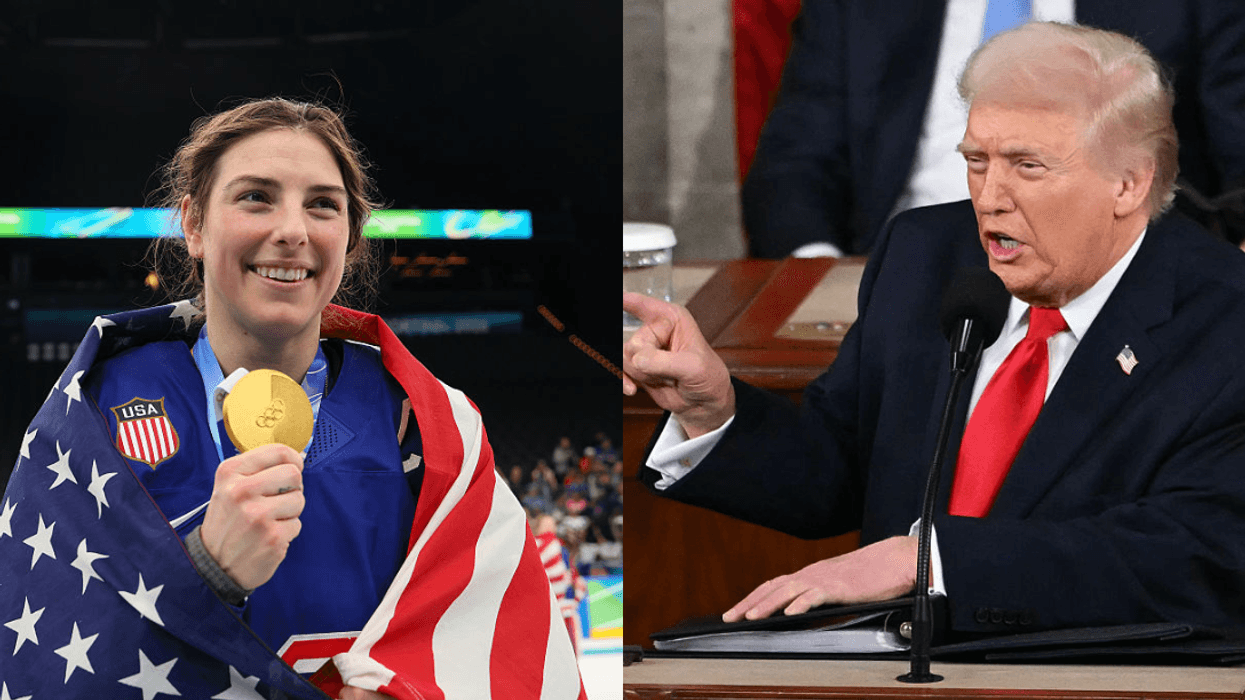

A year ago next month, President Donald Trump assured reporters on Air Force One that he never knew about the $135,000 in hush money paid to adult film actress Stormy Daniels in exchange for her silence ahead of the presidential election about their 2006 affair.

His answer that April is coming back to haunt him.

Trump is no longer denying he knew about a hush money payment his former attorney and fixer Michael Cohen made to adult film actress Stormy Daniels.

The president claimed the payment "was not a campaign contribution" and therefore does not constitute a campaign finance law violation.

Trump's statement comes scarcely more than a week after Cohen's testimony before the House Oversight and Reform Committee, in which he claimed Trump lied about the payment. He presented Congress with a copy of an August 2017 check for $35,000 that appears to be signed by Trump.

Cohen said the check was a partial reimbursement for the $130,000 he paid Daniels during the 2016 presidential campaign.

“I am providing a copy of a $35,000 check that President Trump personally signed from his personal bank account on August 1 of 2017 — when he was president of the United States — pursuant to the cover-up, which was the basis of my guilty plea, to reimburse me — the word used by Mr. Trump’s TV lawyer — for the illegal hush money I paid on his behalf,” Cohen said at the time. “This $35,000 check was one of 11 check installments that was paid throughout the year, while he was president.”

Trump was swiftly called out.

This isn't the first time the president has claimed he knew about the payments, however.

In August 2018, immediately after Cohen pleaded guilty to eight criminal counts––five charges of felony tax evasion, two counts of campaign finance violations, and one count of bank fraud––Trump sat down for an interview with "Fox and Friends" and changed the tune he'd previously struck on Air Force One.

The president claimed that he knew about payments Cohen made to silence Daniels and Playboy model Karen McDougal but insisted that these payments did not come from campaign coffers and thus do not constitute a campaign finance violation.

“Later on I knew, later on,” Trump told Fox’s Ainsley Earhardt. “But you have to understand Ainsley, what he [Cohen] did, and they weren’t taken out of campaign finance. That’s a big thing, that’s a much bigger thing, “Did they come out of the campaign?” and they didn’t come out of the campaign, they came from me, and I tweeted about it. I don’t know if you know but I tweeted about the payments.”

Insisting once again that the payments did not “come from the campaign,” the president said that “the first question” he asked when he heard about the payments was, “Did they come out of the campaign?”

“Because that could be a little dicey,” he added, “and they didn’t come out of the campaign and that’s big,” continuing: “But they weren’t––it’s not even a campaign violation. If you look at President [Barack] Obama, he had a massive campaign violation, but he had a different attorney general and they viewed it a lot differently.”

Trump’s statements indicate he misunderstands just why the payments themselves are so important. Cohen said that he made the payments at Trump’s behest to influence the election. In fact, as he pleaded guilty to the campaign finance violations, he said he had paid Daniels and McDougal hush money “in coordination and at the direction of a candidate for federal office… for the principal purpose of influencing the election.”

It does not matter whether the money to pay these women came from the campaign or not: That the women were paid off for the explicit purpose of boosting Trump’s chances of winning the 2016 presidential election is precisely why the scandal has received so much airtime, even as salacious details of Trump’s proclivities during his affairs with both Daniels and McDougal have also nabbed front page headlines.

Trump’s claim that former President Barack Obama is guilty of the same crime as Cohen also doesn’t hold up under scrutiny.

Trump referred to a $375,000 fine levied by the Federal Election Commission in early 2013 against Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign. The FEC said the Obama campaign missed filing deadlines for disclosing large donations during the final weeks of the campaign, reported the wrong dates on certain contributions, and did not return donations that exceeded the campaign contribution as quickly as they should have.

The violations amounted to “a small, technical paperwork error that people who were trying to get it right might make,” Epner said. “$375,000 for the FEC is a meaningful fine, but compared to the amounts that were involved it’s tiny.”

According to MitchellEpner, a former federal prosecutor who is now of counsel at Rottenberg Lipman Rich P.C., reoccurring donations can put a donor over the legal limit and campaigns are required to track donation totals and return excess amounts after 60 days. The Obama campaign did not do this in a timely manner, and an FEC audit found some donations which exceeded the legal limit (which were then subsequently refunded). The FEC’s conciliation agreement with the campaign notes this.

Eppner said that it’s “extremely implausible” that an attorney general could influence the regulation or prosecution of violation of campaign finance laws. Intent and motivation are important factors; the FEC concluded that the Obama campaign did not intend to commit federal crimes.

@CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram

Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images

Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images