More bad news for firefighters and their supporters.

As if increased cancer risk, throttled internet service and lack of benefits for prisoners on the front lines of this summer’s California wildfires weren’t devastating enough, a recent study has found that more firefighters are committing suicide than dying in the line of duty.

In 2017, a report by the Ruderman Family Foundation found that 103 firefighters committed suicide while 93 died while on the job. Further, the Firefighter Behavioral Health Alliance believes that only 40 percent of firefighter suicides are formally reported, which means the suicide rate could actually be twice the rate of dying in or from a fire-related cause.

“It’s really shocking,” said Miriam Heyman, one of the report co-authors, told USA Today, “and part of what’s interesting is that line-of-duty deaths are covered so widely by the press but suicides are not, and it’s because of the level of secrecy around these deaths, which really shows the stigmas.”

The Ruderman Family Foundation is a Jewish philanthropic organization that focuses primarily on promoting the rights of people with disabilities.

“First responders are heroes who run towards danger every day in order to save the lives of others,” said Jay Ruderman, Ruderman Family Foundation president, in a release. “They are also human beings, and their work exerts a toll on their mental health.

That toll can include not only the physical demands of the job, disturbing sights as a first responder to accidents and medical events, and frequent near-death experiences, but full 24-hour shifts and sleep deprivation, as well as a feeling of a loss of utility and identity upon retirement. In a 2015 survey, the Journal of Emergency Medical Services found 37 percent of firefighters had contemplated suicide, and 7 percent had attempted it — more than 10 times the civilian rate. However, an estimated 5 percent or fewer of fire stations provide mental health support.

Heyman argues this is not only a problem for firefighters and their families, but could be a safety issue for the public at large.

“These individuals are the guardians for our community,” she said. “What happens when their decision-making is flawed? We need for them to be healthy.”

The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, or Cal Fire, is one of the few departments that does offer mental health services for its employees. However, the stigma associated with asking for help is so great that Deputy Chief Mike Ming, who leads Cal Fire's employee support services, makes sure to drive an unmarked vehicle, not wear his uniform and convene somewhere neutral such as a coffee shop when meeting with employees who may need assistance. Even then, firefighters are often resistant to discuss their feelings.

“It comes from a history of a suck-it-up attitude, because that’s just what we do,” Ming said in an interview with Vice. “We’re not awesome at tapping into emotions, and we can store a whole career’s worth.”

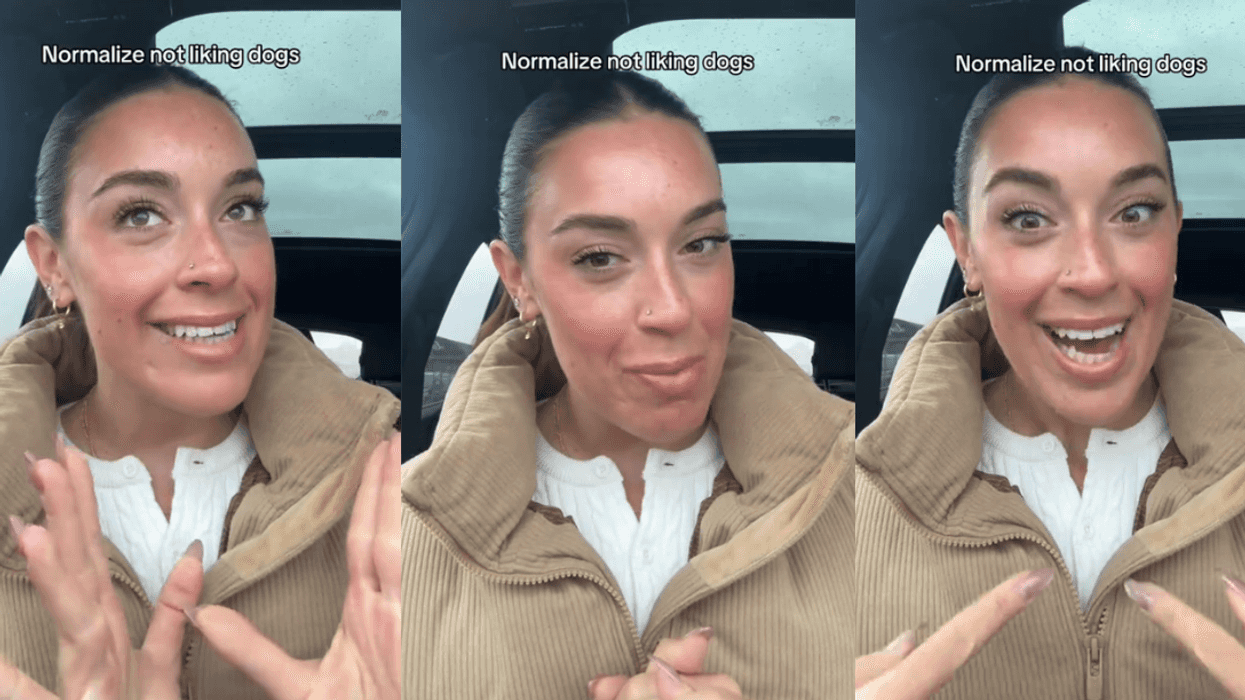

@madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok

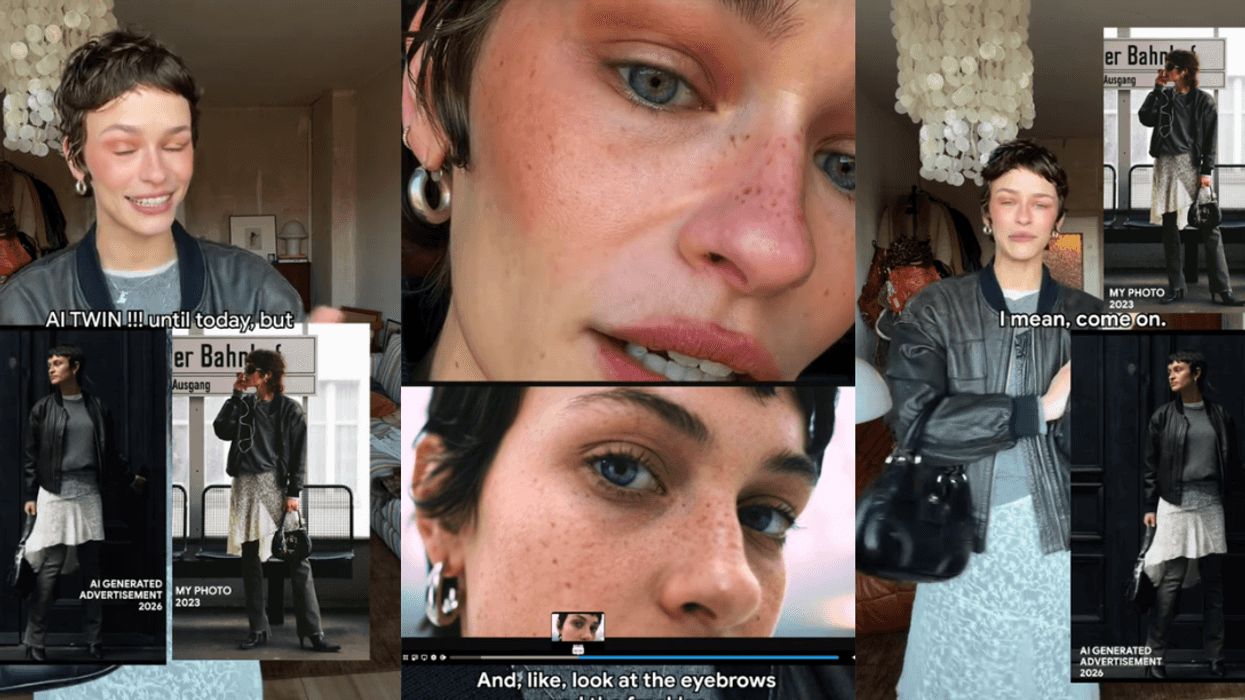

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok