In what’s being hailed as a world first in regenerative medicine, five children have received new ears grown from their own cells.

The children, living in China and ranging from age 6 to 10, were all born with microtia, a birth defect where at least one ear is underdeveloped. Traditional treatments for the condition involve either surgically attaching a synthetic ear or forming an ear from cartilage harvested from the patient’s ribs.

Now, however, new ears could be grown from a 3D-printed mold, somewhat similar to a process announced last year that created 3D-printed ovaries for infertile women.

“It’s a very exciting approach,” Tessa Hadlock at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary in Boston told New Scientist. “They’ve shown that it is possible to get close to restoring the ear structure.”

The technique, devised by researchers at Jiao Tong University in Shanghai and published last month in the journal EBioMedicine, involves creating a biodegradable 3D mold of the child’s unaffected ear. The patient’s own cartilage cells are then inserted into tiny holes that cover the mold; over the course of about 12 weeks, the cartilage cells begin to grow in the mold’s shape, as the mold breaks down. The ear can then be transplanted onto the patient.

Scientists plan to monitor the transplant recipients for the next five years, but so far none of the lab-grown ears has been rejected. The first patient to undergo the process has now successfully had her new ear for 2 1/2 years.

The process was inspired in part by the Vacanti Mouse, or “earmouse” of the 1990s — a hairless lab mouse with what appeared to be a human ear growing on its back. The image, often distributed via email or on the Internet without proper context, was most closely associated with the furor over genetic engineering.

However, the mouse contained no human cells. The ear, part of a study by tissue researcher Charles Vacanti, was grown using cartilage cells from a cow’s knee, seeded to an ear-shaped scaffold in a way similar to the Jiao Tong University study (one of whose authors was also a co-author of the Valenti study). The ear was never transplanted onto a human, however, as scientists worried a human body would reject an ear made entirely out of bovine cells.

“The delivery of shaped cartilage for the reconstruction of microtia has been a goal of the tissue engineering community for more than two decades,” Lawrence Bonassar, a biomedical engineering professor at Cornell University, told CNN.

Microtia occurs in 1 out of every 5,000 births, and is more common in Hispanic, Asian and Native American populations. It can result in hearing impairment and/or the inability to wear glasses.

“This work clearly shows tissue engineering approaches for reconstruction of the ear and other cartilaginous tissues will become a clinical reality very soon,” Bonassar added. “The aesthetics of the tissue produced are on par with what can be expected of the best clinical procedures at the present time.”

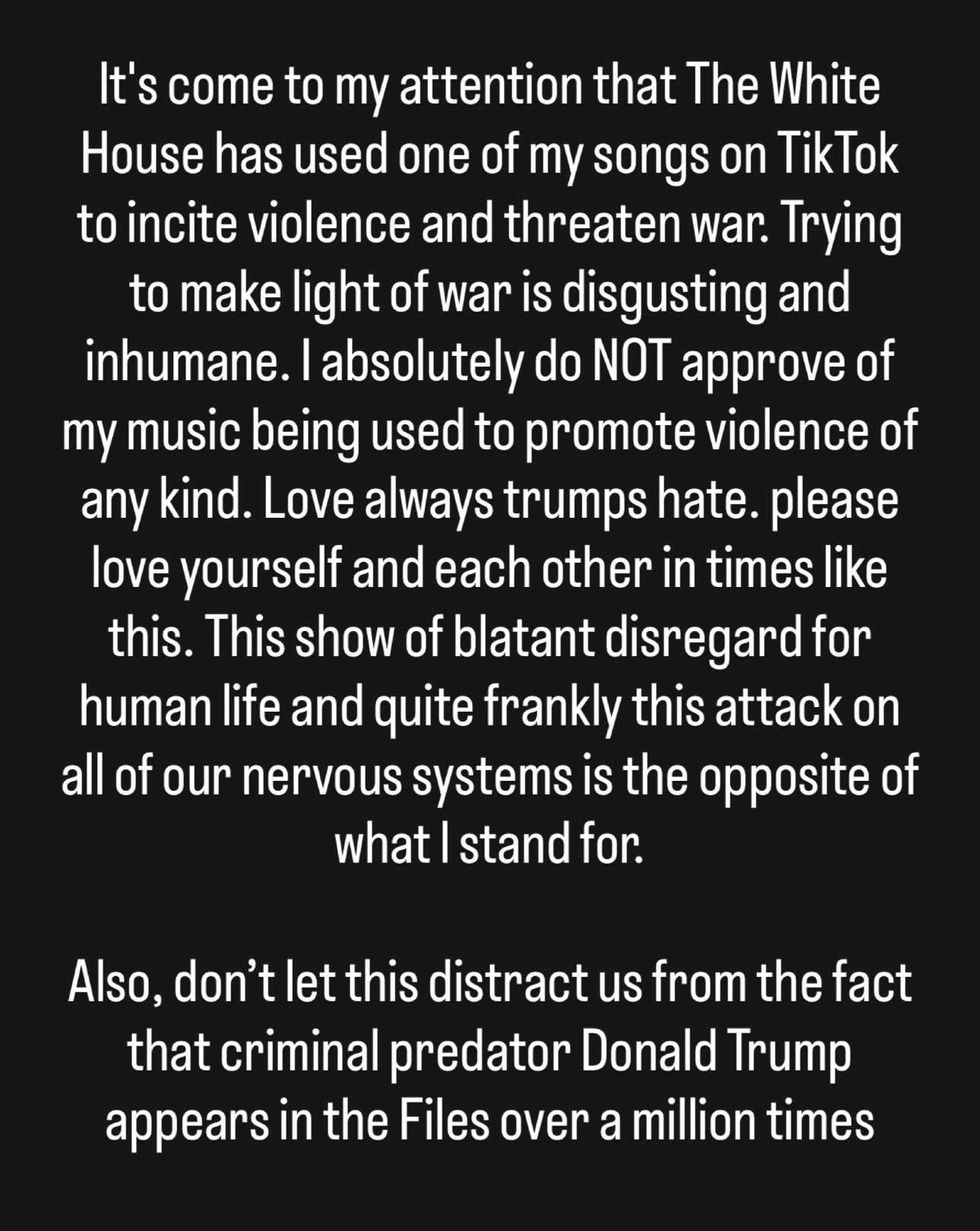

@KeshaRose/X

@KeshaRose/X