Robin Camp, a Canadian Federal Court Justice, should be removed from the bench after he asked a 19-year-old rape survivor why she didn't do anything to protect herself during the alleged attack, according to the Canadian Judicial Council's committee of inquiry.

The case in question took place in 2014 after the young woman accused Alexander Wagar, of Calgary, of raping her over a bathroom sink at a house party. During Wagar's sexual assault trial, according to a notice of allegations posted on the Canadian Judicial Council website, Camp, who was a provincial court judge at the time, asked the young woman: "Why couldn't you just keep your knees together? Why didn't you just sink your bottom down into the basin so he couldn't penetrate you?"

According to the notice, the judge continued to castigate the young woman openly, suggesting that young women "want to have sex, particularly if they're drunk." In a different part of the trial, he said that "[Some] sex and pain sometimes go together...that's not necessarily a bad thing."

Camp would acquit Wagar in September 2014. "I want you to tell your friends, your male friends, that they have to be far more gentle with women," he told Wagar at the time. "They have to be far more patient. And they have to be very careful. To protect themselves, they have to be very careful." The Alberta Court of Appeal later overturned Camp's ruling. Wagar's second trial is underway. (Most recently, Pat Flynn, Wagar's defense, claimed that the woman accusing him of sexual assault had a case of "buyer's remorse.")

The Canadian Judicial Council launched an investigation in November 2015 after four law professors filed a joint complaint against Camp, who later recused himself from hearing sexual assault cases. The following month, the Alberta attorney general also filed a formal complaint and referred the case to the inquiry committee.

On Tuesday, the committee of inquiry concluded that, throughout the trial, "Justice Camp made comments or asked questions evidencing an antipathy towards laws designed to protect vulnerable witnesses, promote equality, and bring integrity to sexual assault trials." According to the committee's 116-page report, Camp "relied on discredited myths and stereotypes about women and victim blaming during the trial and in his reasons for judgment." The committee determined that Camp's misconduct placed him in a position "incompatible with the due execution of the office of judge."

The woman who survived the attack, whose identity is protected by a publication ban, was the first to testify at the inquiry, telling the committee that the judge's comments "made me hate myself" and that Camp "made me feel like I should have done something, like I was some kind of slut."

At a hearing in September, Camp, who grew up in South Africa, claimed he had a "nonexistent" knowledge of Canadian criminal law at the time of the trial. "My colleagues knew my knowledge of Canadian law was very minimal..." he said. "Please remember I wasn't in this country

through the 1960s, '70s and '80s." Records indicate Camp did not receive training or judicial education on sexual assault law before presiding over sexual assault cases.

Camp's attorney, Frank Addario, argued Camp is remorseful, and that he has since taken steps "to educate himself and gain insight into his beliefs." Addario conceded that Camp's remarks were "insensitive and inappropriate," but that he has since apologized, insisting Camp's misconduct does not warrant removal from the bench. Camp has openly acknowledged his "knowledge deficit" Addario said. According to a statement of facts, Camp has undergone mentoring, counseling about how victims of abuse respond to trauma, and a course on the history of sexual assault law.

In a letter of support, Camp's daughter, Lauren, who admitted she has been raped herself, said that her father's comments were "disgraceful" but indicated that she would stand behind him. Lauren Camp revealed her father is "old fashioned in some ways" and that he does not understand "how women think" but insisted he is not "an inherent or dedicated sexist." She also wrote that she had seen her father "advance in understanding and empathy for victims, vulnerable litigants and those who have experienced trauma."

But the inquiry committee––composed of three Superior Court judges and two senior lawyers––was unconvinced. Camp's apologies and efforts to educate himself on sexual assault law, they concluded, were not enough to justify keeping him on the bench: "We conclude that Justice Camp's conduct in the … trial was so manifestly and profoundly destructive of the concept of the impartiality, integrity and independence of the judicial role that public confidence is sufficiently undermined to render the judge incapable of executing the judicial office," the committee wrote.

Alberta Justice Minister Kathleen Ganley, who initially asked the Canadian Judicial Council to convene the inquiry, released a statement saying the committee's recommendation is "an important step forward to reinforce the way our courts should approach sexual assault cases."

“Asking for an inquiry was not a decision I took lightly. On reviewing the transcripts, I thought it was important that victims know this was not an acceptable way for any victim to be treated by the justice system," she said. “The decision for a victim of sexual assault to come forward can be very challenging and it is crucial that they know they will be treated with respect and dignity and not subjected to sexual myths and stereotypes."

Kim Stanton, legal director with the Women's Legal Education and Action Fund, which had intervener status at the inquiry, also praised the committee's decision. "It sends a very strong message to other judges and legal actors but also to survivors, that this kind of conduct is completely unacceptable in a Canadian court," she said. "It's a really important message that's being sent and there's absolutely no doubt in my mind that other judges will be taking acute notice of this decision."

Alice Woolley, a University of Calgary law professor who was among the first to file a complaint about the way Camp handled the sexual assault trial, said the committee's unanimous recommendation is a sign that the justice system is serious about correcting errors when they arise. "We're not always going to get it right. There will sometimes be terrible mistakes that happen," she said. "But our justice system curves toward justice in the end, and I think that's what this shows."

According to Norman Sabourin, the Canadian Judicial Council's executive director, Camp has 30 days to submit a written submission to the council in response to the committee's recommendation. The Judicial Council will then refer its recommendation to the minister of justice, who will make the final decision.

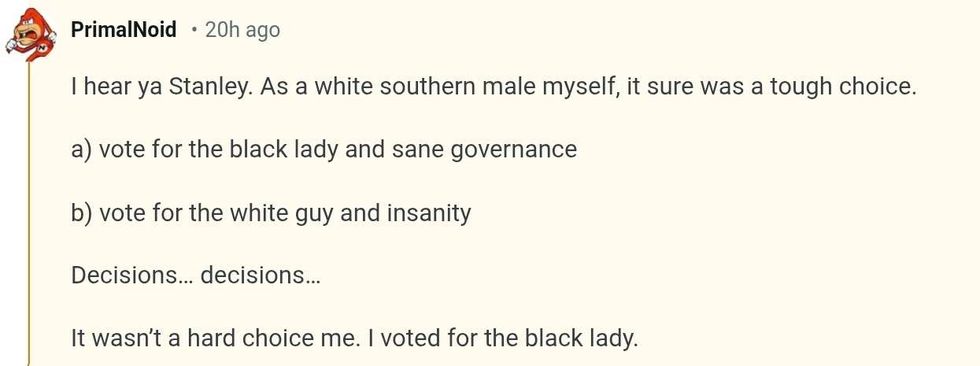

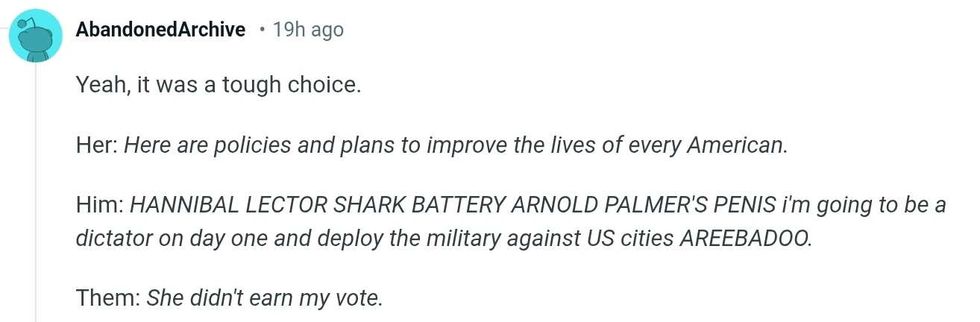

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

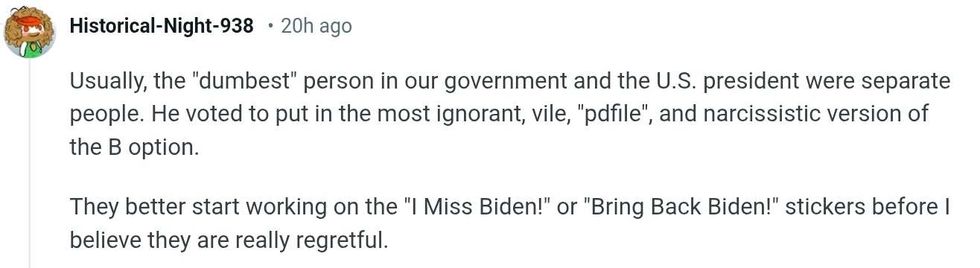

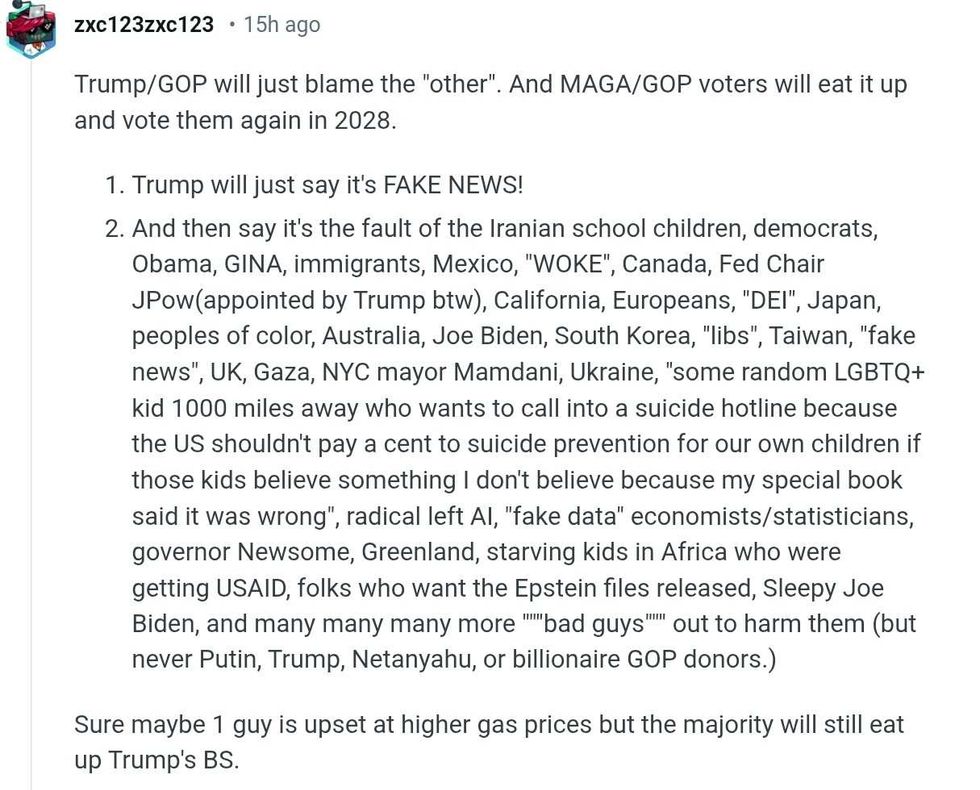

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

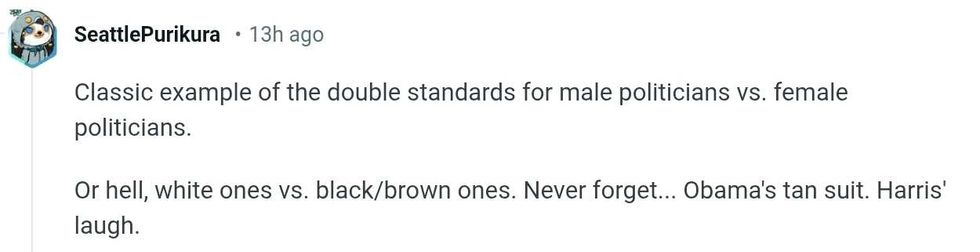

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

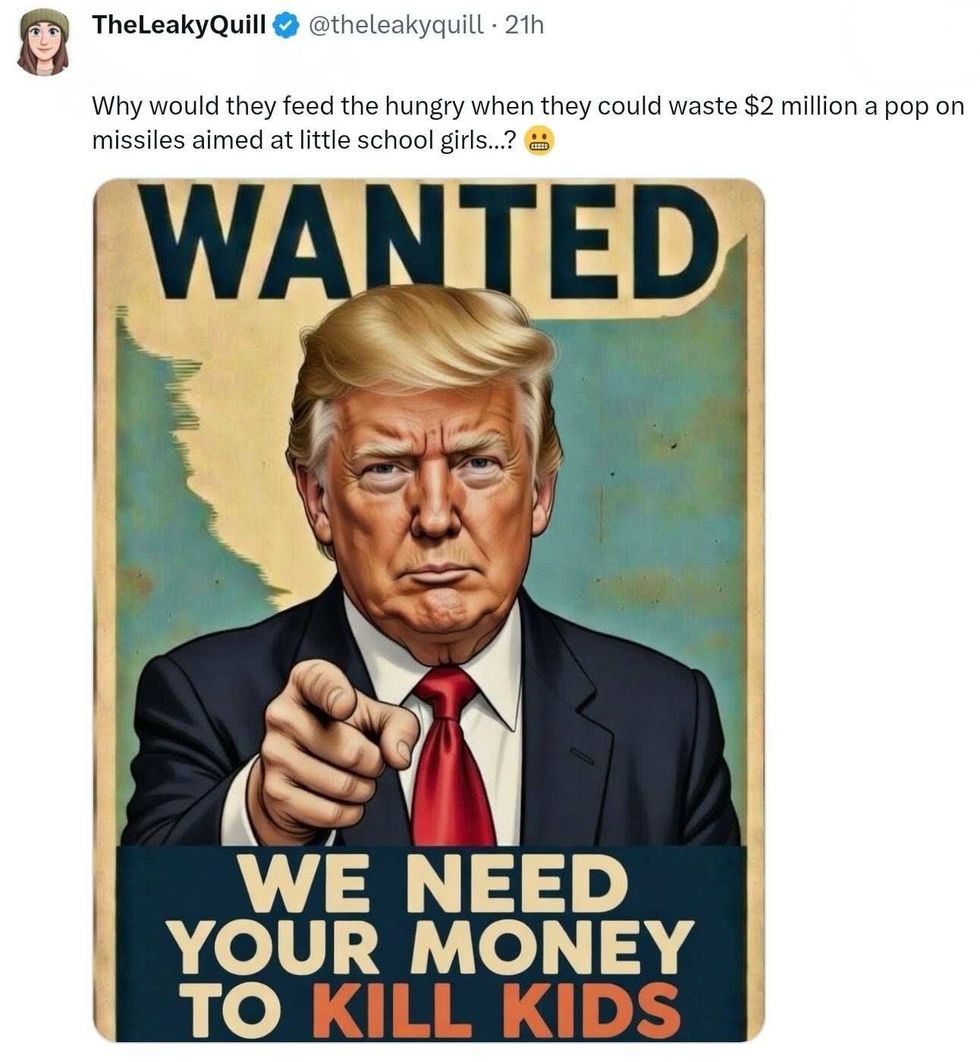

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit @theleakyquill/X

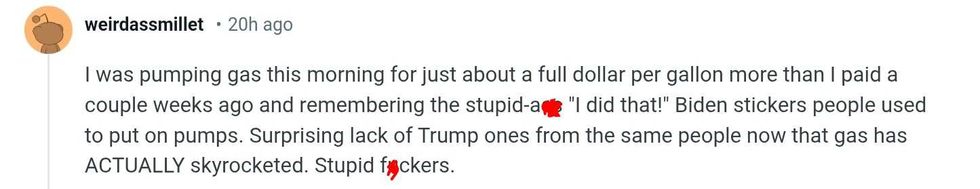

@theleakyquill/X r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit @IsabelM31530319/X

@IsabelM31530319/X r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

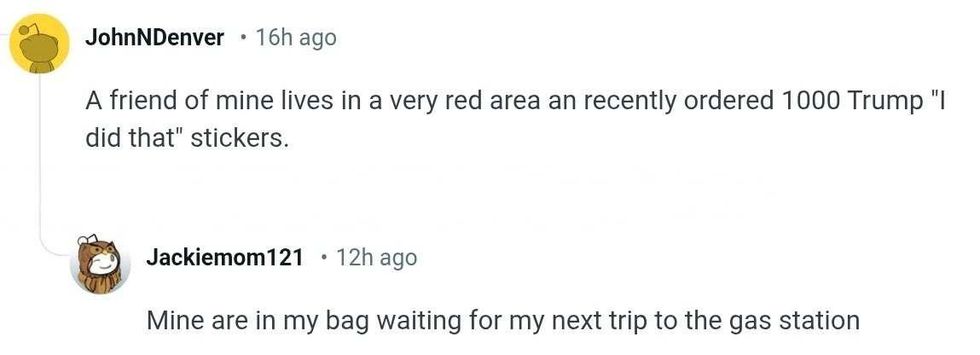

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit @cwyyell/X

@cwyyell/X r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

@newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok

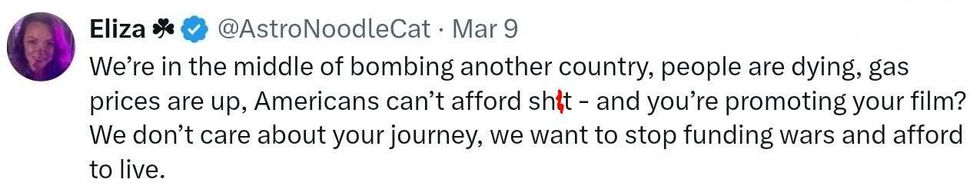

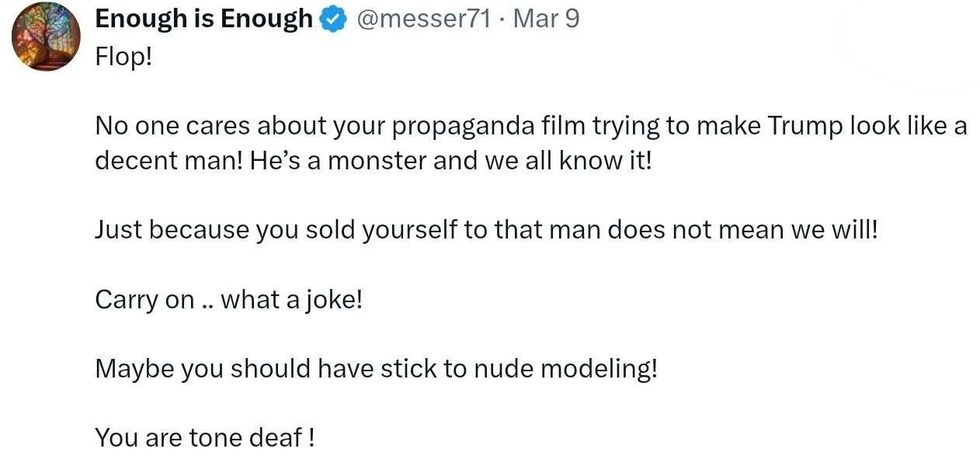

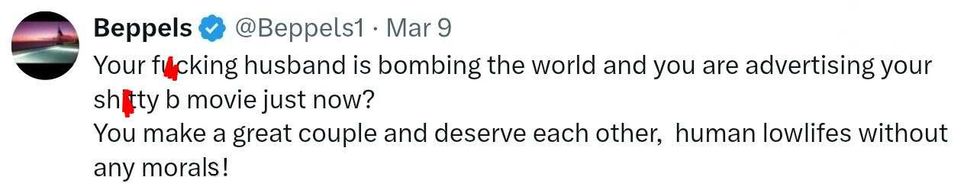

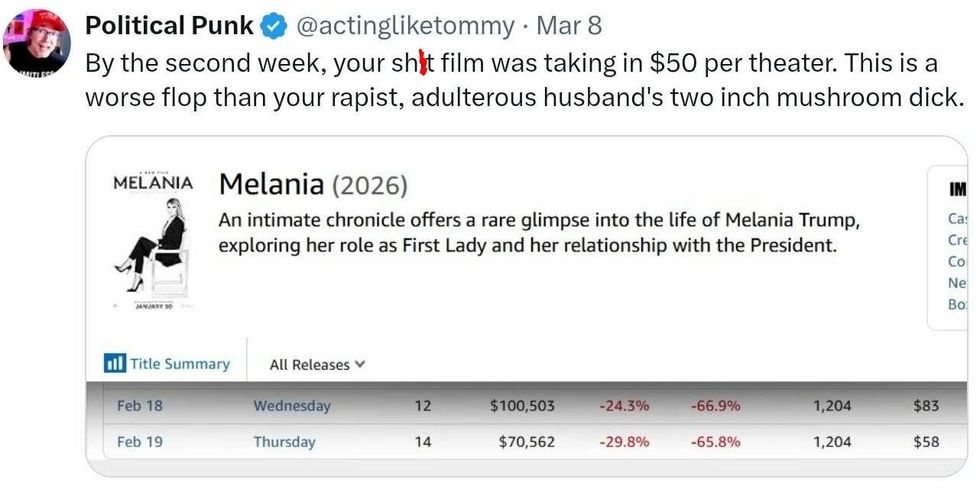

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X