Early next month, Mississippi will elect a new governor—but it may not be the Mississippi public who elects him.

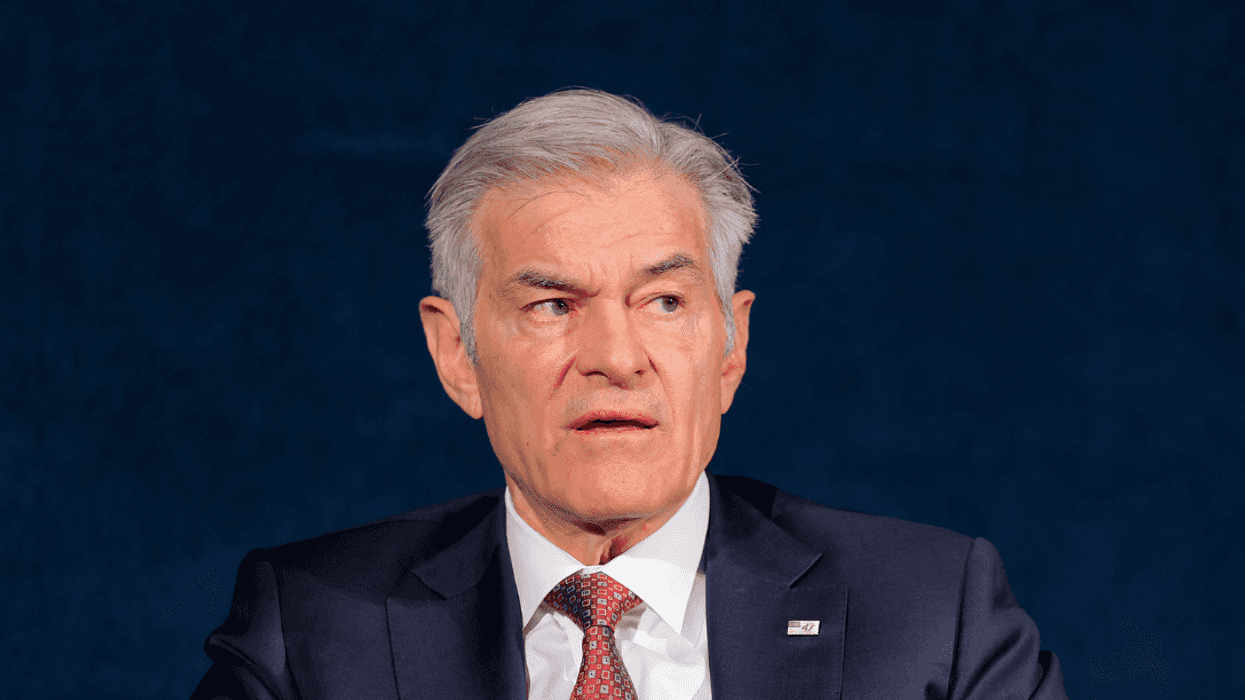

Republican Governor Phil Bryant is coming to the end of his second term, setting the stage for a showdown between current Republican Lieutenant Governor Tate Reeves and Democratic Attorney General Jim Hood.

However, an obscure 1890 provision in the state's post-Reconstruction Constitution may pose a problem to the legitimacy of the election results.

Ratified during the Jim Crow era, which saw African Americans in Mississippi greatly disenfranchised and subject to rampant racist violence, the state Constitution mandates that even if a gubernatorial candidate achieves a majority of the statewide vote, he or she must also win a majority of Mississippi's 122 congressional districts. If the standard isn't met, the decision could be left to the Republican-dominated House of Representatives.

Though Mississippi has the second highest Black population in the Union at 38%, only 42 of its Congressional districts are majority-black—20 districts short of a majority.

Scholars say the 1890 provision was adopted for the express purpose of nullifying the Black vote, since—due to the prevalence of slavery in the Antebellum era—Mississippi still had one of the highest African American populations in the country at the time of its ratification.

Echoes of widespread voter suppression from the Jim Crow Era, like that of this provision, continue to suppress Black voters.

Now, four Black Mississippians are determined to change that.

The longtime voters—two of whom were subject to poll taxes and three of whom were made to take tests before they could register to vote—have filed a complaint to strike down the provision.

The complaint states:

“The Popular-Vote Rule ensures that even when African-American-preferred candidates generate enough support to win a plurality of votes, they are unlikely to be elected.”

The case, McLemore v. Hosemann, will be heard by a federal Judge in the capital city of Jackson—a Civil Rights-era battleground in which the state's recently-opened Civil Rights museum resides.

Many feel that the repeal of the provision is long overdue.

Republicans representing the defendants admit that the provision was founded on white supremacist efforts, but that but assert that the plaintiffs are claiming discrimination based on their political party, not racial discrimination.

The case began oral arguments on Friday morning.

@TweetforAnnaNAFO/X

@TweetforAnnaNAFO/X

Steve Urkel Oops GIF

Steve Urkel Oops GIF  Moon Walk Dance GIF

Moon Walk Dance GIF  The Office Monday GIF by 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment

The Office Monday GIF by 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment