In the wake of numerous mass shootings of 2017 and the growing cultural divide in the United States, one study sought to understand the meaning behind guns to their owners. Researchers discovered white men often see guns as a mechanism of empowerment when confronted with economic plight. This subgroup of gun owners tends to carry a particular set of values and policy positions, including insurrectionist tendencies, worth further study.

White men with financial concerns feel empowered by guns

F. Carson Mencken and Paul Froese, professors of sociology from Baylor University, published their study “Gun Culture in Action,” in the journal Social Problems. They used data from the Baylor Religion Survey 2014, to create a “gun empowerment scale.” Through survey questions surrounding gun owners’ feelings about guns, Mencken and Froese sought to assess their emotional and moral attachments to firearms.

Out of the total 1572 people surveyed from the continental United States in a Gallup Poll, 577 owned guns. Data indicates the average gun owner is more likely to be a white male. Those scoring highest on the gun empowerment scale were 78 percent white and 65 percent male.

Froese, however, was most fascinated by the statistic surrounding economic status:

“But what was really interesting—and I think this speaks to something much larger than just a gun issue—was that it was white men who had felt some kind of economic setback who were most attached to their guns,” he said in an interview with Scientific American. “That suggests to me that there’s something cultural happening. We have white men who have expectations about what it means to be a white man in America today that are not being met.”

Froese further explained that “Economic realities are changing in the United States and there’s this whole population of working-class white men who feel embittered, in the sense that maybe they don’t feel as economically successful or as powerful in their communities as they think they should be.”

According to the study, women and people of color who suffer economic setbacks are finding empowerment somewhere other than weapons––“if they are finding it at all,” Froese said. Generally, people expressed equal levels of economic distress––regardless of whether they owned a gun––lacking job security, predictability, material or psychological welfare.

Because the men who ranked “most empowered” by guns were most often white and reported feeling they were in a financially unstable situation, the study concludes that guns serve to mitigate this group’s economic hardship.

Sense of Empowerment Extends Beyond Self-Protection

For these white men scoring high on the empowerment scale, the ripple effects of gun ownership extend far beyond a strong sense of self-preservation or protection against criminal activity.

The authors explained, “that economic distress enhances the extent to which white men, specifically, come to rely on the semiotic power of a cultural symbol.” The gun, serving as that symbol, provides them a source of power and identity. Moreover, Froese and Mencken conclude that these weapons have become a symbol through which white men are seeking a “nostalgic sense of masculinity.”

To put this in a larger context, Froese explained: “We had this group of white men in the U.S. who were benefiting from hierarchies of power and economic inequalities that gave them a real sense of self and purpose, and so when they lost that—or they perceived that they were losing that—they searched for other ways of feeling masculine, and the gun was a natural thing to drift towards.”

According to Mencken, the results demonstrate that as the economy grows more global, some people found a sense of restorative power and control in guns. They find purpose in their ability to protect their property, family and community.

Gun empowerment motivates some people beyond simple protection of self and others. Those in the highest group are most likely to state that violence against the US government is sometimes justified, while also declaring themselves the most patriotic. The data shows 74 percent of the highest empowerment group owned handguns for protection, and almost half of that same group also felt violence against the government might be required. That represents a 40 percent increase from the next highest empowerment group.

According to Froese, "This speaks to the belief in some 'dark state' within the government which needs fighting." He added, "What's paradoxical is that white male gun owners in the U.S. see themselves as hyper-patriotic, but they are the first to say, 'If the government impedes me, I have the moral and almost patriotic right to fight back.'"

Non-white males and females are much less likely to resort to violence against the government, despite intense feelings of economic strain. Froese hypothesizes on the difference in those tendencies.

"Perhaps it is because [non-white males and females] have always had economic anxiety but have developed different coping mechanisms," he said.

Froese told Scientific American: “Again, our findings speak to something even deeper than the gun issue—and that is that amongst white men who are feeling economically embattled, they are searching for narratives to explain their experiences. Some of the narratives that they are attracted to are narratives of embattlement—the idea that there are forces out there that are trying to undermine them.”

“Much of conservative media says that the government is always out to get you—out to take away your guns and your money—and so these kinds of narratives all feed together.” He added: “What’s so fascinating is that you have a group of Americans—again, namely white males—who proclaim that they’re patriots. And, in fact, they say that their gun ownership makes them feel extremely patriotic. But they’re the group that’s most likely to say that it’s okay to take up arms against the government.”

These conclusions line up with an ethnography by anthropologist Jennifer Carlson, as detailed in her 2015 book, Citizen Protectors. While studying Michigan residents who carried concealed guns, she discovered male residents found a sense of patriarchal purpose in the economically depressed community.

Similar to the “Gun Culture in Action Study,” Carlson indicates these conditions are only likely to arise in the context of “changing economic opportunities that have eroded men’s access to secure, stable employment.” When this occurs, Carlson wrote, “guns are used by men to navigate a sense of social precariousness.” In other words, men place themselves in the position of community protectors when the government, employers, and other sources of security feel uncertain or inadequate.

Likewise, Froese and Mencken’s study shows economically distressed white males find emotional and moral reassurance in guns, leading to the "frontier gun" symbolism of freedom, heroism, power, and community preservation.

Both studies indicate a specific group of gun owners who possess distinguishing characteristics. But this subset comes from a larger group that is not simple to identify in everyday life.

Overall, gun owners tend to be older, white, married, conservative, and from rural areas with a tendency toward social isolation. But the study shows gun owners report higher incomes, while the levels of education and happiness remain steady between the two groups. However, between the empowerment groups, levels of education tend to correlate lower for those with stronger attachments to their guns.

The characteristics of those who score high on the empowerment scale are far more complex than the average gun owner—particularly regarding religion, Froese explained.

How Religion Affects Gun Culture

While there is a relationship between religion and gun culture, it’s not what you might guess. In fact, there’s a negative correlation between highly religious people and those who feel particularly empowered by their guns. For these purposes, “highly religious” means attending church more than once a month. White men with loose affiliations to religious communities show the deepest connection to their guns.

As Froese explained, “Gun owners who are highly attached to a religious community are less likely to feel empowered by their weaponry. This suggests that the white men who are really attached to their guns are using guns as a substitute for other cultural sources of meaning and identity.”

Put another way, the authors suggest that perhaps “religious commitment offsets the need for meaning and identity through gun ownership.” Instead of focusing their attention on religious practice, "[t]he gun becomes their central sacred object," Froese said.

Empowerment Study Highlights Important Nuances of Gun Culture

Froese emphasized the distinct nature of this subgroup which is deeply empowered by gun ownership. Beyond religion, he explained that simple political affiliation is not enough to understand or predict the belief system of who will feel empowered by their gun ownership.

"Americans' attachment to guns is not explained by religious or political cultures," he says. “And the significance of political identity is too broad,” Froese explains. “It's not just money from gun manufacturers shaping gun legislation. It is the cultural solidarity and commitment of a sub-group of Americans who root their identity, morality and patriotism in gun ownership. This is gun culture in action."

By comparison, gun owners in the low to medium range of the empowerment scale are more likely to say they own guns as collector’s items, than use them for recreation or defense.

Study results showing people’s feelings about gun policy further demonstrate why gun culture is perpetuated in the US. While 90 percent of gun owners support expanded gun safety policy measures, there’s a strong correlation between those with strong empowerment scores and opposition to gun control—including mental health screening for gun purchases. Moreover, the strong empowerment group strenuously opposed banning handguns, semi-automatic weapons, and ammunition clips. They also more strongly supported concealed weapons and concealed carry permits, as well as measures to arm teachers.

As explained in the study, “These owners tend to view guns as a cure for gun violence rather than a cause.”

The authors find that “because a vocal and passionate minority of gun owners continues to feel emotionally and morally dependent on guns,” the continuing lack of regulation will prevail, despite loud opposition to the contrary. Indeed, white men were less likely to blame guns as a significant factor in violence and to condone insurrection.

Froese aimed to explain the most empowered group’s responses to policy questions, in light of the paradigms they exist within:

“People who were very high on the gun empowerment scale were the ones who had the most pro-gun gun policy attitudes. They were the ones most likely to say that arming the public will make them safer and arming teachers will make schools safer—so there is this kind of belief or faith in the ‘good guys with guns can solve a problem’ narrative.”

Froese added, “That narrative is not empirically supported, but at the same time it’s repeated and it clearly has a lot of believers. If your source of identity is gun ownership and you think it makes you a better member of your community, it would create some cognitive dissonance to turn around and say, ‘Well, actually, we need to make sure not many people have guns.’”

The study draws several practical conclusions about the group most empowered by guns, those gun owners’ relationship to gun culture, and why it matters.

“These findings indicate that a portion of gun owners who feel empowered by the gun form a distinct interest group—one that opposes gun control and feels that social problems and perhaps even personal troubles might be best solved by guns.” The study also finds that, “For this group, the gun and violence are the first order tools in the defense of individual freedom. In sum, gun empowerment matters because it is directly related to gun policy preferences.”

The authors further conclude that the data showing guns as a symbol of moral and existential empowerment demonstrates what is generating pro-gun and anti-government attitudes.

The study referenced the controversial statement made by then-candidate Barack Obama in 2008, saying: “In discussing the economic frustrations of rural Americans, President Obama famously said ‘[I]t's not surprising then that they get bitter, and they cling to guns or religion …’”

The authors called Obama’s use of the conjunction “or” between guns and religion “prescient” with respect to their findings that religion and guns are divergently correlated cultural symbols. The study also hypothesizes that “a finite number of [other] cultural symbols can stimulate an individual’s emotional devotion” in a more loving, positive way than guns—similar to religion.

Froese, who primarily researches religion, says, “I’m not particularly interested in gun policy itself but rather in how meaning and cultural symbols affect people’s understanding of the world, which in turn then makes us to better able to understand their actions.”

While much additional research would be required to understand the feelings and actions of gun owners fully, this study has initiated a more sophisticated, subtle conversation about gun culture and its various sub-groups.

Perhaps eventually, policymakers can understand enough about gun culture to better predict who is at risk to commit violent crimes and consider reducing their access to weapons. Of course, this is precisely what those empowered by their guns fear most.

@madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok

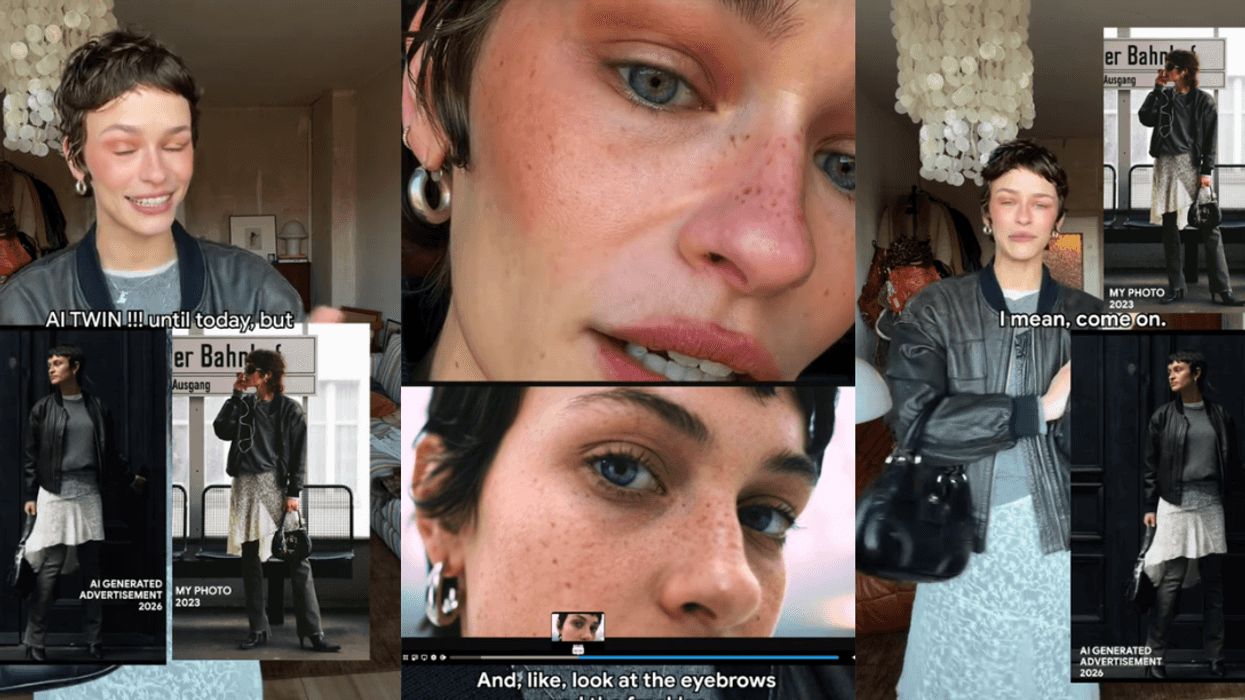

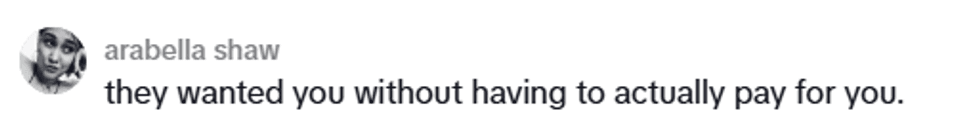

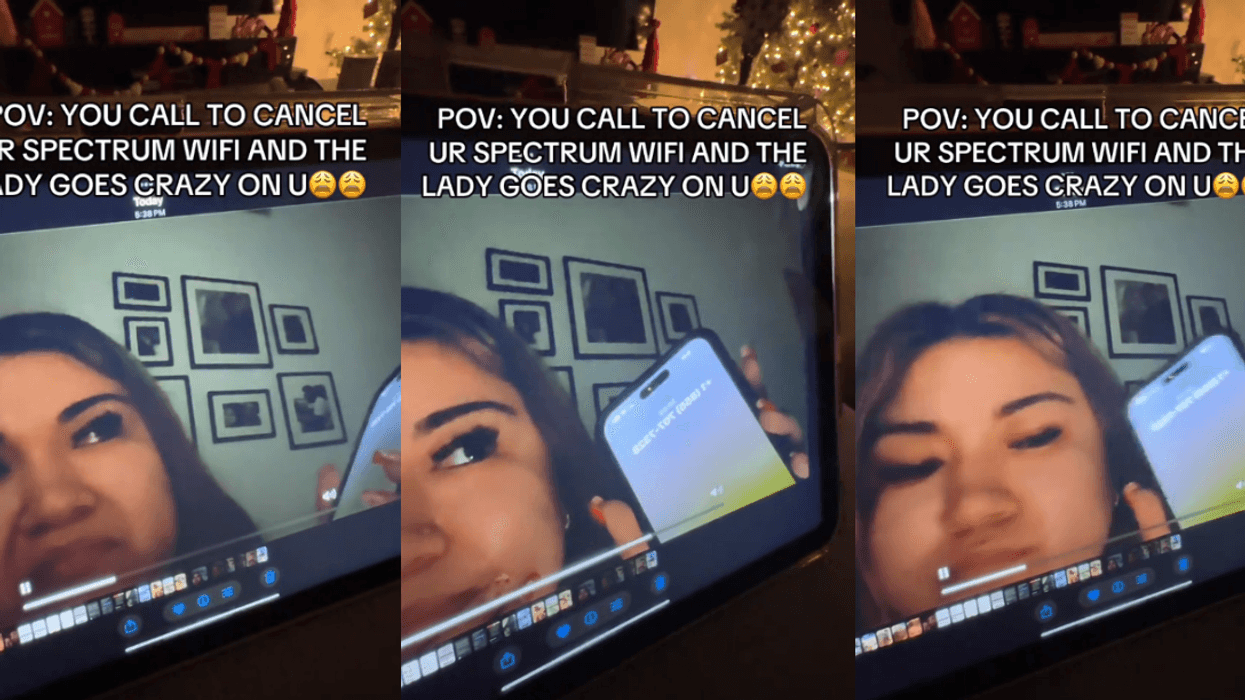

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

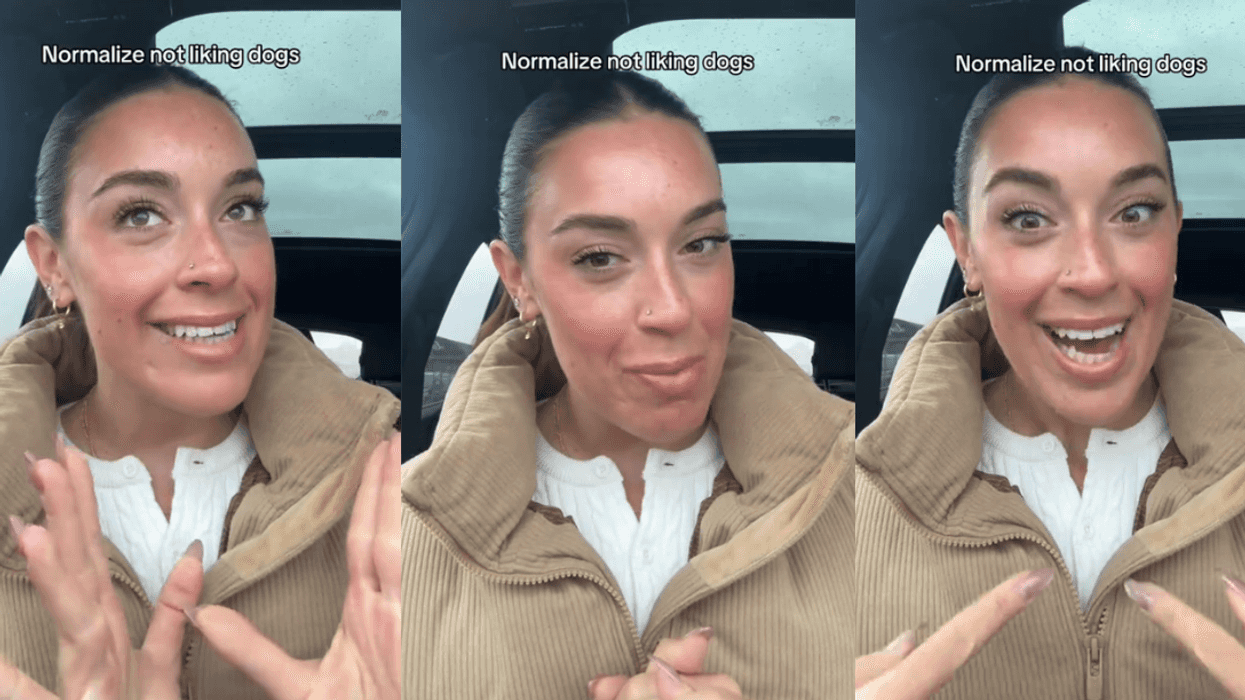

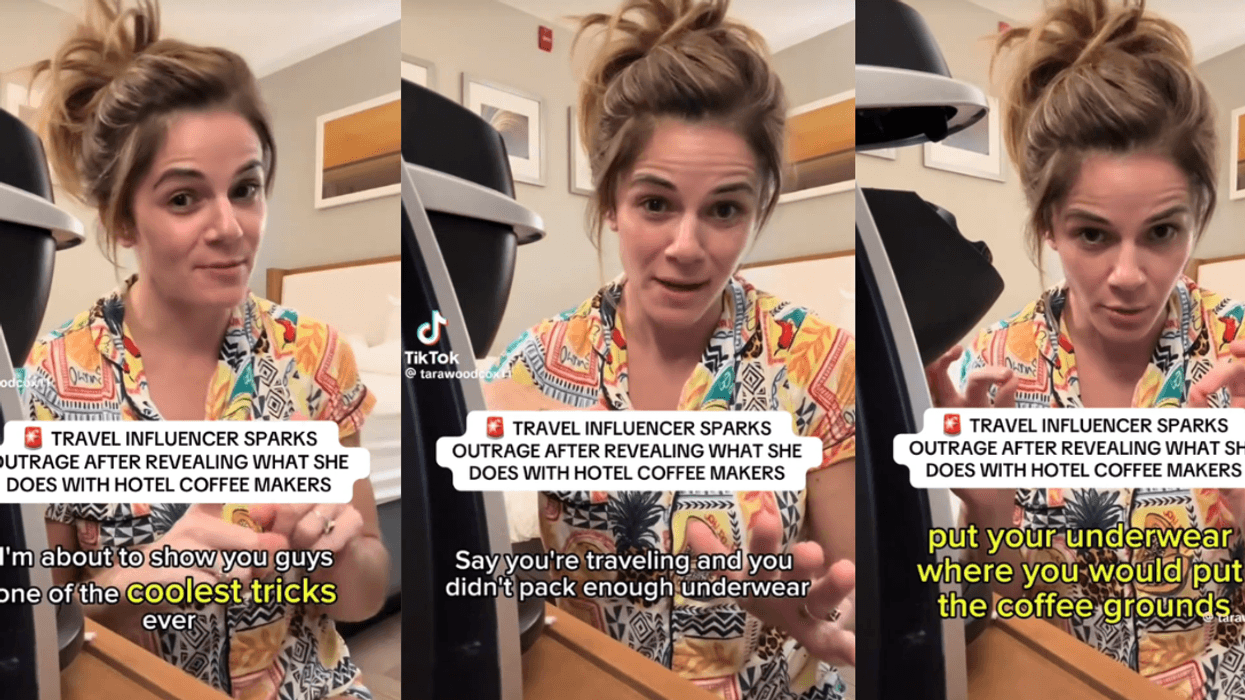

@anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok