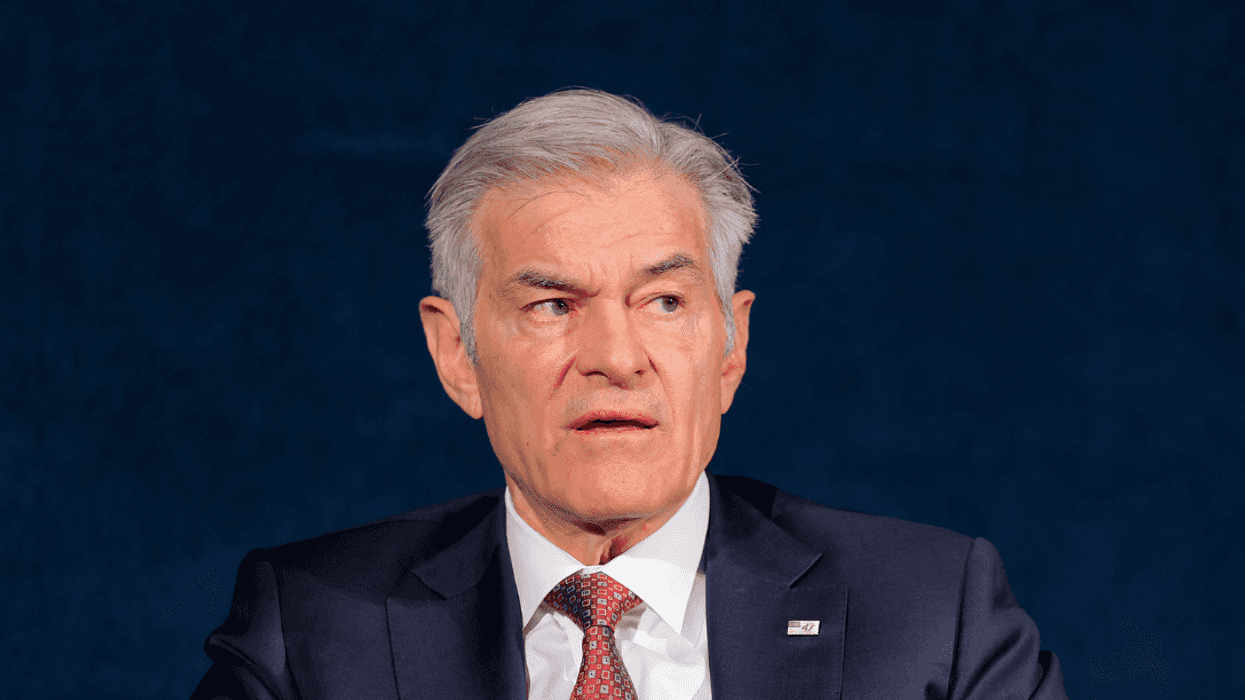

Years after launching its investigation into the financial and tax practices of the Trump Organization in New York, the Manhattan District Attorney’s office apparently has managed to squeeze out a plea deal from that company’s mercurial CFO, Allen Weisselberg.

The deal, as reported by The New York Times, requires Weisselberg to testify against his own company at its upcoming trial in October in exchange for a lenient sentence of as little as 100 days in prison despite admitting to 15 felonies.

The charges center around a fraudulent, off-the-books compensation scheme where perks like apartments and tuition for his children were paid for by the company but not reported to the IRS as income. Weisselberg’s testimony likely means the Trump Organization will be found guilty and will pay a criminal penalty that could cripple it financially.

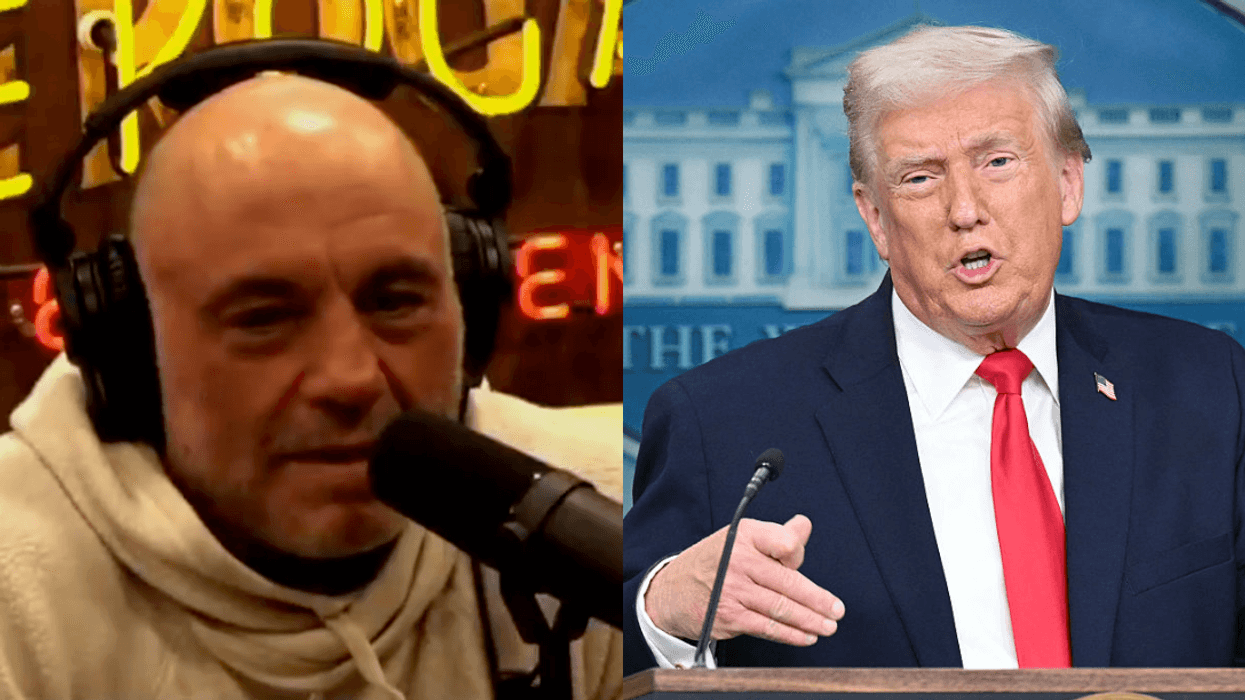

Notably absent from this deal is any agreement by Weisselberg to testify against his boss, Donald Trump, in this case or in any broader investigation. Trump is not currently charged in this matter, given his likely defense that he just allowed others in the company to manage its finances and tax reporting and that he signed off on budgets and checks unwittingly, never having intended to defraud the state out of tax revenues.

Without someone willing to testify otherwise, and with no paper trail connecting Trump to knowledge of the scheme, prosecutors in the end likely determined there was no realistic way to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Trump was part of the planning and the conspiracy to commit tax fraud.

This mirrors the problems the Manhattan DA’s office has had proving its other criminal matter relating to fraudulent financial statements. That investigation, which has a parallel civil investigation by the New York Attorney General, Letitia James, is focused on how the Trump Organization artificially inflated its property values for purposes of obtaining loans or larger compensations for easements from the government.

While Trump apparently signed off on all the false statements, his defense again will be that he was a busy guy, he depended on his lawyers, accountants and appraisers to get it right, and he had no specific knowledge or intent to commit fraud.

Trump keeps few if any notes and famously never uses personal computers or emails, so once again there is no strong paper trail that would independently show that Trump knew about the fraud and approved of it. No one inside his organization has flipped on him as far as we are aware.

And last week, Trump pled the Fifth in response to questioning by James in her civil case for tax fraud. He did so 440 times rather than risk saying anything that could tie him to the alleged crimes.

Other prosecutors no doubt are watching and learning from the difficulties the teams in New York have faced. But running what is essentially a criminal syndicate is far different than running the U.S. government.

For starters, Trump has had trouble keeping quiet those who were with him in the room and heard him plot the coup, and many of those folks, especially the lawyers, were prolific note-takers. (For all his attempts to destroy documentary records of meetings, many still survived the White House toilets, fireplaces, burn bags, and hand shredding.)

That’s why news of a Department of Justice grand jury subpoena to the National Archives, reported by The New York Times only yesterday despite it having been issued in May, is so noteworthy.

That subpoena sought presidential records including diaries, calendars, entries and notes that could be used to build a case, beginning with:

- who was where with Trump

- when was it

- what were they doing.

In its developing criminal investigation, the DoJ has the advantage of building on the prior work of the January 6 Committee, which had meticulously pieced together a thorough timeline and documentary trail for the Department to follow.

It may also be far easier to find government witnesses willing to testify against the former President.

While Allen Weisselberg steadfastly has refused to turn directly on his benefactor, with whom he has decades of history and who might in fact be in fear of what Trump could have done to him, it is far less likely that those who were only in Trump’s political orbit for only a short time will fall similarly on their swords. Aides and advisers from Mark Meadows to John Eastman are likely watching closely as Trump’s legal woes build, wondering if they should abandon ship early and possibly get a better deal than those who hold out.

There are also signs that some of Trump’s staunchest allies want to distance themselves promptly. Yesterday, conspiracy peddler Alex Jones of Infowars declared that he is now supporting Ron DeSantis, and not Trump, for 2024. Fox News’ Laura Ingraham mused on a podcast that “voters might say it’s time to turn the page on Trump.”

Former Vice President Mike Pence told a crowd in New Hampshire that he would “consider” appearing before the January 6 Committee if asked. Trump’s lawyer Rudy Giuliani testified for some six hours before a Georgia grand jury investigating election interference in that state helmed by Trump.

And even Russian experts publicly opined this week that Trump has too much baggage and that “Number Two” Ron DeSantis might be a better bet for the GOP.

Sometimes dams hold, as we appear to be seeing happen within the Trump Organization. But sometimes they start to crack, as we may finally be seeing with the former White House administration and its allies.

Trump may know from years of experience how to hide his involvement in fraudulent financial schemes, but he appears to have been less successful when it comes to washing his hands clean of White House conspiracies.

Up against persistent National Archivists, the power of the January 6 Committee, the weight of the Department of Justice, and the doggedly determined Fulton County Georgia District Attorney, Trump’s chances of pulling off a successful legal escape for his governmental crimes—though still a real possibility—seem far lower than he has ever faced for his business crimes.

Awkward Pena GIF by Luis Ricardo

Awkward Pena GIF by Luis Ricardo  Community Facebook GIF by Social Media Tools

Community Facebook GIF by Social Media Tools  Angry Good News GIF

Angry Good News GIF

Angry Cry Baby GIF by Maryanne Chisholm - MCArtist

Angry Cry Baby GIF by Maryanne Chisholm - MCArtist

@adriana.kms/TikTok

@adriana.kms/TikTok @mossmouse/TikTok

@mossmouse/TikTok @im.key05/TikTok

@im.key05/TikTok @biontrtwff101/TikTok

@biontrtwff101/TikTok @likebrifr/TikTok

@likebrifr/TikTok @itsashrashel/TikTok

@itsashrashel/TikTok @ur_not_natalie/TikTok

@ur_not_natalie/TikTok @rbaileyrobertson/TikTok

@rbaileyrobertson/TikTok @xo.promisenat20/TikTok

@xo.promisenat20/TikTok @weelittlelandonorris/TikTok

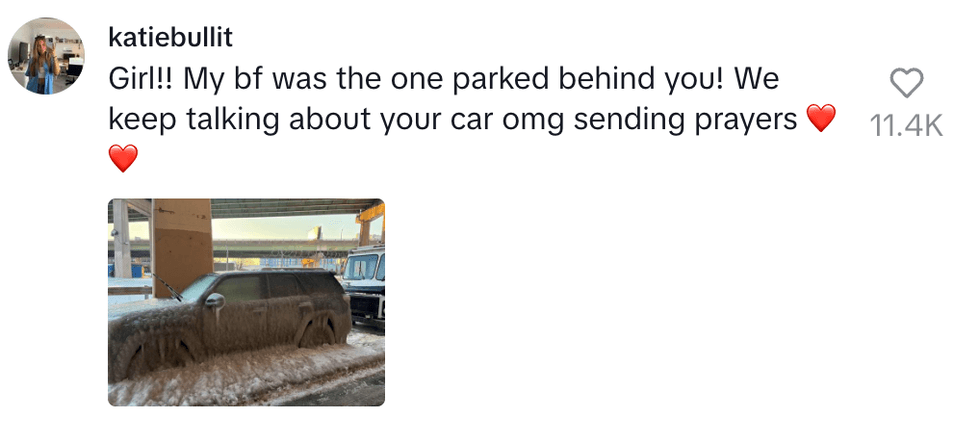

@weelittlelandonorris/TikTok @katiebullit/TikTok

@katiebullit/TikTok @rube59815/TikTok

@rube59815/TikTok

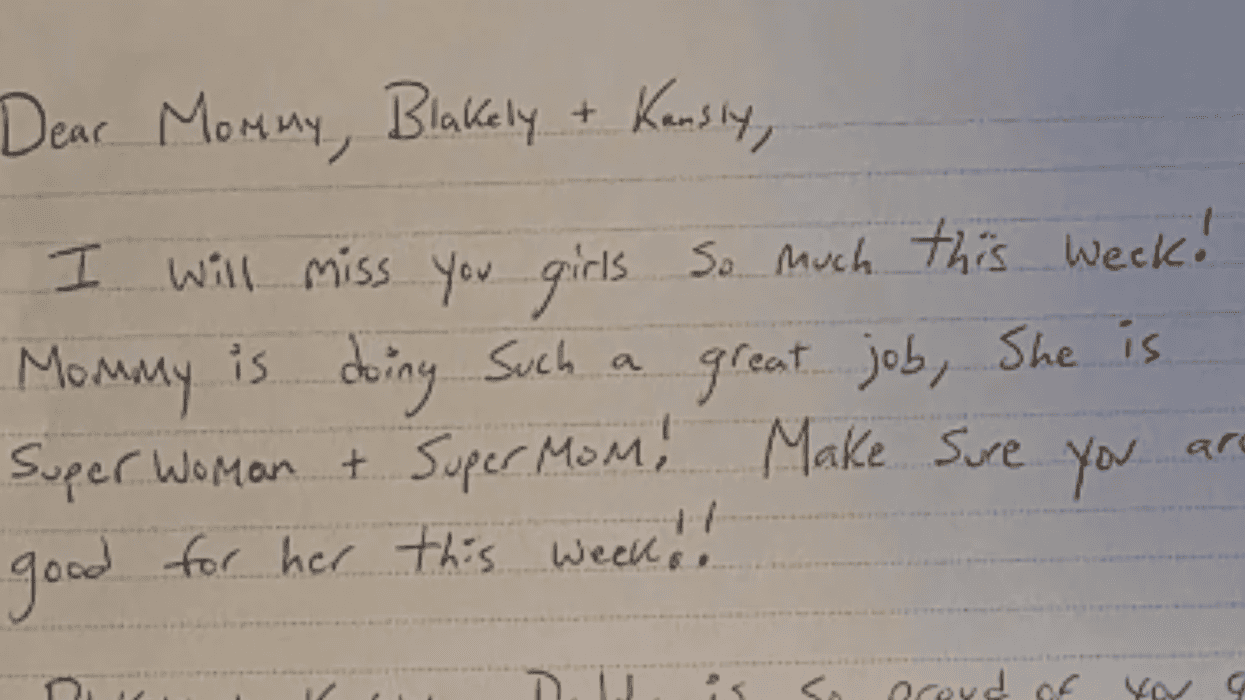

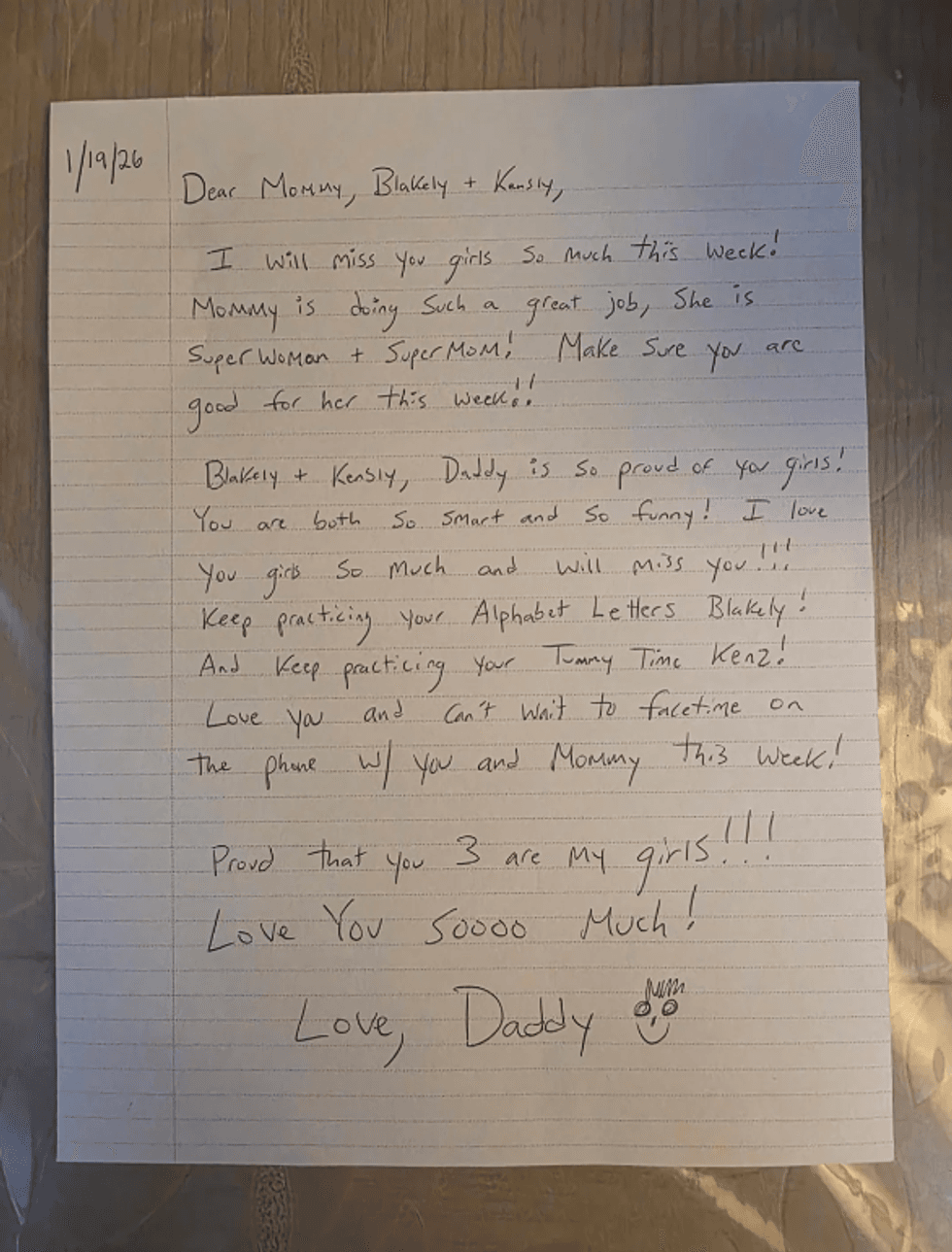

u/Fit_Bowl_7313/Reddit

u/Fit_Bowl_7313/Reddit

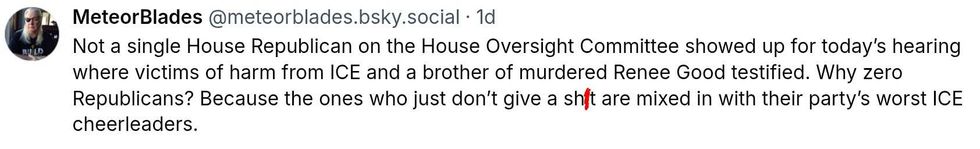

@meteorblades/Bluesky

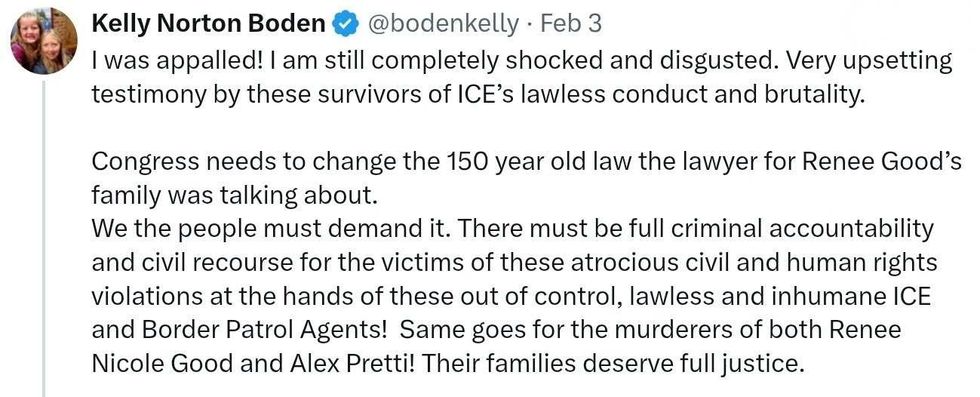

@meteorblades/Bluesky @bodenkelly/X

@bodenkelly/X