This paramedic had just finished training when emergency services saved her life. Now, she's opening up about how she was blue-lighted to hospital when a rare bladder condition triggered deadly sepsis, leaving her unable to walk and perform her dream job.

Despite being plagued by urinary tract infections throughout her teens, it was not until 2017 that Zoe Clark was diagnosed with Fowler's syndrome, a condition in which the sphincter muscle in the bladder cannot relax.

Fitted with a sacral nerve simulator (SNS) in April 2018, she was expecting things to get back to normal.

Instead, Clark developed extreme flu-like symptoms, vomiting and even blacking out before a seizure in November 2018 caused her to rush to Crawley Hospital. Where she was diagnosed with sepsis, a potentially life threatening condition caused by the body's response to an infection.

“Doctors told me that the SNS wasn't working properly, urine wasn't clearing from my bladder as they had hoped and it had become infected," Clark said.

“They said the fact I had been on antibiotics most of my adult life had created the perfect conditions for me to develop sepsis."

Sadly, things went from bad to worse for Clark when dream of becoming a paramedic was destroyed when her slow progress led to a further diagnosis in January 2019 of post-sepsis syndrome (PSS), the term applied when recovery from sepsis is particularly long.

“It absolutely breaks my heart not being able to put my paramedic training into place – it's the hardest thing to deal with. I worked my bum off to make the grade, yet it was taken away so quickly," she said.

“I've gone from wanting a career helping others, to being at the complete opposite end of the spectrum and relying on others to help me."

“So many people haven't heard of Fowler's syndrome or PSS, now I want to raise awareness of them both, as they have turned my life on its head."

“As soon as I reached puberty I started coming down with urinary tract infections," she recalled.

“At first, it was once or twice a year, but before long I was having them every month. I'd feel an urgency to wee, accompanied by constant pain. If I did pee, it would be hardly at all and I'd experience really uncomfortable stinging."

“I remember sleeping on the bathroom floor or in the bath many times, just to be close to the toilet," she continued.

Luckily, when she started training as a paramedic in September 2014, Clark's flare-ups had reduced to just once or twice a year.

“At the time, I was a part-time care assistant and had studied health and social care at college," she said.

“But a family friend of ours was a paramedic, I really admired them and loved hearing the stories, so it was my dream job," she said.

Studying at the University of Portsmouth in Hampshire, Clark also completed hands-on placements and classroom learning.

Qualifying in the summer of 2016, Clark and her parents, Kerrie and Graham, helped her celebrate with a week-long trip to Alicante, Spain.

Just days into the vacation, she woke up in agonizing pain and was rushed to a nearby hospital.

“I woke up in absolute agony," she said. “It was like my bladder was going to burst."

“At first, I tried going to the toilet, but it wouldn't work. I thought I would pass out from the pain, it was so bad."

After a physical examination, Clark was fitted with a catheter to empty her bladder.

“I don't remember much from the hospital – I was in so much pain. But I do remember that the doctor couldn't believe just how much urine had been stored in my bladder," she said.

Returning home, Clark found herself in a vicious cycle suffering extreme urine retention and then needing to visit Crawley Hospital every week to be catheterized.

“Nobody could tell me what was causing it," she said. “It came on out of nowhere and never left. It was terrifying – suddenly not being able to pee."

After Spain, Clark learned to self-catheterize, which helped while she waited to be seen by a specialist urologist at University College London Hospital (UCLH) in early 2017.

In constant agony, she already feared that she would never put her paramedic skills into practice.

“I was in too much pain by that point to work at all," she recalled.

“I physically struggled to function," she said.

Finally, at the start of 2017, Clark had a series of tests at UCLH, where she was diagnosed with Fowler's syndrome.

“Medics said it was very clear that it was Fowler's, but that not many doctors were familiar with the condition," she said.

“I was just relieved to have a diagnosis after all this time," she said.

In April 2018, she was fitted with an SNS only for the device to fail, leading to her diagnosis later that year of sepsis followed by PSS.

“I was in hospital from November to January," she said. “It genuinely felt like I was dying."

“I could barely speak properly. My arms were constantly shaking and I couldn't use my legs at all – they were too weak," she said.

With no treatment available for PSS, in February Clark was transferred to a rehab facility at Horsham Hospital, West Sussex, where she spent four months learning how to perform basic tasks, like sitting up in bed and getting in her wheelchair.

Discharged in June 2019, after being fitted with an indwelling catheter draining urine through a tube connected to the bladder via the urethra, which is collected in an external bag. Clark has been living with the help of carers ever since.

“Doctors tried to get me to walk, but it just wasn't happening – my body just doesn't want to," she said.

“Carers have to come and help me shower, help me go to the toilet. I've had my entire life tipped upside down. They come in and I'll be in bed and when they leave, I'm in bed."

Thankfully, a consultation in early August has now given Clark a glimmer of hope.

“They told me I'm the perfect candidate to have my bladder removed and reconstructed using my bowel," she said.

“They would use part of my small intestine and create a pouch in the same place as my bladder," she continued.

“But the waiting list for UCLH can be at least 18 months to two years – at best – even on an urgent referral. Still, it's offered me some form of hope, which is the main thing."

Now, Clark is determined to help other women to get an early diagnosis of Fowler's and PSS.

“I'm going to be stuck in this position for a long time and the pain from my Fowler's can be genuinely life-limiting," she said.

“I feel like I've had all my dignity and everything I used to enjoy taken away."

It has impacted every aspect of her life.

“I've gone from being a really active person, running and swimming several times a week, to barely being able to get out of bed and unable to even make a cup of tea because of my tremors," she continued.

“Before being struck down by this illness, I loved going out for meals with my friends and enjoyed shopping trips, now I'm limited to home visits or talking over social media."

“But I'm determined to make the best out of a difficult situation."

“My first dream is to get back to work full-time, but my second is to help other women with Fowler's and PSS to get a diagnosis as soon as possible," she said.

“Maybe if I'd been diagnosed as a teenager, I wouldn't be in the position I am now."

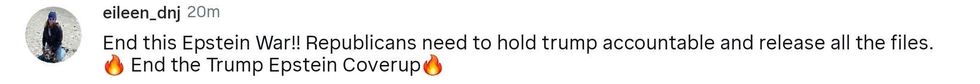

@CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram @CNN/Instagram

@CNN/Instagram

Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images

Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images