A local expert warned Virginia swimmers that Naegleria fowleri, a potentially deadly micro-organism otherwise known as the “brain-eating amoeba,” was prevalent in most bodies of water in the region. The amoebas divide and multiply during hot summer months, and infections are higher during the months of July and August. “It doesn’t just happen when you are swimming,” said Dr. Francine Marciano-Cabral, with VCU’s Department of Microbiology and Biology. “It’s really when you fall off your skis or out of the boat.” Dr. Marciano-Cabral stressed that drinking lake or river water would not result in infection. The pathogen infects in humans when inhaled through the nose, and uses the brain as a food source. It then proceeds to feed on tissue, causing headache, nausea, fever and vomiting. Later symptoms include loss of balance, seizures, and hallucinations.

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, amoeba infections are rare. There are only 162 reports of infection between 1962 and 2015. However, only three people have ever survived it. Most people, says Dr. Marciano-Cabral, fail to diagnose the problem quickly enough. Symptoms take up to 15 days to appear, and death will usually occur within two weeks thereafter. She recommended plugging or holding your nose when jumping or diving into fresh bodies of water and avoiding murky or dirty waters to mitigate the risk of infection.

Dr. Marciano-Cabral’s warning comes a month after a teenager died while on a rafting trip at the U.S. National Whitewater Center in Charlotte, North Carolina. Researchers with the CDC detected a high level of brain-eating amoebas at the waterpark. All 11 samples taken from the waterpark tested positive for the pathogen. Samples taken from the nearby Catawba River tested negative, though researchers did find the amoeba in a sample taken from the riverbed. “Our findings here are significant,” said Dr. Jennifer Cope, an infectious disease physician at the CDC. “We saw multiple positive samples at levels we’ve not previously seen in environmental samples.”

An inadequate water sanitation system, noted Dr. Cope, is the likely reason for the amoeba’s presence. The park relies on ultraviolet and chlorine to clean its waters. These conditions usually kill Naegleria fowleri. However, the park’s man-made bodies of water are designed to look natural: The dirt and debris collected overtime interferes with the sanitation process. “The chlorine reacts with all that debris and is automatically consumed so that it is no longer present to deactivate a pathogen like Naegleria and the same is true about UV light,” Dr. Cope said.

The U.S. National Whitewater Center is also one of only three park systems in the country exempt from regular testing for pathogens. Health officials view the park as more of a river, despite the park’s recirculation of more than 12 million gallons of water, much of it via the city’s municipal water system. These regulations are “being questioned for the future,” according to Dr. Stephen Keener, the Mecklenburg County Medical Director. Dr. Kenner noted that while the risk of infection is extremely rare, changes to the filtering system are in the works. “We don’t know very much about how Naegleria lives and grows in systems like this,” he continued, “but factors such as soil runoff, uneven surfaces, stones on the bottom where slime can grow, along with shallow channels that allow water to warm quickly on hot days, makes it a unique environment.” A plan to remediate the channels will be put in motion once officials figure out the safest way to remove the amoebas without placing sanitation workers at risk.

Reset Era

Reset Era r/WorkReform/Reddit

r/WorkReform/Reddit r/WorkReform/Reddit

r/WorkReform/Reddit Reset Era

Reset Era Reset Era

Reset Era r/WorkReform/Reddit

r/WorkReform/Reddit Reset Era

Reset Era r/WorkReform/Reddit

r/WorkReform/Reddit Reset Era

Reset Era r/WorkReform/Reddit

r/WorkReform/Reddit Reset Era

Reset Era Reset Era

Reset Era r/WorkReform/Reddit

r/WorkReform/Reddit Reset Era

Reset Era r/WorkReform/Reddit

r/WorkReform/Reddit Reset Era

Reset Era r/WorkReform/Reddit

r/WorkReform/Reddit

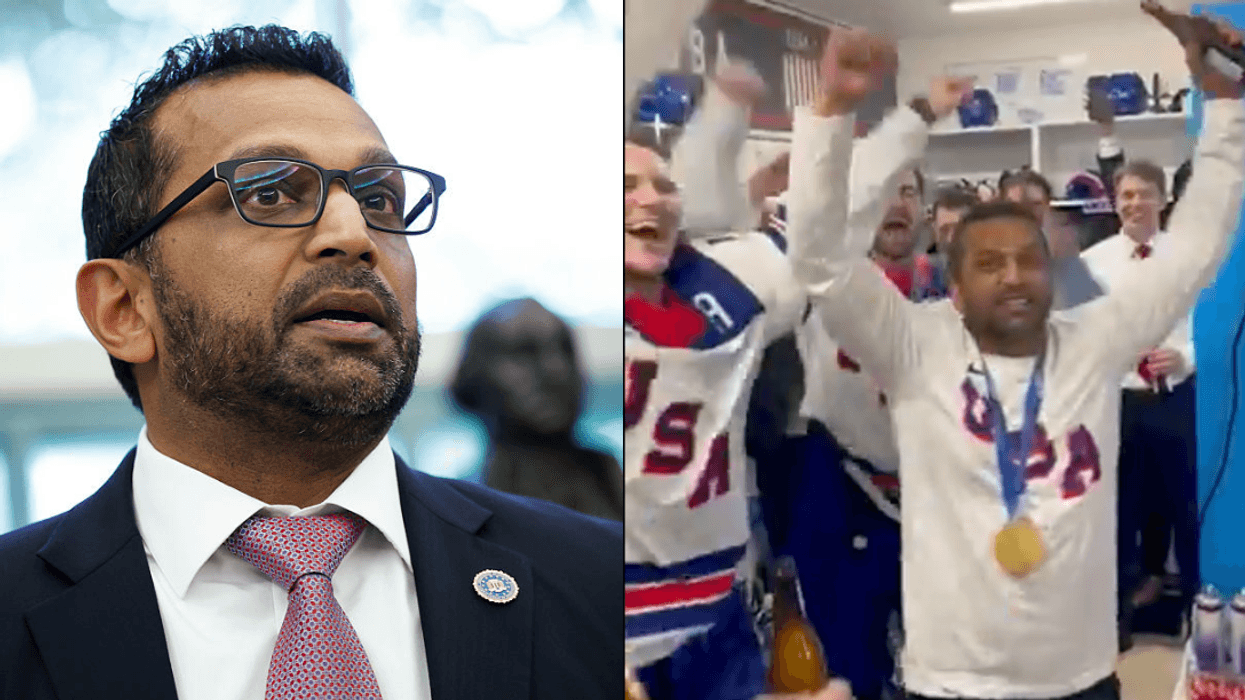

@SecDuffy/X

@SecDuffy/X

@WhiteHouse/TikTok

@WhiteHouse/TikTok @WhiteHouse/TikTok

@WhiteHouse/TikTok @WhiteHouse/TikTok

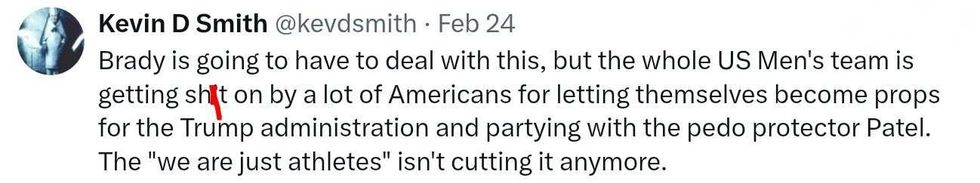

@WhiteHouse/TikTok @kevdsmith/X

@kevdsmith/X