Analysts have begun to dive more deeply into the results of the first post-Roe referendum on abortion rights, which took place in deeply red Kansas on Tuesday and hit like a thunderclap before the upcoming midterms.

The numbers confirm what anecdotal accounts had indicated.

First, voter turnout was way up for a midterm, at around 49 percent, which is near normal election cycle levels and the highest ever turnout for a midterm in the state’s history.

Second, there were one hundred and fifty thousand single issue voters who cast their ballots against the measure but did not vote for the parties’ gubernatorial candidates at all.

And third, while the urban areas of Kansas voted overwhelmingly against the measure as expected, the numbers in rural GOP strongholds showed that abortion bans are deeply unpopular across the whole state (and by extension, across the country).

Democrats are hoping to take and learn from that outpouring of activism and energy and put abortion front and center this November. The New York Times featured some notable quotes from leading Democrats in its post-referendum reporting.

Said President Joe Biden:

“The court practically dared women in this country to go to the ballot box to restore the right to choose.”

He continued:

“They don’t have a clue about the power of American women.”

Democratic Representative Sean Patrick Maloney of New York , who chairs the House Democratic campaign arm, echoed this sentiment, saying Kansas was only a “preview of coming attractions” for Republicans.

Democratic Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts urged a “full-throated” support by her party of abortion access, while Rep. Elissa Slotkin, a Michigan Democrat in a key swing district, declared that abortion access “hits at the core of preserving personal freedom, and of ensuring that women, and not the government, can decide their own fate.”

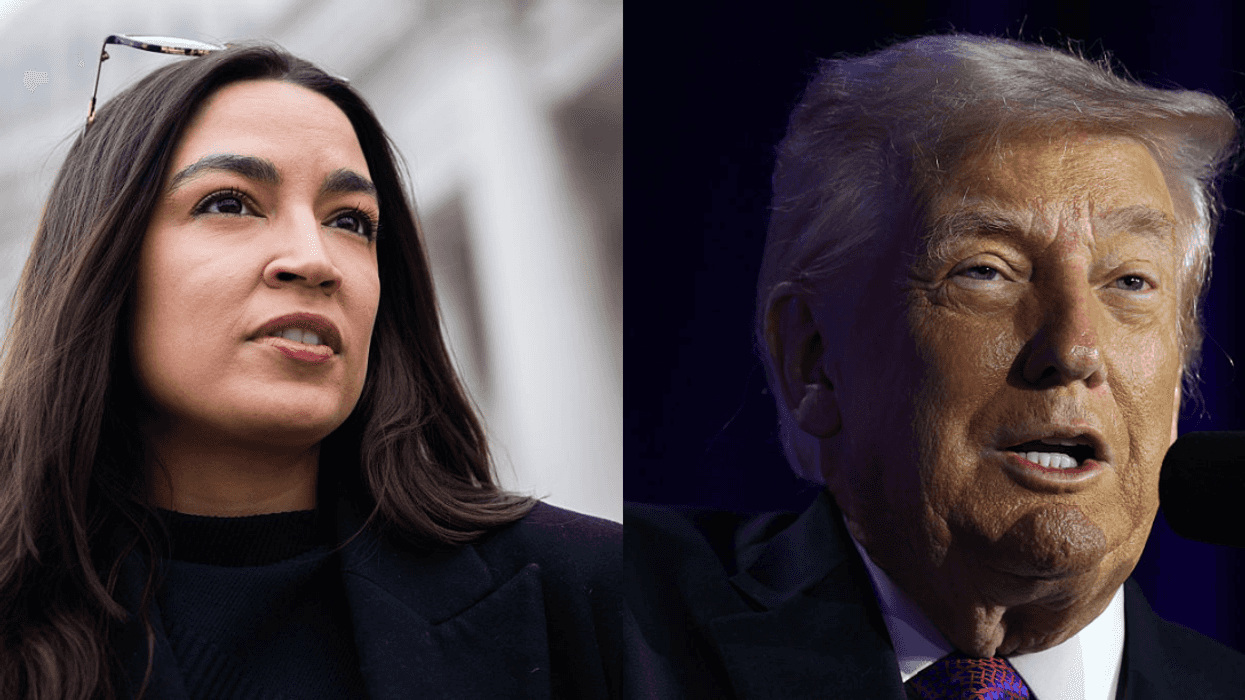

The astonishing pushback against severe abortion restrictions, in a state that has voted for the GOP candidate for President for the last 50 years, opens the intriguing possibility that it can be replicated in other key states and perhaps even nationally. Could the feared red wave turn out instead to be a blue one, riding a swell of anger from the overturning of Roe?

The traditional thinking goes, the incumbent party usually gets blamed and punished in the midterms as voters express their displeasure at the direction of the country. They take their frustrations out at the politicians in power.

But many are wondering which is truly the “party in power.” After all, the most consequential action of late, the thing that affects the most number of Americans, is the Supreme Court’s decision to strike down Roe.

And there is a wide perception that SCOTUS is acting as nothing more than the political arm of the GOP, with six of its justices appointed by Republican Presidents and at least five of those openly waging war on established legal precedent.

Do critical swing district voters really want to hand Congress to the same party that effectively controls the Supreme Court?

Moreover, it seems increasingly clear that Republican lawmakers at both the state and national level have moved to the right of their own base on abortion and other questions such as gun violence and LGBTQ+ rights.

When this happens, a gap can open up into which the opposition can insert a “wedge” issue, as Republicans have done successfully to Democrats on things like police funding and so-called “open borders.”

It certainly makes sense for Democrats to lean in hard on abortion rights and access and to make it a “wedge” issue wherever they can, crossing party lines and bringing out voters as it just did in Kansas. But there are some important caveats and circumstances to consider.

First, in Kansas there was a ballot measure on which the electorate could vote up or down, yes or no. And in that state’s case, proponents had hoped to strip an existing right out of the state constitution.

There was a sense of urgency and immediacy to the measure, one that could galvanize massive numbers of new registrations and election turnout. But only a handful of other states have up-or-down votes on abortion this November, including California, Michigan, Vermont and Kentucky.

Kentucky’s would operate to declare that there is no constitutional right in that state to abortion, while the others would add positive language to enshrine the right in the state constitution. Nowhere could this be more impactful than in Michigan, where Democrats are trying, so far unsuccessfully, to prevent an abortion law written 90 years ago from taking effect.

Without the constitutional amendment, abortion would be rendered essentially illegal in the state due to that existing law. But it is less clear whether voters in California or Vermont, or the 45 other states without any ballot measures on the subject, will turn out in sufficiently high numbers to ensure the protection of abortion rights that are not in imminent danger.

Second, and related to point one, is that in the general election, voters will be looking at many issues, including abortion, which may or may not rank as their top concern. Most voters still remain primarily interested in their pocketbooks, and therefore the state of inflation, the economy, and jobs will and must be the main focus, even while Democrats can gain some traction from single issue voters concerned about the loss of abortion rights.

The Democrats will need to make a strong case that the GOP is an extremist party on all levels, whether it’s about bedrooms, boardrooms, or classrooms.

Republicans are making some of these arguments easier by nominating radical conspiracy mongers and anti-abortion zealots to high office, particularly in swing states like Georgia (with Herschel Walker), Pennsylvania (with Doug Mastriano), Arizona (with Blake Masters), Wisconsin (with Ron Johnson), and Michigan (with Tudor Dixon).

Democrats have an enormous opportunity to show how out of touch these nominees are on abortion, as well as to highlight their “Team Crazy” support of the Big Lie and their dangerous militancy on the Second Amendment.

Third, Democrats need to understand that a sizeable portion of their own base is not necessarily aligned with the party on abortion rights and remains far more concerned with economic issues and immigration. The slide in support for Democrats among Latino voters, particularly among working class Latino families in the South and Southwest, is perhaps the most worrisome development here.

The assumption that all ethnic minorities simply will embrace Democratic messaging around racism, immigration and bodily and sexual autonomy is a dangerously faulty one. Democrats cannot afford to go all-in on abortion rights without continuing to work hard to win over working class families through policies that actually help them financially.

Fourth, and finally, for Democrats to capitalize on the anger and fear generated by the U.S. Supreme Court around the loss of federal abortion rights, they must make the case that the GOP poses an imminent threat to those rights, even in states where the right is preserved under state law.

Should the GOP gain control of the federal government in 2024, just as it had in 2016, it could pass a national ban on abortion that overrides even broad state protections. This is not some distant or academic threat; it is what GOP leaders are already telegraphing.

That means each and every House and Senate seat matters, and that a vote for the GOP anywhere is a vote against abortion rights and access everywhere. Democrats need to figure out how to make that both clear and urgent.

Whether Democrats will succeed in taking the state-level victory in Kansas and leveraging it into a successful national campaign remains to be seen. There are less than 100 days remaining to the midterm elections, and while momentum has been shifting, there is a lot of ground to make-up and continued unfavorable economic winds.

That said, Kansas showed us that what would have seemed impossible a week ago can in fact be done with the right messaging, the right energy, and the right amount of basic grassroots organizing.

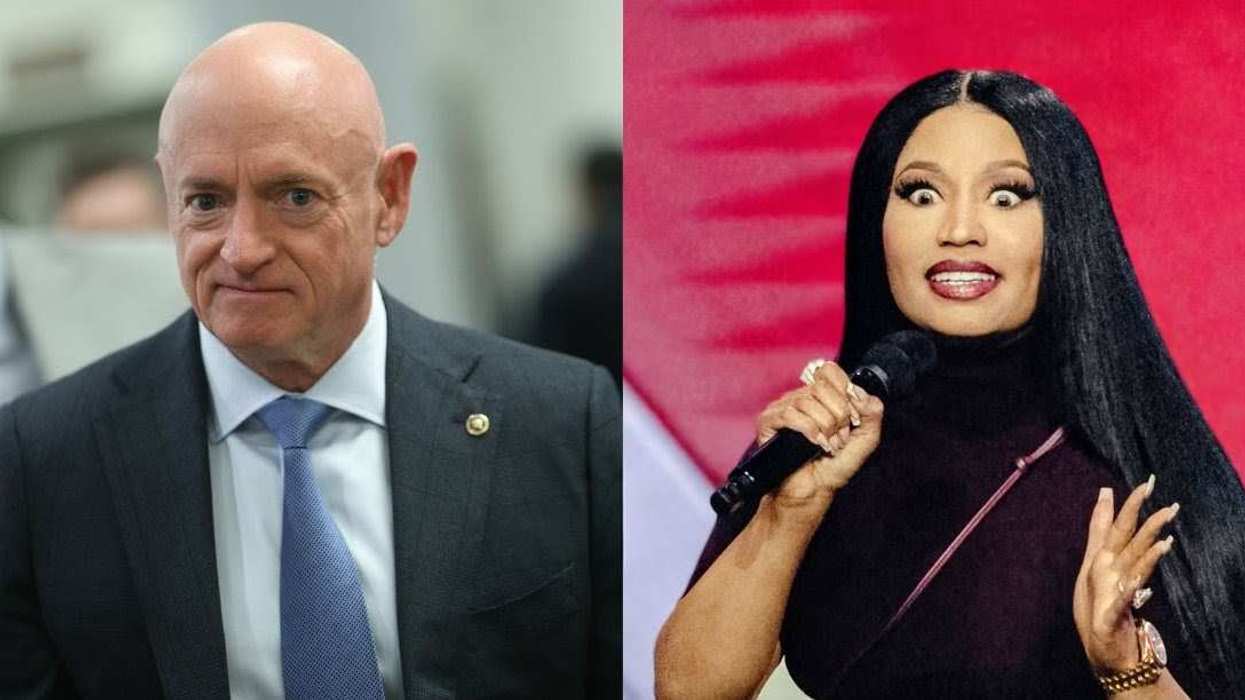

Roberto Schmidt/AFP via Getty Images

Roberto Schmidt/AFP via Getty Images

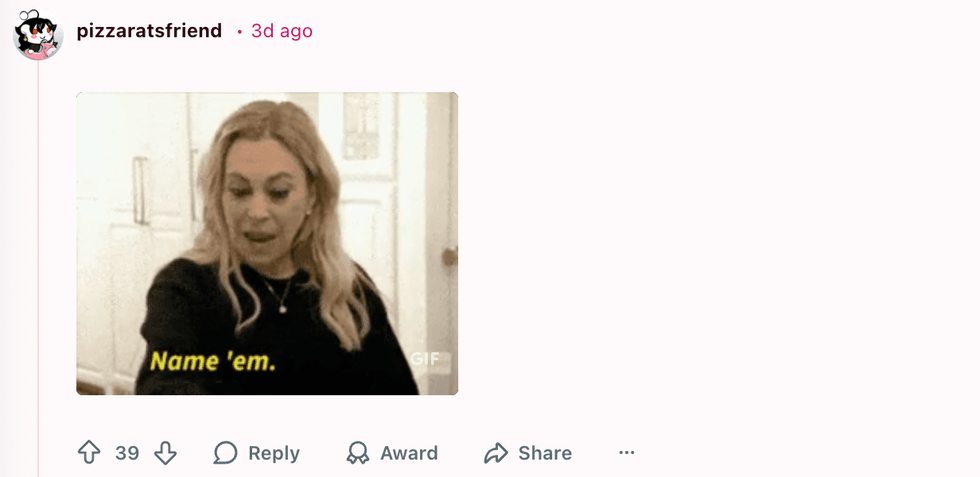

u/pizzaratsfriend/Reddit

u/pizzaratsfriend/Reddit u/Flat_Valuable650/Reddit

u/Flat_Valuable650/Reddit u/ReadyCauliflower8/Reddit

u/ReadyCauliflower8/Reddit u/RealBettyWhite69/Reddit

u/RealBettyWhite69/Reddit u/invisibleshadowalker/Reddit

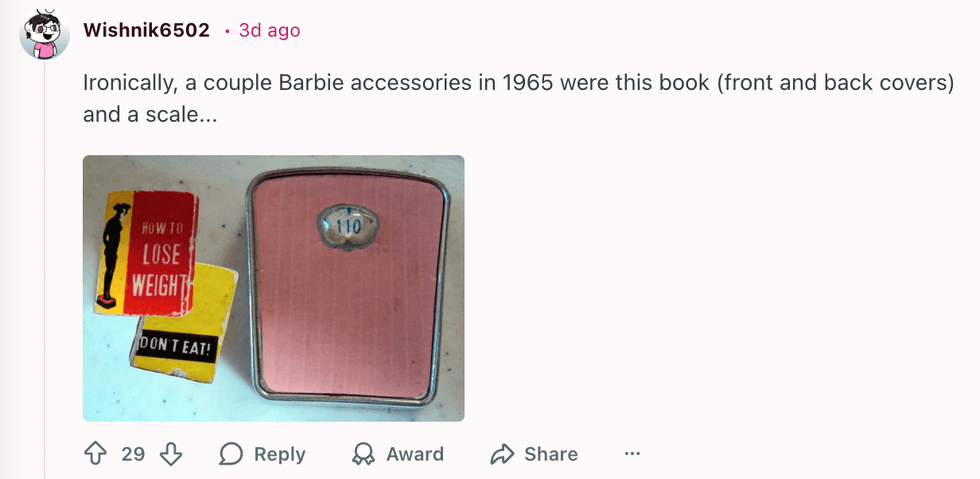

u/invisibleshadowalker/Reddit u/Wishnik6502/Reddit

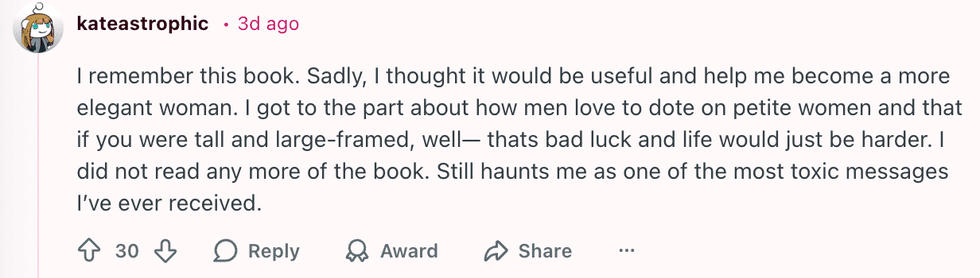

u/Wishnik6502/Reddit u/kateastrophic/Reddit

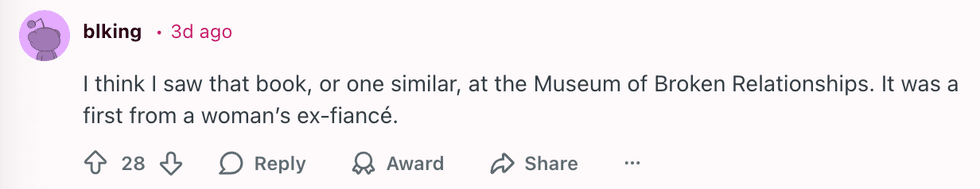

u/kateastrophic/Reddit u/blking/Reddit

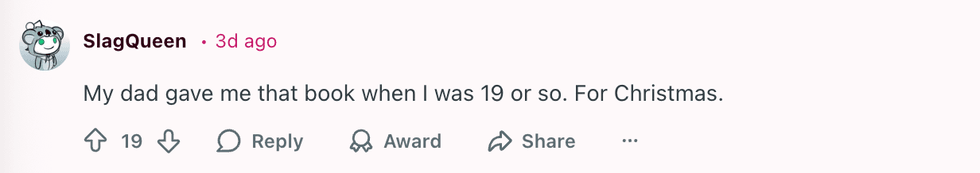

u/blking/Reddit u/SlagQueen/Reddit

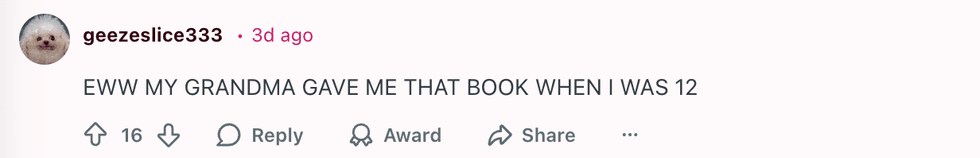

u/SlagQueen/Reddit u/geezeslice333/Reddit

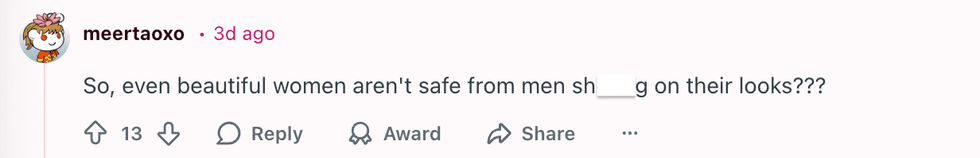

u/geezeslice333/Reddit u/meertaoxo/Reddit

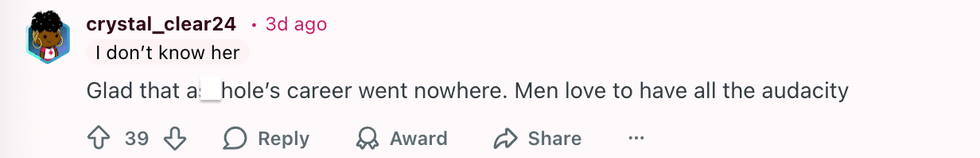

u/meertaoxo/Reddit u/crystal_clear24/Reddit

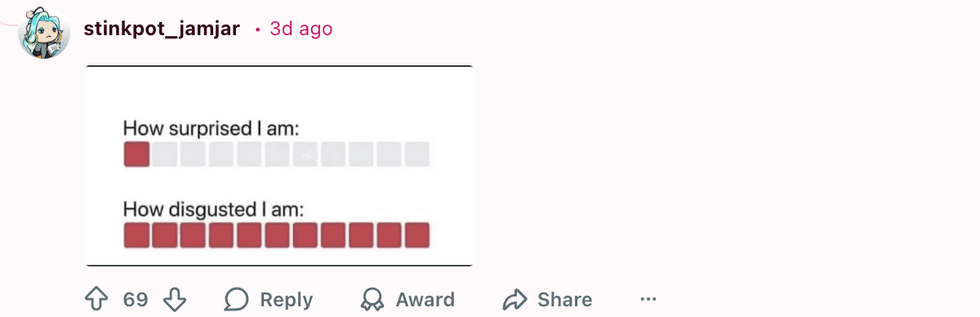

u/crystal_clear24/Reddit u/stinkpot_jamjar/Reddit

u/stinkpot_jamjar/Reddit

u/Bulgingpants/Reddit

u/Bulgingpants/Reddit

@hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok

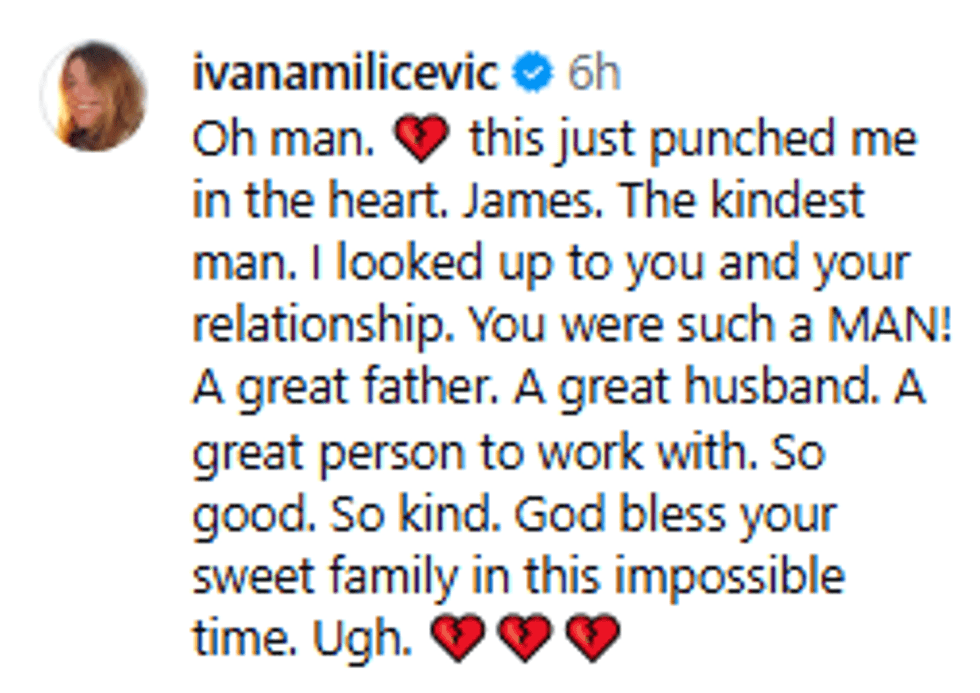

@vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram