We all want to leave a legacy. Whether that takes the form of creative works, breakthrough discoveries, children, or other actions, we all want a way to show we were here. For nearly all of us, though, that legacy will be a literal ton of plastic garbage. Every disposable cup, straw, food wrapper, plastic bag, toy and bottle we use adds up to a lot of trash—9 billion tons of it and counting. The vast majority is still here, and will still be here thousands of years after we are gone. It is our most lasting legacy.

It is a problem of monumental proportions, and a solution is urgently needed. Perhaps science has discovered one. At a recycling plant in Japan in 2016, researchers discovered a microbe that has evolved to eat plastic.

The new species of bacteria, Ideonella sakaiensis, breaks down PET, a common plastic used in clothing and water bottles, and link to the PET with tendril-like threads. They then use two enzymes sequentially to break down PET into terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol, the two substances from which it is manufactured and that are not harmful to the environment. The bacteria then digest both substances.

The Kyoto researchers identified the gene in the bacteria’s DNA that is responsible for the PET-digesting enzyme. In experiments, they were able to manufacture more of the enzyme and demonstrated that PET could be broken down with the enzyme alone.

The discovery isn’t ready for practical use in recycling yet: In experiments, the bacterium could break down a thin film of PET the size of a thumbnail in a little over six weeks. Unfortunately, our rate of plastic production far outpaces that rate of decomposition. However, with a little genetic modification, there is a possibility. It took 70 years for this bacterium to naturally evolve to clean up our mess (plastic were first created in the 1940s). With a little help from science, the next iteration could be speedier.

“We have to improve the bacterium to make it more powerful, and genetic engineering might be applicable here,” says Kohei Oda of Kyoto Institute of Technology in Japan, whose team made the discovery. One possibility: Scientists could transfer the genes into a faster growing bacterium like Escherichia coli, says Uwe Bornscheuer of Greifswald University in Germany.

What’s the hurry? Our plastic addiction is choking, poisoning and smothering our fellow creatures. When a young sperm whale that beached itself in Murcia, Spain, in April 2018 was opened up, scientists found 64 pounds of plastic trash, including 30 plastic bags. Its stomach had ruptured, unable to digest the garbage. A few weeks later, a pilot whale full of plastic washed up in Thailand. "The presence of plastic in the ocean and oceans is one of the greatest threats to the conservation of wildlife throughout the world, as many animals are trapped in the trash or ingest large quantities of plastics that end up causing their death," said Murcia's general director of environment, Consuelo Rosauro.

In Brooklyn, activists are calling for a ban on fishing after a locally famous great horned owl that lived in Prospect Park died, tangled in plastic fishing line that cut into its legs. Anglers leave plastic fishing line on beaches and lakeshores, where it becomes a hazard for wildlife. In Colorado, it’s become such a problem that one state park has installed six special trash bins for the line.

Microplastics — tiny, microscopic bits of plastic from fleece clothing, cosmetics, and partially decomposed trash — are now appearing in agricultural soil, fish and even beer. The microtrash affects growth, reproduction and survival of aquatic creatures.

In the US, only 9 percent of plastic garbage gets recycled, and the amount we use is rapidly escalating. "If current trends continue, the researchers predict over 13 billion tons of plastic will be discarded in landfills or in the environment by 2050," the American Association for the Advancement of Science said in a statement accompanying a study on plastic garbage.

In addition to the Kyota team’s discovery, a couple other organisms can also digest plastics. A plastic-eating fungus called Pestalotiopsis microspora can consume a type of plastic called polyurethane. An insect known as the wax moth can eat polyethylene, which accounts for 40 percent of plastics. They started out eating beeswax, but the skill transferred.

“Wax is a complex mixture of molecules, but the basic bond in polyethylene, the carbon-carbon bond, is there as well,” said Federica Bertocchini, a biologist at Spain’s Institute of Biomedicine & Biotechnology of Cantabria. “The wax worm evolved a mechanism to break this bond.”

But again, time is of the essence, and our rate of figuratively consuming plastics far outpaces the bacteria’s ability to literally consume them. Unless humans can find a way to use less plastic, we will have to find a way to speed up these organisms’ appetites. If it can be done on a massive scale, the researchers who came up with this discovery will leave a legacy that will help every living thing on the planet.

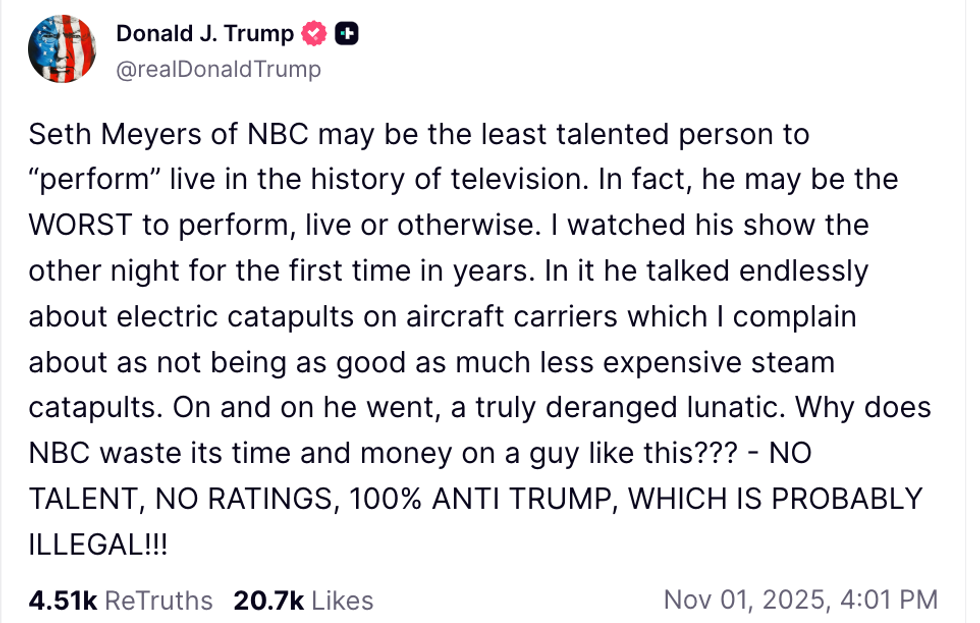

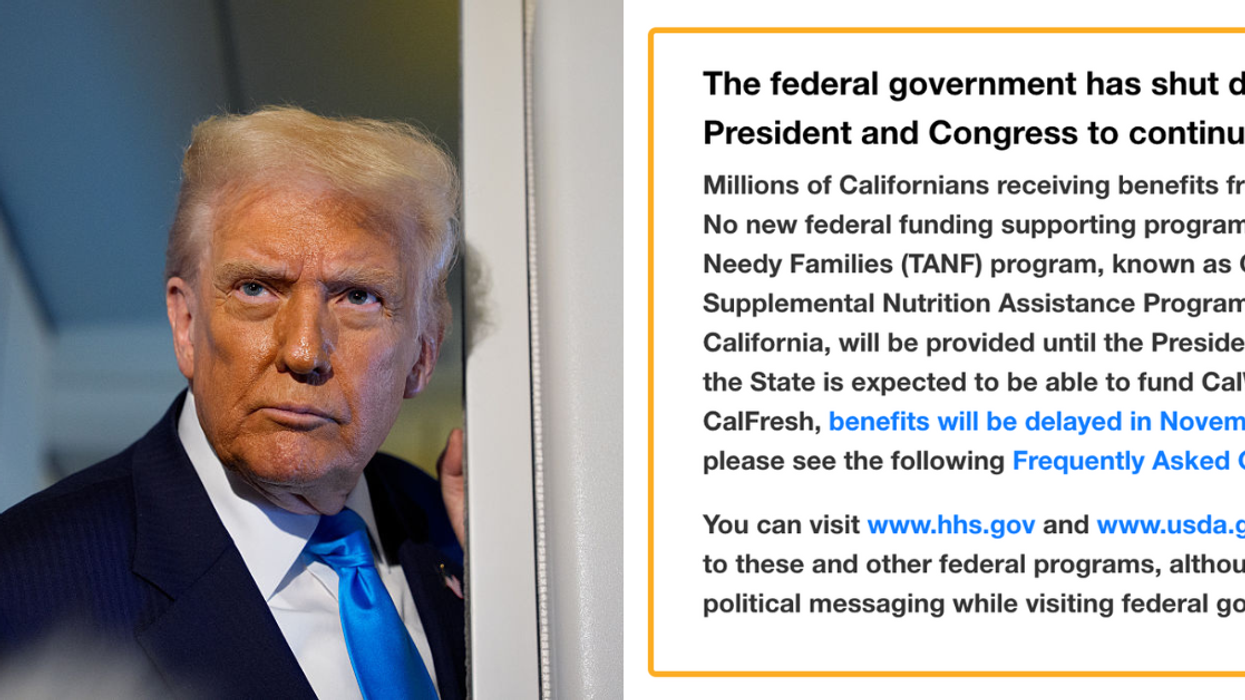

@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social

@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social

@rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok @rootednjoyy/TikTok

@rootednjoyy/TikTok

@BarryMu38294164/X

@BarryMu38294164/X