A research team from Yale University has managed to restore some brain function in the brains of pigs who were killed hours prior.

The team announced their success in a recent paper published in the journal Nature.

Scientists placed the brains of pigs from a nearby slaughterhouse in a solution of chemicals meant to preserve and repair the brain's cells. The solution also contained a medication to prevent the brain from regaining any type of conscious thought.

When scientists tested the brains after 6 hours in the preservation solution, they discovered that they were observably less deteriorated than the brains which were left exposed to air.

Nenad Sestan, of Yale University's School of Medicine, told NPR:

"We found that tissue and cellular structure is preserved and cell death is reduced. In addition, some molecular and cellular functions were restored."

"This is not a living brain, but it is a cellularly active brain."

That emphasis on it not being a living brain is important. Given the ethical concerns such an experiment brings up, the team were extremely careful to make sure that no true consciousness could be restored to the brains.

We have known that some viable cells remain in the brain several hours after it is deprived of oxygen, as scientists have been able to study them this way in the past.

Sesta highlighted the problem with this method of study, though:

"...the problem is, once you do that, you are losing the 3D organization of the brain."

In order to improve how we study the brain, Sesta and colleagues wondered if there wasn't a way to do so while still leaving the cells in a whole, intact brain.

Stephen Latham, a bioethicist that worked closely with the research group, said:

"It was something that the researchers were actively worried about."

Thus, the experiment involved chemicals to ensure that the brain could not regain any sort of consciousness. A medication called lamotrigine, which is used to treat seizures and is known to suppress neuronal activity, was included in the solution that the brains were soaked in.

Latham told NPR that this was also because:

"the researchers thought that brain cells might be better preserved and their function might be better restored if they were not active."

Duke Law School Ethicist Nita Farahany, who focuses on the ethics of emerging technology, said of the experiment:

"It was mind-blowing."

"My initial reaction was pretty shocked. It's a groundbreaking discovery, but it also really fundamentally changes a lot of what the existing beliefs are in neuroscience about the irreversible loss of brain function once there is deprivation of oxygen to the brain."

Khara Ramos, who is the director of neuroethics at the National Institute of Disorders and Stroke, also talked about the importance of continuing to move forward on these experiments in an ethical manner.

"The science is so new that we all need to work together to think proactively about its ethical implications so that we can responsibly shape how this science moves forward."

Farahany and her colleagues Charles Giattino and Henry Greely also published a commentary in Nature alongside their paper. In it, they cite a line from the character Miracle Max in the film The Princess Bride:

"There's a big difference between mostly dead and all dead. Mostly dead is slightly alive."

It seemed many people had the same reaction to the news on Facebook: zombie pigs.

One neuroscientist also tried to address the concerns of those who jumped to the zombie conclusion.

Over on Twitter, people were also concerned with the possible ethical implications, but noted that the team had done a good job addressing them.

This experiment definitely raises some tangled ethical questions, but the researchers are determined to move forward in an ethical manner.

The scientific ethics community is considering how this can be done, and the implications of the findings on the broader reality of experimentation on dead organs.

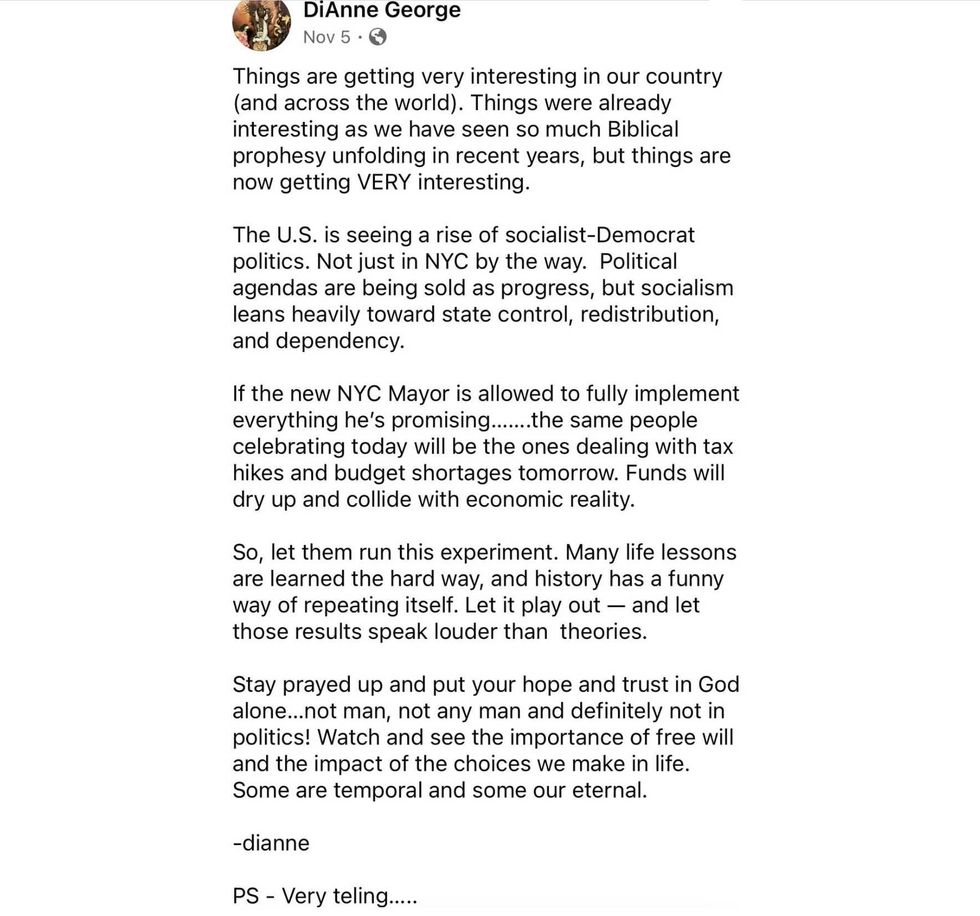

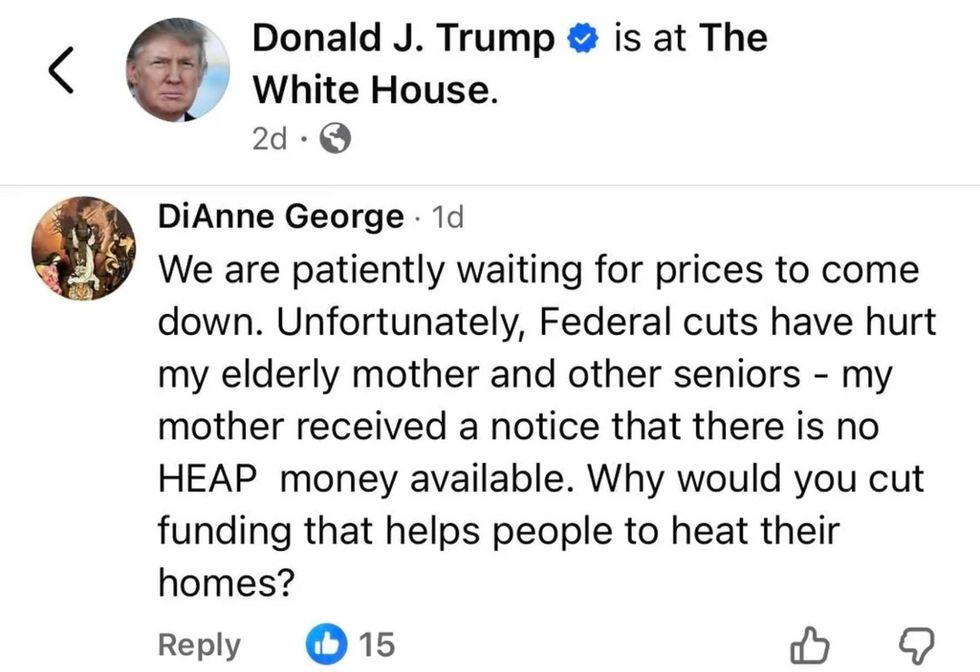

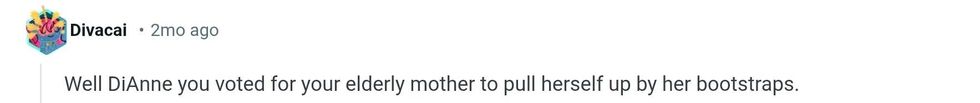

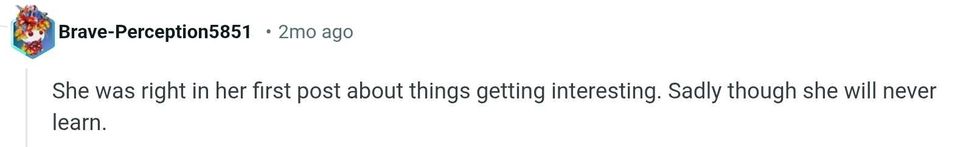

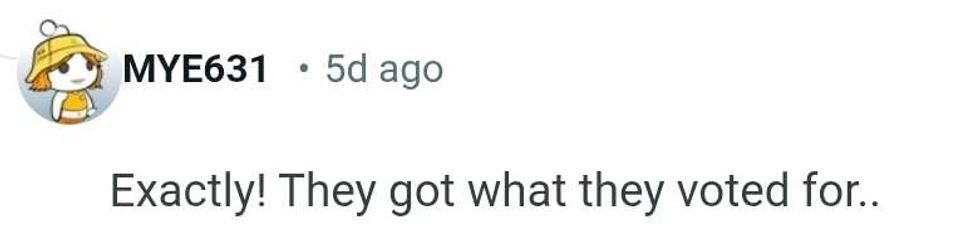

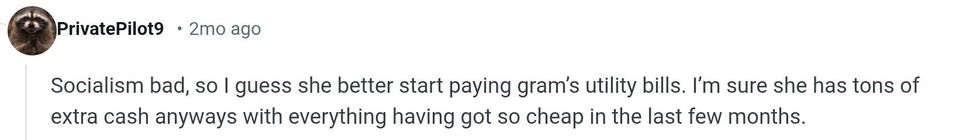

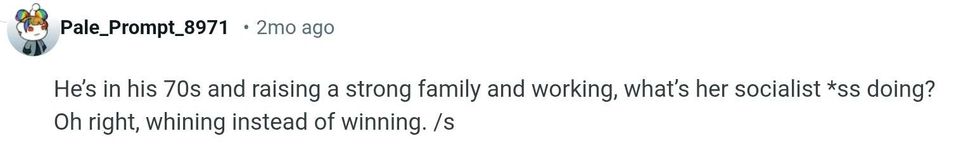

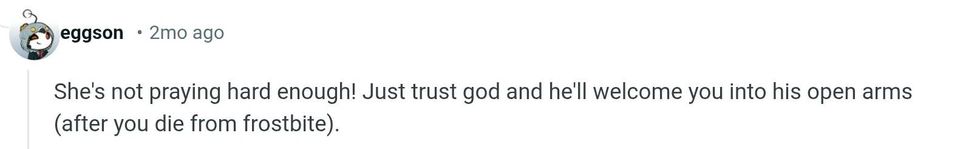

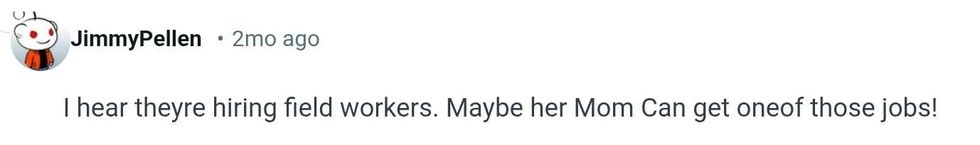

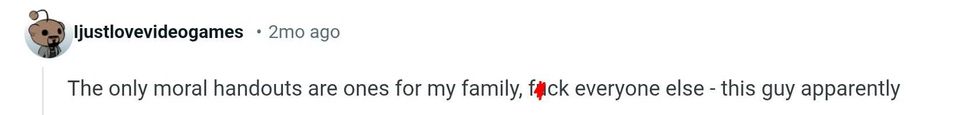

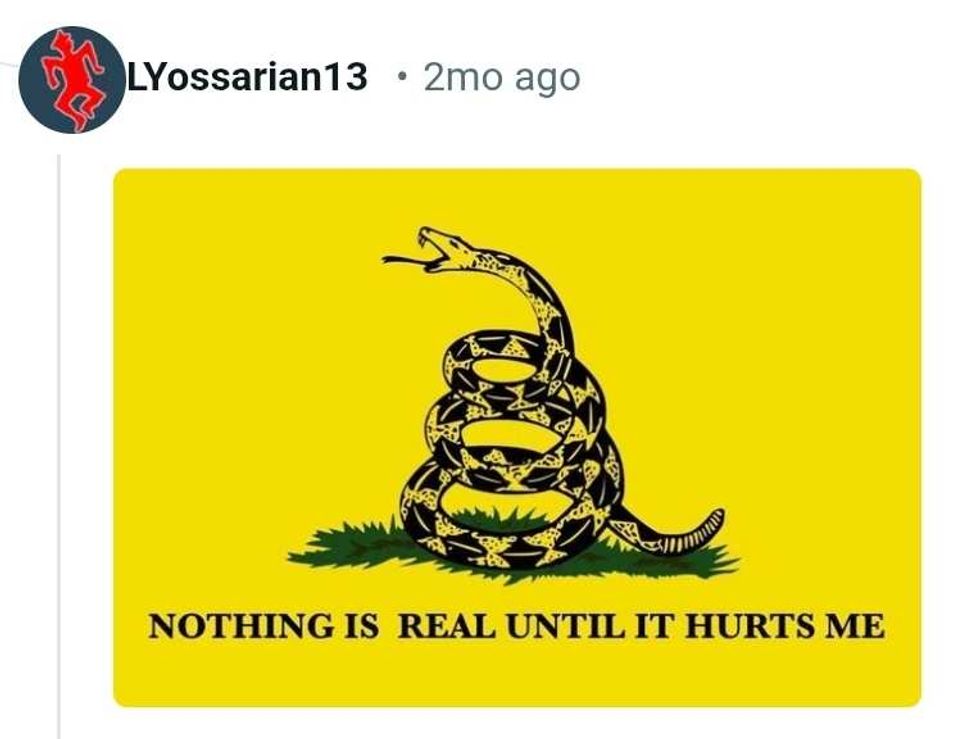

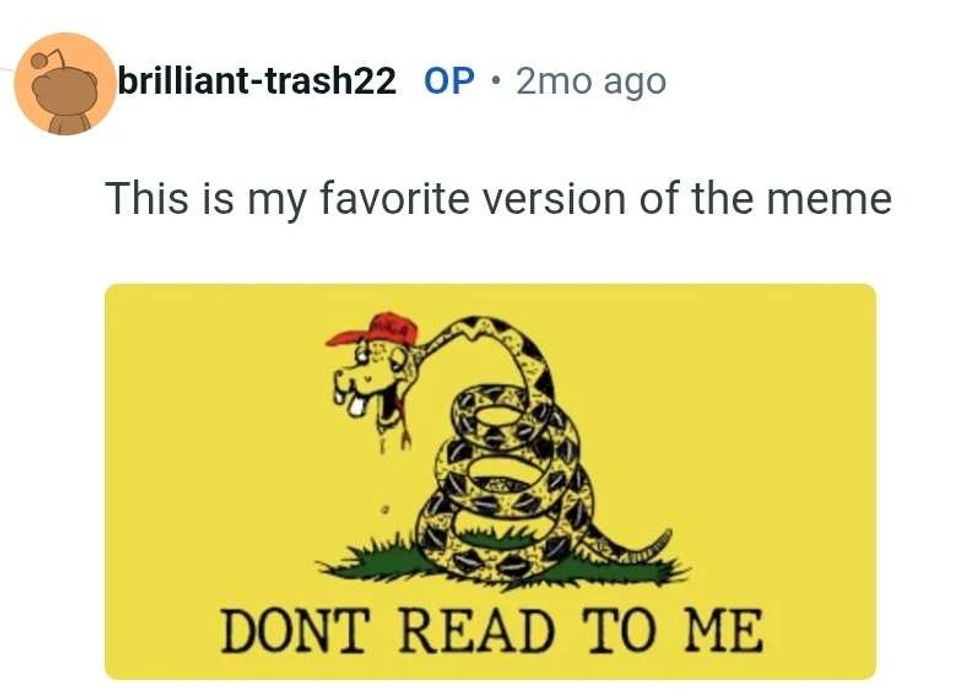

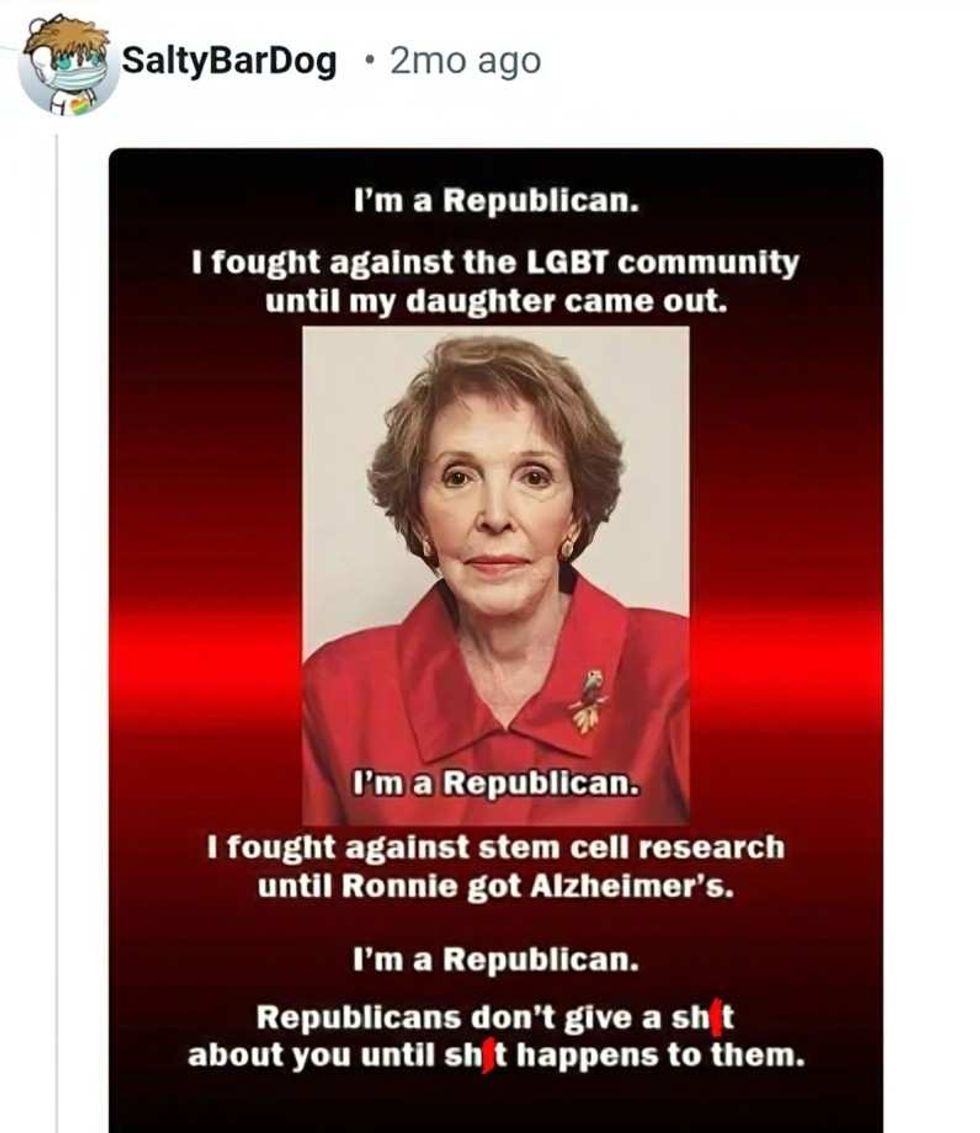

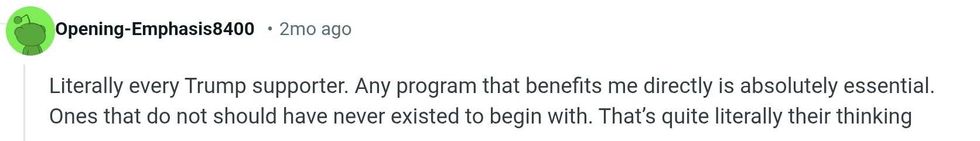

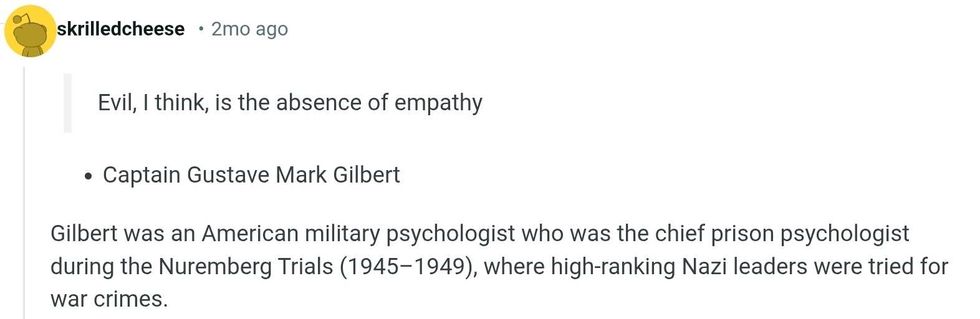

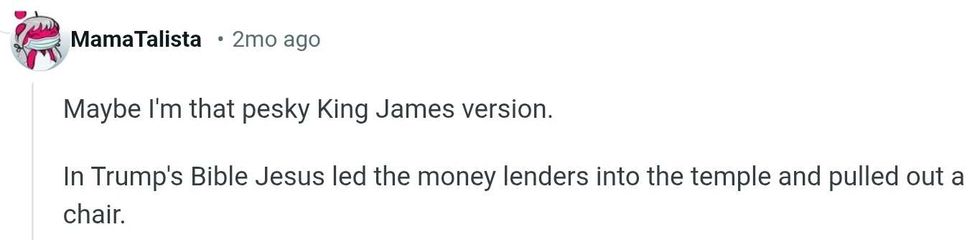

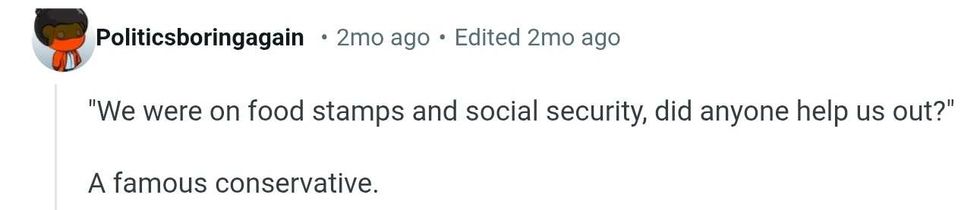

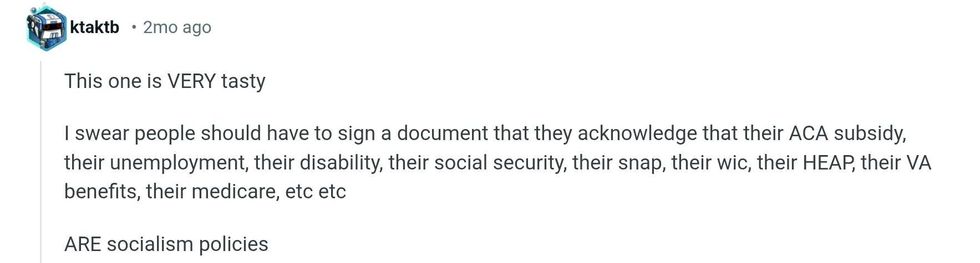

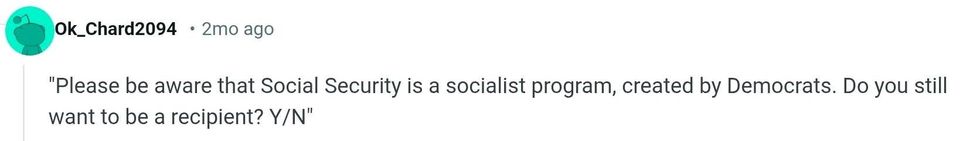

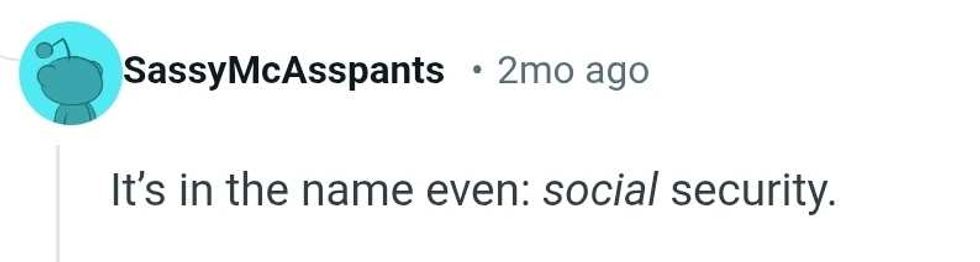

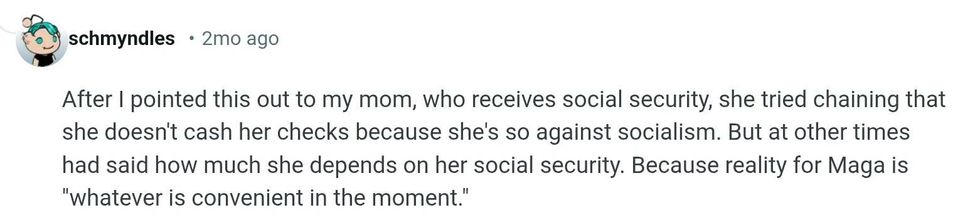

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

@meidastouch/X

@meidastouch/X @meidastouch/X

@meidastouch/X @meidastouch/X

@meidastouch/X @meidastouch/X

@meidastouch/X

illustrate margot robbie GIF

illustrate margot robbie GIF

Bbc One Love GIF by BBC Three

Bbc One Love GIF by BBC Three  Oh Yeah Dancing GIF by Jennifer Accomando

Oh Yeah Dancing GIF by Jennifer Accomando