While Flint’s water crisis has fallen out of the public news cycle, its residents are still living with the aftermath of an estimated 40 percent of homes that drank and bathed in dangerously lead-polluted water. It took several years, in which residents—including children—were turning up with mysterious rashes and other illnesses—before national attention to the crisis forced the city to admit it had a problem.

The city of Flint disconnected from Detroit’s water line as a cost-cutting measure and began to draw water from the Flint River in April 2014. Soon after, shockingly high levels of lead were found in the city's water supply.

At its worst point, a report of the tap water, done by scientists at Virginia Tech found that the lead level in Flint homes was as high as 13,200 parts per billion (ppb). To put that in perspective: Lead-contaminated water is classified as hazardous waste by the EPA at only 5,000 ppb.

Enter one 11-year-old girl with a mind for science, Gitanjali Rao. Though she lives in Lone Tree, Colorado, she was moved by the city’s plight, which she was introduced to in a school STEM lab, and through the news.

“I was appalled by the number of people affected by lead contamination in water and I wanted to do something to change this,” she told ABC.

Inspiration really struck after she watched her engineer parents test for lead in their own tap water, and decided to build a lead-detecting device that would be easy and affordable for anyone to use. She lit on a method during her weekly browse of the MIT Department of Materials Science and Engineering’s website. Inspired by carbon nanotubes that are sensitive enough to detect toxic gases in the air, she realized she might be able to use similar technology to create a lead-detecting test for water. The result won her $25,000 and the distinction as “America’s Top Young Scientist” in the Discovery Education 3M Young Scientist Challenge.

“When I saw my parents testing for lead in our water, I immediately realized that using test strips would take quite a few tries in order to get accurate results and I really wanted to do something to change this, not only for my parents but for the residents of Flint and places like Flint around the world,” she told Rookie Magazine.

Of course, getting her prototype required some tenacity and persistence on Rao’s part. ABC reported she “spent months trying to convince local high schools and colleges to give her lab time to continue her experiment.”

And at home, Gitanjali asked her parents to create a “science room” in their Colorado home for her to do just that.

Her father, Ram Rao, said, “We had to learn as she asked questions. Our first question was, ‘Is this what you really want to go after? Because it’s a sizable problem.’”

He added, “Then you go one day at a time. There was no real expectation that she would necessarily finish, but the journey itself would be the learning experience. It turned out she had a lot more determination.”

The young Rao’s device, which she named “Tethys,” after the Greek goddess of water, is an ingenious arrangement of the following components: a disposable cartridge that holds chemically treated carbon nanotubes, an signal processor using the coding language Arduino with a Bluetooth attachment, and it links up to a smartphone app that displays the results.

While it may seem unnecessary to create a new lead testing device, it turns out that testing for lead in the water is not as easy as it seems and can cost a lot of money and require multiple tests. As of 2016, lead-contaminated water is an issue for more than 5,300 water systems in the U.S., so Rao’s device could save a lot of time and money for both municipalities and residents.

Rao’s device relies upon the relatively new field of nanotechnology. In it, the carbon nanotube cartridge is extremely sensitive to any changes in electron flow. The nanotubes are then lined with atoms that are attracted to lead, which adds resistance as the electrons flow through, which can be measured.

When you put the cartridge in clean water, there’s no change in the electron flow and the smartphone app will show that it’s all clear to drink (or bathe) in that water. But if the water is contaminated with lead, the water will react to the atoms, creating that resistance, or slowing, in the electron flow that the Arduino processor will be able to measure. In this case, the app will show that the water is not safe to drink.

While the system sounds simple, it is quite a feat of engineering, especially for an 11-year-old.

But Rao showed herself to be more than up to the challenge, not only in her own invention, but throughout the judging process of the prize. During the final competition, all ten finalists had to present their inventions to a panel of 3M scientists, which included school superintendents and administrators from across the country. In addition to that, the finalists had to pair up and compete in two additional challenges that required combining multiple 3M technologies to solve real-world problems.

"It's not hyperbole to say she really blew us out of the water," Brian Barnhart, a school superintendent in Illinois and one of the 3M judges, told ABC. "The other nine kids, they were also such amazing kids, so for her to stand out the way she did with a peer group like this is like an exclamation point on top of it."

While Rao comes by her own skills honestly, it helps that her parents are also engineers, and that she has been given access to STEM classes and lab at school. But Rao still had to invest a great deal of time and experimentation to get her prototype to the point where she could win the prize.

Once Rao and nine others made it to the finalist round, they were paired with a scientist to help them take their idea from prototype to reality. Rao was paired with 3M scientist, Dr. Kathleen Shafer, whose focus is on developing new kinds of plastics.

Rao told Rookie, “Dr. Shafer helped me so much throughout this whole journey. She helped me a lot with my experimentation plans and making sure I wasn’t immediately rushing to the next steps.”

While she admits she was nervous at first to talk to “someone so knowledgeable and an accomplished scientist,” Shafer quickly put Rao at ease and taught her some valuable lessons.

“I learned to be diligent and persistent from Dr. Shafer. She always listened to my failures and provided me alternate paths to keep moving ahead. She taught me to reach out and ask for help. Before, I would hesitate to ask a question to someone whom I haven’t met before. But Dr. Shafer encouraged me to reach out to college professors and high school teachers for either space to perform my tests or to ask a question related to my research.”

Rao is younger than most scientists as they begin their careers, but she has no plans to stop. Her goal is "to save lives and make the world a better place."

While she will be using a lot of her prize money for college, she hopes to use some of it to invest in Tethys to make it commercially available.

And she already has some advice for other scientists who wish to follow in her footsteps: "Advice I would give to other kids would be to never be afraid to try," Gitanjali said. "I had so many failures when I was doing my tests. It was frustrating the first couple of times, but towards the end, everything started coming together."

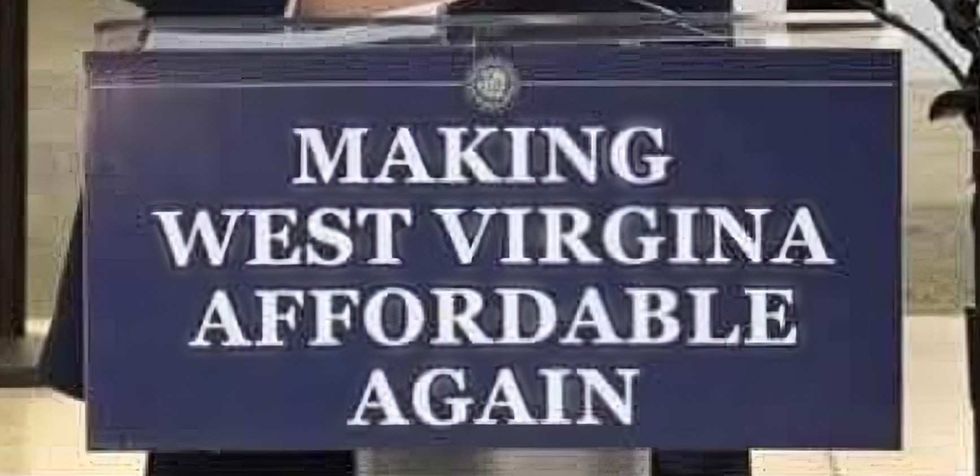

@ameliaknisely/X

@ameliaknisely/X WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook