President Donald J. Trump’s administration lives by a single overriding credo — if Barack Obama built it, they’ll tear it down.

Environmental activists have been watching as regulation after regulation and safeguard after safeguard gets thrown on the chopping block, essentially leaving Obama’s noteworthy environmental legacy in tatters — unless legal challenges to Trump policy prove successful in court.

To secure the vote of Alaska Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski for December’s large tax break for corporations and wealthy Americans, the U.S. Senate removed protections established by Obama that prevented drilling by oil companies in the pristine Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), which environmentalists deem sacred because it remains so unspoiled. It has also been home to Gwich‘in natives — an Athabaskan people — who continue to live traditionally, as they have for untold centuries.

No less a personage than Dr. Jane Goodall, the British primatologist who has become a household name because of her work with chimpanzees in Tanzania, entered the political fray just before the vote.

“If we violate the Arctic Refuge by extracting the oil beneath the land, this will have devastating impact for the Gwich‘in people for they depend on the caribou herds to sustain their traditional way of life,” wrote Goodall in a letter to American legislators.

Goodall believes that the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge’s “very wildness speaks to our deeply rooted spiritual connection to nature, a necessary element of human psyche.”

A History of Failure

Congress has tried to open up the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling 50 times before now, so this is a victory for oil companies, but not entirely unexpected. By passing this measure from within a far-reaching tax bill, Republicans are hiding the devil in the details.

All energy companies are rejoicing about having one of their own in the White House. The budget not only opened up the Arctic Refuge, but it cut 9 cents per barrel tax on all oil production to pay for inevitable oil spills. And then, just this month, Trump made offshore drilling legal again throughout the US, despite widespread condemnation from many states that rely heavily on tourism along their coasts.

Environmentalists have many battles to wage, but the fight to save the Arctic carries great import.

This unspeakably beautiful region is home to polar bears, caribou and millions of birds who migrate with changing seasons. When Obama designated an even larger swathe of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge as wilderness in 2015 — the highest level of protection given to public lands — it was believed that this area in Alaska would soon be cherished by all Americans in the same way that the Grand Canyon and Yosemite are considered natural works of art.

Ramifications for Alaska and the Planet

Other biologists and ecologists agree that this decision is a disaster. The Arctic Refuge is a prime breeding ground for many species, especially caribou relied upon by the Gwich‘in natives and for legions of migratory birds, according to Columbia University researcher Natalie Boelman.

It’s not just oil spills, Boelman says. The damage done by large trucks and heavy equipment leaves scars on the land that take generations to heal — if they manage to heal at all. Even noise and dust can be devastating to fragile species.

“In the spring, every pond or puddle is covered in ducks and geese,” Boelman says. “It’s loud. There are millions, billions of them that count on these areas for breeding habitats. The region is essentially one of the Earth’s most important bird nurseries.”

Some species are fragile or endangered, and might not survive a dramatic upheaval.

“Birds migrate there from all over the world,” Boelman adds. “If something happens to their breeding grounds, it will impact the rest of the planet.”

To be fair, not all of the Arctic Refuge is falling under the knife. The new plan will carve up the the coastal plain, which is about the size of South Carolina. Congress and Alaska Senator Murkowski don’t see fragile ecosystems when they look at the area, they see tax dollars. Now that Congress has ballooned the deficit by passing a $1.5 trillion tax break for the wealthy, the potential for $1.9 billion in tax revenue and possible economic spinoffs are too tempting to pass up. Notably, the Center for American Progress disputes that benefit, arguing that the real figure for tax revenues would be $37.5 million.

Drilling for Oil as Climate Change Bites

In many ways, it seems an odd decision for Alaska’s politicians. Climate change is hitting Alaska hard, with polar amplification ensuring that this northern state warms 2.5 times as fast as the continent. Rising temperatures on land and sea are affecting traditional industries like the salmon fishery, where small changes in freshwater acidification can wipe out breeding areas on rivers — which happened in eastern Canada through acid rain from the American rust belt.

Environmentalists are hoping that time is on their side. Drilling is unlikely to start tomorrow or anytime soon.

First, the Department of the Interior needs to divide up the area for leases and — after doing so — allow time for public comment. Lawsuits and legal challenges are already in the offing, potentially slowing even this first step.

As well, the area hasn’t been surveyed for its oil potential by the United States Geological Survey in more than 30 years. The equipment and methods used then indicated that between 4.3 to 11.8 billion barrels of oil might be present, but many oil companies would like more precise data using modern equipment and software to hedge their bets.

The price of oil is yet another factor. With modern technologies and renewables becoming the face of energy in the 21st century, demand for oil and gas is waning, despite the efforts of Congress to prop up failing industries.

Another very important consideration is optics. For many people of a certain age, the Alaskan oil spill caused by the Exxon Valdez marked their first forays into environmentalism. A pristine coastline was all but destroyed, and images of oil-coated birds drawing their last breath was a potent reminder of the damage humanity can do to the planet. Oil companies might be slow to bid for leases when oil from less biologically sensitive areas is available.

Certainly, with midterm elections on the horizon, and the Republican Party wildly unpopular, a lot can change. If the Democrats controlled both the House and the Senate, they could slow development in Alaska, or impose a carbon tax that makes developing the region less appealing.

Certainly, the battle over the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is just beginning, and environmentalists are playing a long game. It will start with the courts, and move back to Congress and the presidency if, as seems likely, a blue tsunami changes the political dynamic after the midterms.

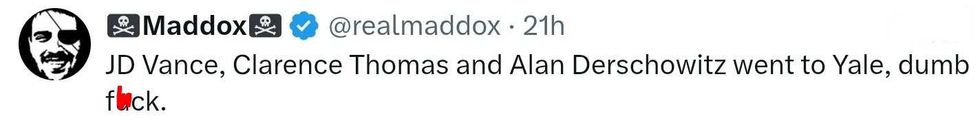

replying to @elonmusk/X

replying to @elonmusk/X replying to @elonmusk/X

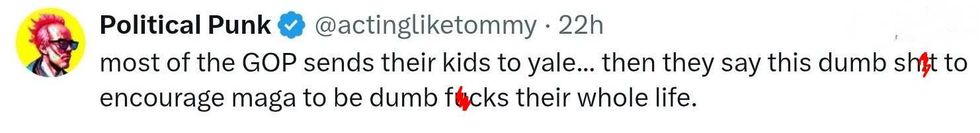

replying to @elonmusk/X replying to @elonmusk/X

replying to @elonmusk/X replying to @elonmusk/X

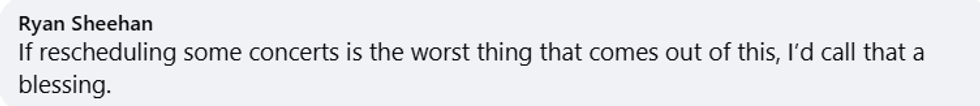

replying to @elonmusk/X

Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook