Dravet syndrome, a rare but severe and deadly form of epilepsy which kills at a rate 30 times higher than other childhood-onset epilepsies, has perplexed scientists for years. Now, a new study has shown that the cure might be present in, of all things, tarantula venom.

Researchers have, since Dravet syndrome was identified more than 30 years ago, learned Dravet syndrome cases are caused by a genetic mutation that impedes function in a gene known as SCN1A. The gene produces a protein called Nav1.1. that controls the electrical properties of neurons in the brain, and children with Dravet syndrome do not produce enough of the protein to control this electric activity (epileptic seizures result from a disturbance in electric activity in the brain).

According to The Conversation:

In the brain, Nav1.1 exists predominantly in a group of neurons that are responsible for calming brain activity. A malfunction in Nav1.1 inhibits that calming ability, leading to seizures.The brain begins producing Nav1.1 in the weeks following birth, with production increasing as a baby ages. This may explain why Dravet syndrome does not become apparent until five to eight months after birth.

Australian researchers from the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and the University of Queensland published a study this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America which found that the venom of the West African Tarantula contains peptides that produce proteins, which have been known to prevent epileptic seizures. The researchers tested their hypothesis on mice, finding that the tarantula venom reduced seizures in mice with Dravet syndrome and even lengthened their lifespans.

"Most treatments for epilepsy are looking at tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of drugs, hoping to find one that stops the seizures. We did this in one step, which shows how precision medicine works with fundamental knowledge of the disease," said Professor Steven Petrou, director of the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and the study's lead author.

Petrou added that this research is an example of "precision medicine," which is, according to the Precision Medicine Initiative, defined as "an emerging approach for disease treatment and prevention that takes into account individual variability in genes, environment, and lifestyle for each person."

PMI notes that this approach can:

allow doctors and researchers to predict more accurately which treatment and prevention strategies for a particular disease will work in which groups of people. It is in contrast to a one-size-fits-all approach, in which disease treatment and prevention strategies are developed for the average person, with less consideration for the differences between individuals.

Thus far, the study has only been performed on mice, and Petrou says "that look at specific genetic changes like this one show higher rates of success when transferred to human trials compared to traditional animal experiments," according to Buzzfeed News.

Tarantula venom paralyzes the small invertebrates tarantulas typically prey on, so the effect it has on the brains of those with Dravet syndrome is not surprising, says Petrou. The venom keeps the SCN1A-produced protein sodium channels open.

We are exploiting this effect for clinical use," said Petrou. "We know already that biology has spent millions of years fine-tuning the action of these peptides in order to incapacitate prey and we thought, 'Can we use them in a way that might be medically useful?'"

Petrou and his team believe a tarantula venom treatment could not only stop seizures but also reverse developmental disabilities associated with Dravet syndrome if the treatment is applied early enough. Children with Dravet syndrome have a higher risk of sudden death (seizures are frequent, often coming without warning) and appear normal in the first few months after birth, but develop behavioral delays in their second year of life, including:

- mild to severe mental retardation

- sleep disturbances

- personality disorders (including social isolation and frequent mood swings)

Understandably, a development as valuable as this one could go a long way in reducing anxieties in families who have children who are affected.

"We've shown a very important proof of concept that if you alter the function of a protein this way with a drug, you can fix seizure controls, you can fix the neurons, and you can fix all of the other things that go wrong related to that," Petrou says, adding that he and his team will work with companies to develop the tarantula venom into a drug for human trials.

Roberto Schmidt/AFP via Getty Images

Roberto Schmidt/AFP via Getty Images

u/pizzaratsfriend/Reddit

u/pizzaratsfriend/Reddit u/Flat_Valuable650/Reddit

u/Flat_Valuable650/Reddit u/ReadyCauliflower8/Reddit

u/ReadyCauliflower8/Reddit u/RealBettyWhite69/Reddit

u/RealBettyWhite69/Reddit u/invisibleshadowalker/Reddit

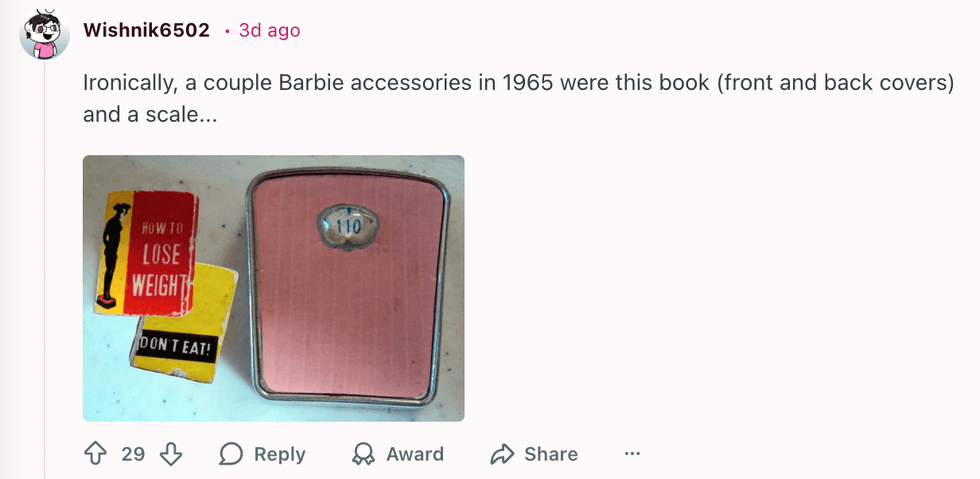

u/invisibleshadowalker/Reddit u/Wishnik6502/Reddit

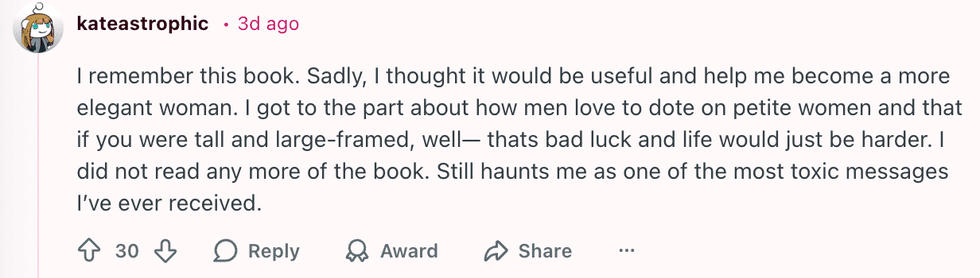

u/Wishnik6502/Reddit u/kateastrophic/Reddit

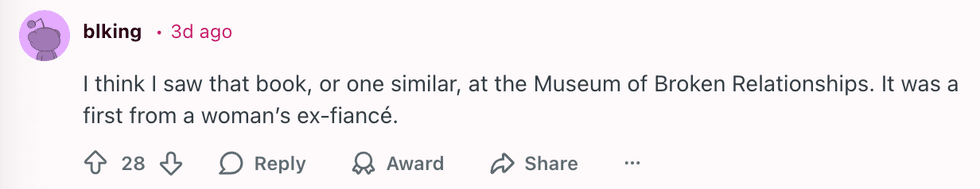

u/kateastrophic/Reddit u/blking/Reddit

u/blking/Reddit u/SlagQueen/Reddit

u/SlagQueen/Reddit u/geezeslice333/Reddit

u/geezeslice333/Reddit u/meertaoxo/Reddit

u/meertaoxo/Reddit u/crystal_clear24/Reddit

u/crystal_clear24/Reddit u/stinkpot_jamjar/Reddit

u/stinkpot_jamjar/Reddit

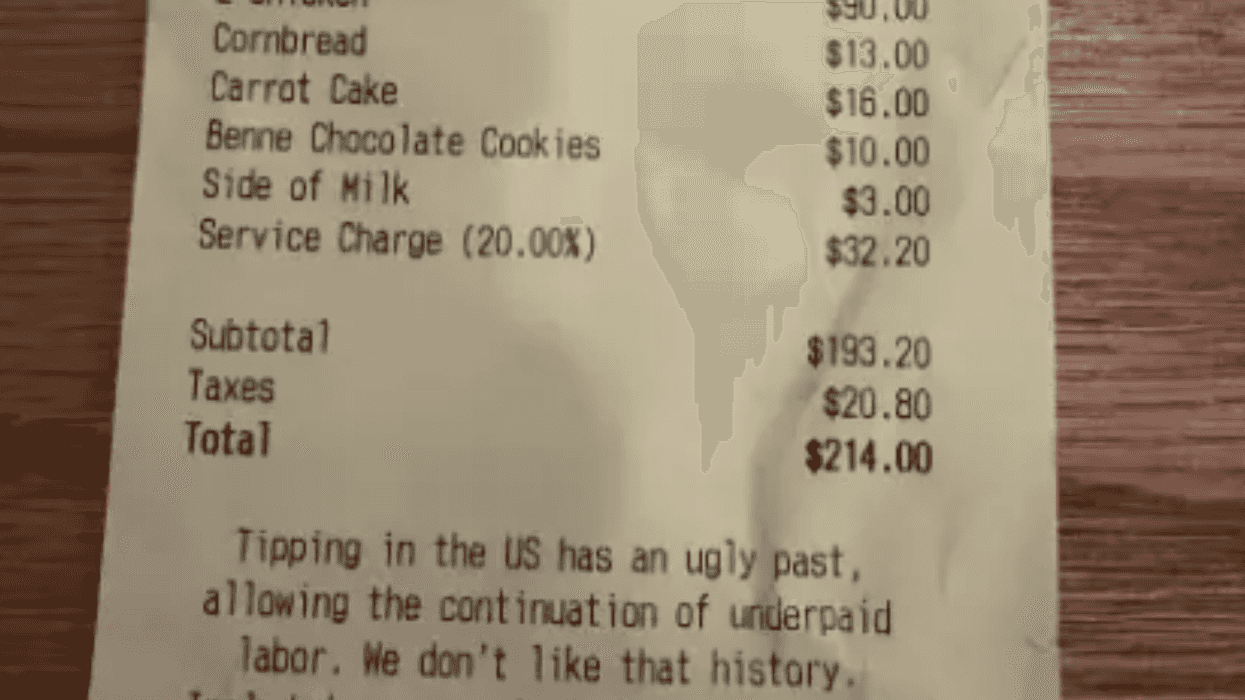

u/Bulgingpants/Reddit

u/Bulgingpants/Reddit

@hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok @hackedliving/TikTok

@hackedliving/TikTok

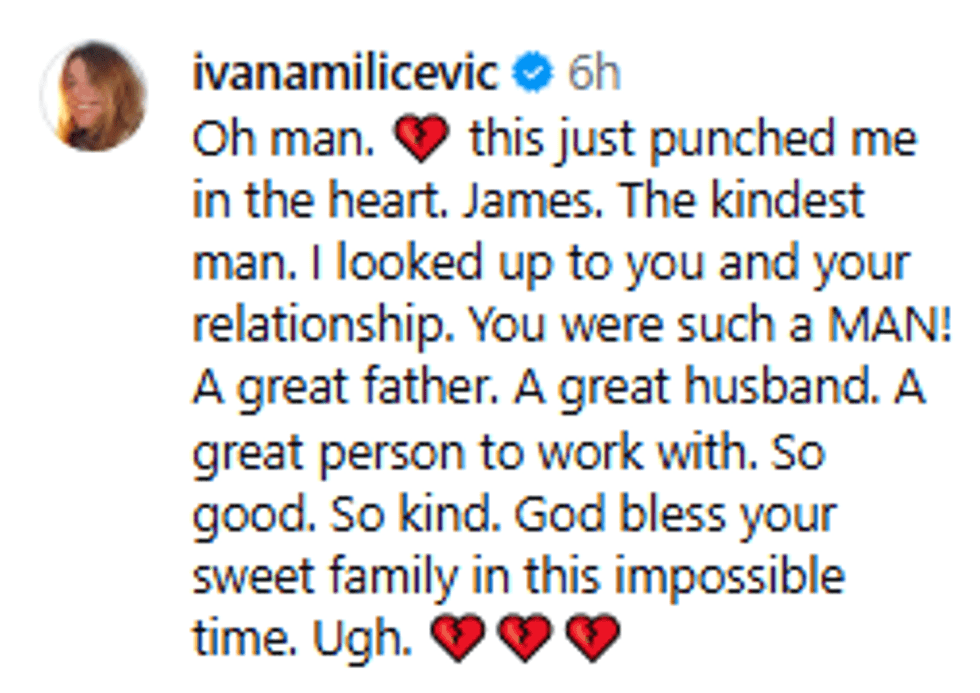

@vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram @vanderjames/Instagram

@vanderjames/Instagram