and Alexander Dennis in Scotland is geared up for TfL (Transport for London). Once we’re given the word, we are ready to go.”

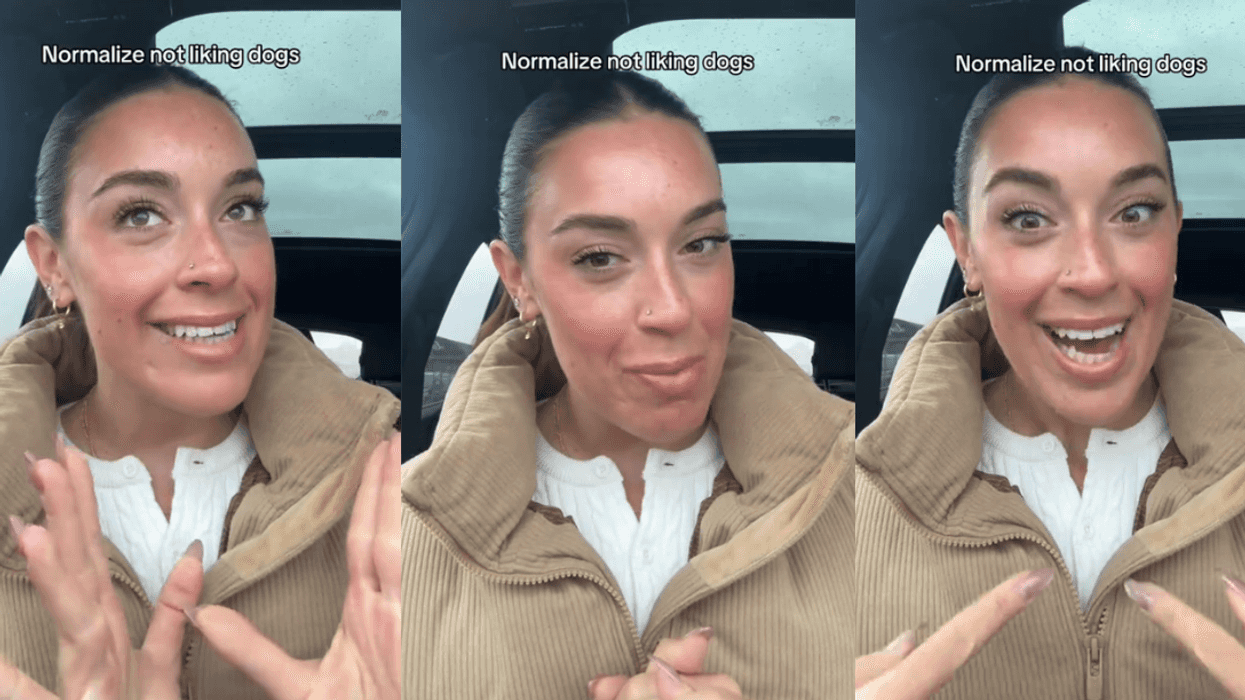

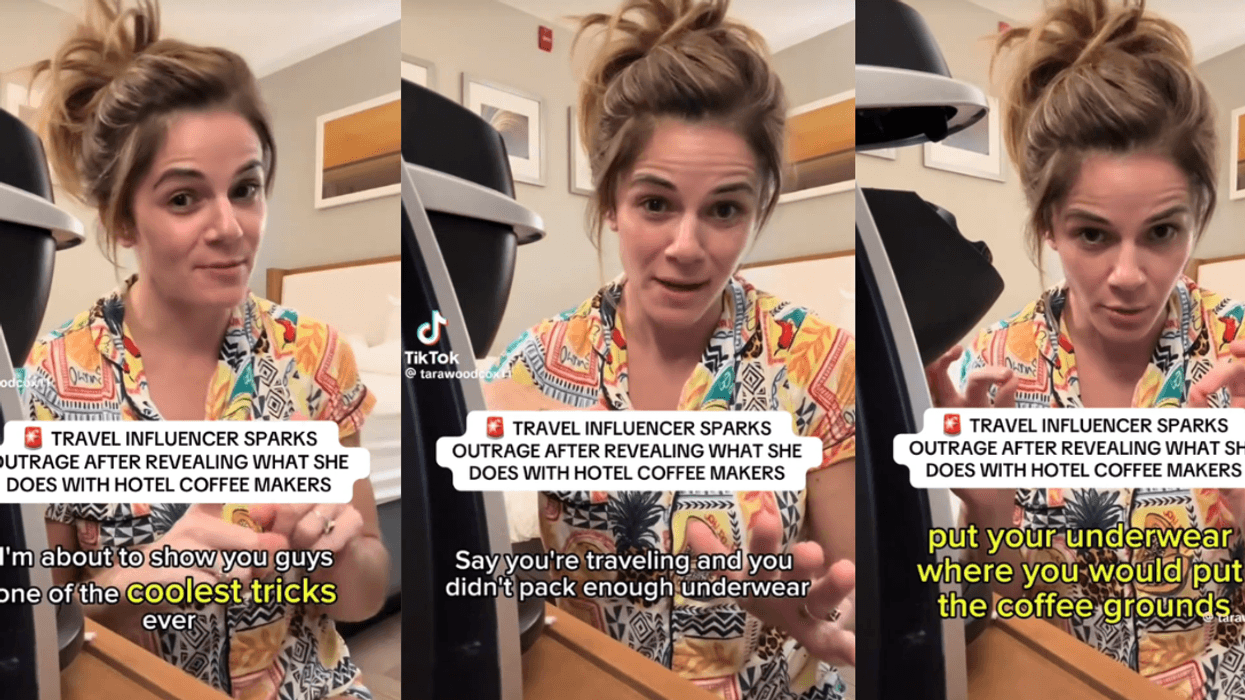

@madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok

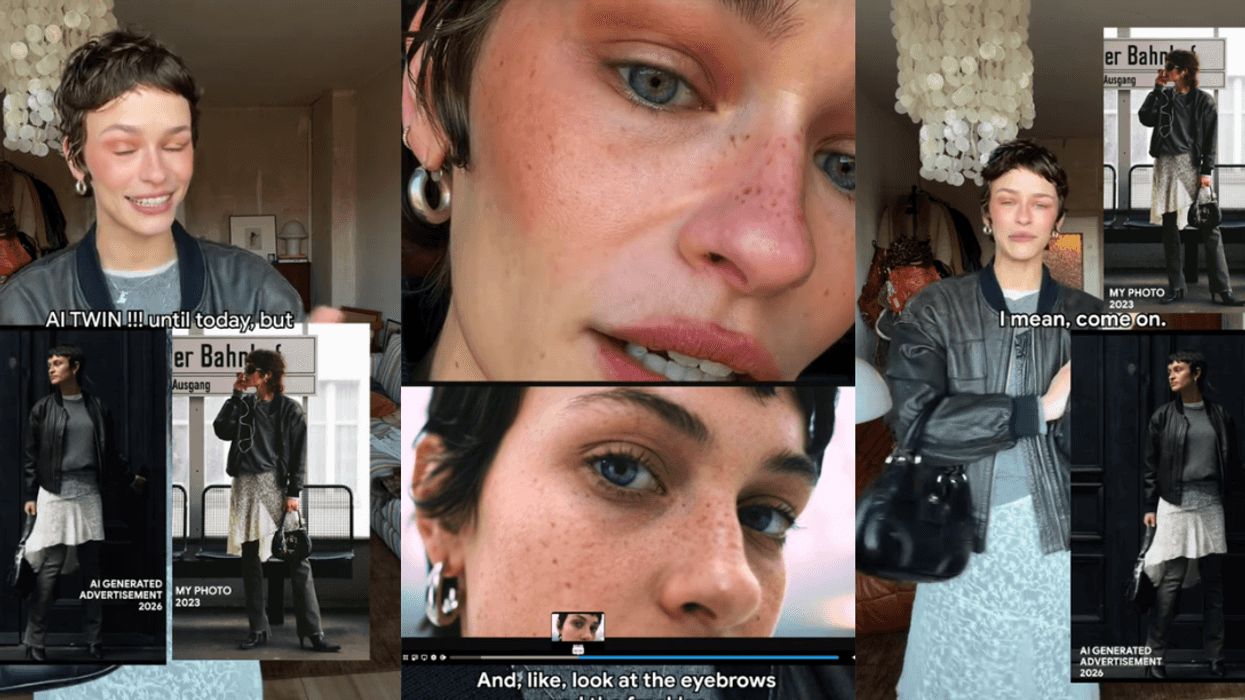

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok