In his historic address to Congress—the first ever given by a leader while sheltered in a bunker in the middle of a war—President Volodymyr Zelenskyy spoke passionately about his nation’s plight, reminding Congress that every night in Ukraine was like Pearl Harbor or 9/11. As expected, he repeated his call for the U.S. and NATO to close the skies over Ukraine by imposing a no-fly zone. At the same time, he seemed to acknowledge that a no-fly zone was a red line for the U.S. that it would not cross and asked in the alternative for surface-to-air missile systems so that Ukraine could shoot down Russian bombers on its own.

What is it about closing the skies over Ukraine that has NATO leaders and the White House on edge? After all, there were no-fly zones imposed in the first Iraq war, in Bosnia, and more recently in Libya. What’s the difference here?

Polls show that Americans broadly favor such a move. In early March, a Reuters/Ipsos poll showed that 74 percent of U.S. respondents favored imposing a no-fly zone. But that number could be a function of a lack of full understanding of what such a declaration actually entails. When asked whether they would favor shooting down Russian planes flying over Ukraine, support flipped, according to a more detailed YouGov poll that sought to ask more specifics about the zone, with 46 opposed and only 30 percent in favor. And a recent CBS News poll showed that a strong majority actually opposes a no-fly zone if it was viewed as an act of war by Russia, with 62 opposed and 38 in favor.

These polls show that the American public is unclear what closing the skies really would mean—an understandable confusion given our history of imposing these zones before. At the risk of oversimplification, as these matters are highly complex, the arguments break down basically as follows.

Those opposing a no-fly zone argue that imposing it on a small military power like Iraq or Libya is one thing, but imposing it on a military the size of Russia’s is another. Indeed, Russia has warned that it would view any U.S. or NATO planes in Ukrainian airspace as “participants of the military conflict,” suggesting a military response from Russia would be likely. This threat has to be taken seriously given Russia’s military capabilities and nuclear weapons. Further, opponents point out that most of the damage being caused to Ukrainian cities is from artillery shelling and missiles, which wouldn’t be halted by a no-fly zone. Indeed, the Russian air force has been unusually inactive in the war, perhaps because of the very real threat from surface to air missiles provided to Ukraine by the U.S. and its allies. When their fighters do engage, they are often firing missiles from well within Russian airspace. A no-fly zone wouldn’t be able to stop those missiles either.

Opponents note that declaring a no-fly zone also means being willing to enforce it, which necessarily involves targeting both Russian aircraft currently operating in Ukraine (such as bombers and attack helicopters) as well as bombing air defense systems inside Russian territory. That would mean direct confrontation between NATO and Russian forces, which could escalate quickly into World War III. Ominously, Russia has not ruled out using its most deadly battlefield weapons—tactical nuclear missiles—in order to achieve its military objectives. Such a use would likely trigger a response by NATO to eliminate the threat quickly, meaning there could be a race by both sides to deploy the weapons before they are rendered useless.

Finally, a no-fly zone carries a host of unknown risks, including the strong possibility of shooting down the wrong planes. This happened with the U.S. Air Force in the Gulf War when U.S. fighters targeted two U.S. Blackhawk helicopters by accident, killing 15 Americans and 11 foreign officials on board. Where there is active conflict, the risk of error is understandably high and the consequences are often fatal.

Those in favor of the no-fly zone argue that Putin has already escalated the conflict and inevitably will view NATO’s inaction as weakness. Earlier this week, Russian missiles struck an airbase training foreign volunteer fighters, killing nearly three dozen and wounding many scores—and that was just miles from the Polish border. Pretending that NATO ultimately will not be drawn into this conflict only prolongs the suffering of millions who are besieged in Ukrainian cities and may encourage Russia to set its eyes on other countries such as Moldova or Georgia. On the other hand, imposing a no-fly zone now could prove militarily decisive and break the last of the Russian forward offensive, which already has faltered badly and failed to achieve its primary objectives, including the quick capture of the capital.

Further, refusing to impose a no-fly zone because of fear of engaging Russian fighters ignores that such engagements occurred in other wars. “Americans squared off with Soviet pilots operating under Chinese or North Korean cover in the Korean War without blowing up the world,” argued Bret Stephens, a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist, in the New York Times. “And our vocal aversion to a confrontation is an invitation, not a deterrent, to Russian escalation.” The history of world wars is one of gathering waters before a breach, not of sudden bursts, Stephens pointed out. Before the main invasion of Ukraine, there was its assault upon Georgia in 2008 and annexation of Crimea in 2014, which occurred without anything more than economic sanctions. In other words, Putin won’t stop at Ukraine, and as Fiona Hill, a former senior director of Europe and Russia at the U.S. National Security Council, has warned, we are already in World War III, whether we acknowledge it or not.

Some proponents of closing the skies over Ukraine also argue that it is unnecessary to declare a no-fly zone over all of the country if the risks of war with Russia grow too high, but that a more limited no-fly zone could be imposed over the Western regions in order to secure critical supply lines and humanitarian corridors wherever possible. This would send a clearer message to Putin that his war cannot expand westward into NATO territory and change the calculus away from an all-or-nothing posture.

A no-fly zone could be put back on the table by Russian escalation as well. Some U.S. experts are increasingly worried that Russia will turn to more deadly weapons such as chemical or biological ones, especially given that his ground offensive is stymied and his air forces have not achieved air superiority. This concern increased markedly after Russian disinformation campaigns around alleged U.S./Ukrainian “biolabs” began to circulate, leading to a very real concern that they were a precursor to a “false flag” operation where Russia would claim an incident arose not from Russian missiles but from Ukranian chemical munitions or outlawed weapons labs—which of course do not exist. President Biden has warned Russia that it would pay a “severe price “ for the use of chemical weapons, but what that price might be was not articulated—a strategic ambiguity that most likely is intentional. Whether it could lead to a total no-fly zone or a more limited one, for example, has not been openly discussed, but the possibility remains, with the hope that this will deter Putin from their use.

For now, President Biden has sided with the opponents of a no-fly zone, but he is under increasing pressure to do more to help Ukraine, particularly after President Zelenskyy’s address to Congress last Wednesday morning. After showing graphic and heart wrenching videos of the bombings and atrocities occurring within Ukraine, Zelenskyy made his case once more. Addressing President Biden directly, the Ukrainian president said, “I wish for you to be the leader of the world. Being the leader of the world means to be the leader of peace.”

For additional political analysis, check out the Status Kuo newsletter.

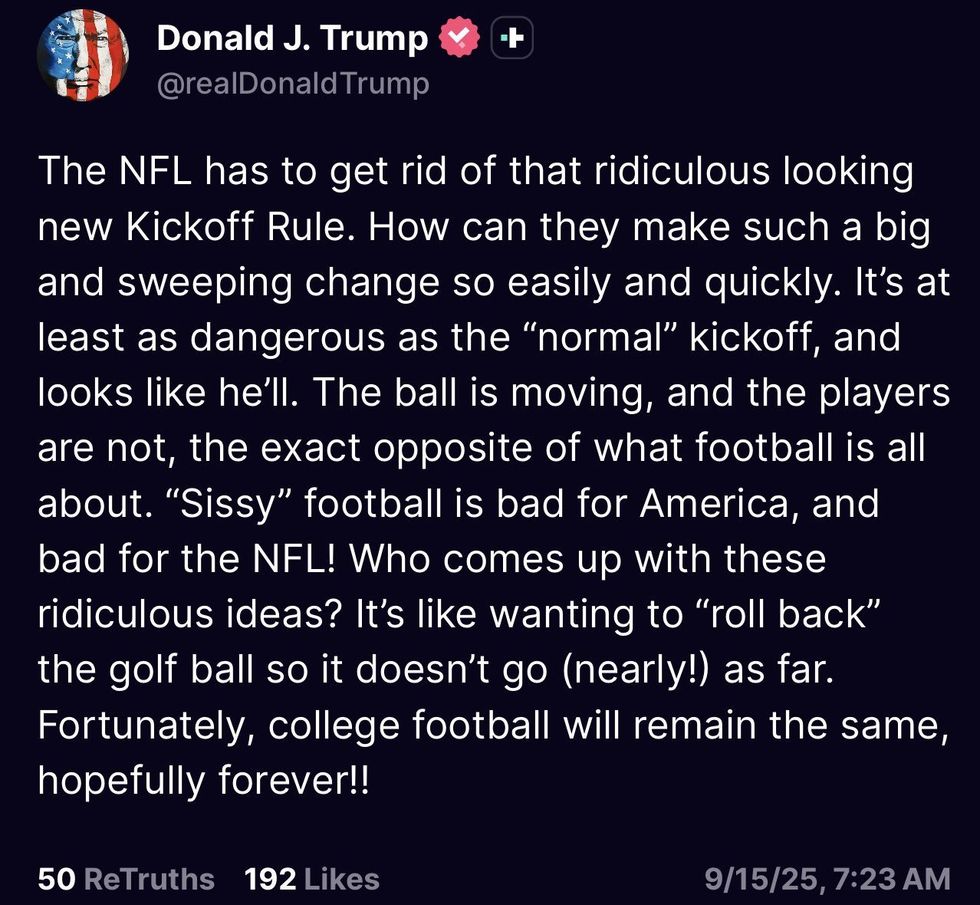

@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social

@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social

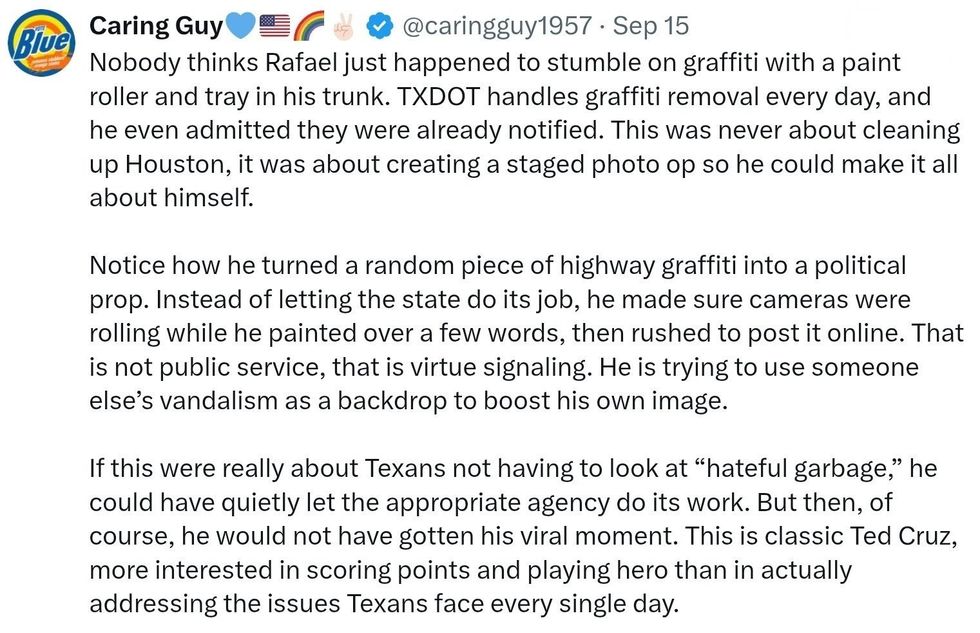

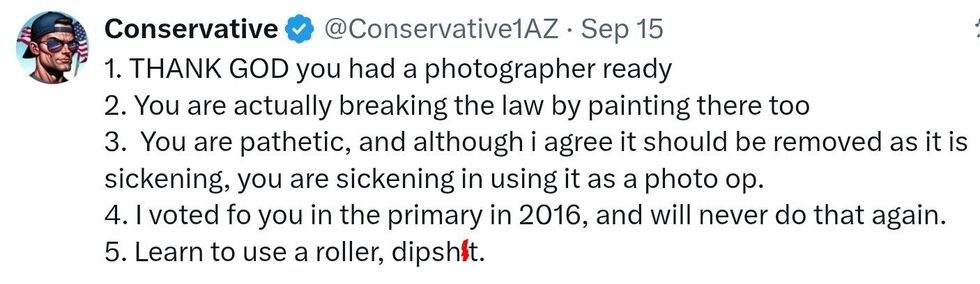

@tedcruz/X

@tedcruz/X @tedcruz/X

@tedcruz/X @tedcruz/X

@tedcruz/X