Despite efforts to pressure electoral college members to switch their votes to honor the popular vote count, electors chose to seat Donald Trump, a result Congress will ratify next month. While efforts were fervent, they were always unlikely to persuade enough electors to switch their votes. In fact, there has never been a revolt by the College in its entire history.

The New York Times issued a widely circulated op-ed yesterday favoring an end to the electoral college. Although Trump, it wrote, “won under the rules… the rules should change so that a presidential election reflects the will of Americans and promotes a more participatory democracy.” The electoral college, it wrote, “is more than just a vestige of the founding era; it is a living symbol of America’s original sin.” Through the infamous three-fifths compromise, slaves counted towards the electoral college votes of each state, but they were not allowed to vote. Thus, while a direct popular vote would have placed the Southern states at a disadvantage, the electoral college advantaged them. In large part because of this, seven out of eight of the first U.S. Presidents hailed from a Southern slave-holding state, Virginia, which commanded a massive number of electoral votes.

There have been many calls for an end to the electoral college. But yesterday’s editorial was noteworthy for its support of a specific mechanism to get around the electoral college: The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact.

As the Times noted, there is a very serious effort underway to effectively undo the electoral college that would not require so-called “faithless” electors or an actual Constitutional Amendment. For some time, critics (now joined by million of petitioners) have argued that the Electoral College is an archaic institution that leaves America out of touch with modern democracies, where the national popular vote winner is always simply the winner. But getting a Constitutional Amendment approved has always seemed highly unlikely. After all, the three-fourth majority of states needing to ratify it include many that would lose power without the college.

Enter the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, which comprises a practical way around this and already has gone more than half the way towards going into effect. Its strategy is simple: convince states with at least 270 of the electoral college votes to agree that their electors will vote for the candidate who won the popular vote, no matter who won the state’s electoral college votes.

According to the initiative’s website, the electoral college’s shortcomings “stem from state winner-take-all statutes (i.e., state laws that award all of a state’s electoral votes to the candidate receiving the most popular votes in each separate state). Because of these state winner-take-all statutes, presidential candidates have no reason to pay attention to the issues of concern to voters in states where the statewide outcome is a foregone conclusion.” For example, two-thirds of the 2012 general-election campaign events (176 of 253), were in just four states––Ohio, Florida, Virginia and Iowa. “State winner-take-all statutes adversely affect governance,” the site continues. "‘Battleground’ states receive 7% more federal grants than “spectator” states, twice as many presidential disaster declarations, more Superfund enforcement exemptions, and more No Child Left Behind law exemptions.”

Those spearheading the project stress that the NPV would not take effect “until enacted by by states possessing a majority

of the electoral votes—that is, enough to elect a President (270 of 538).” The winner under the compact would be the candidate who received the most popular votes from each state (and the District of Columbia). The winner of the national popular vote would receive all of the electoral votes of the enacting states.

Defenders of the Electoral College note that if the popular vote were all that mattered, politicians would only go after vote-rich centers in the cities and ignore rural voters’ concerns because they would gain few votes. Proponents counter that currently that’s already the case, with reliably red states getting little to no visits or efforts by candidates. As things stand, a handful of battleground states gain all of the attention and nearly always hold the key to the election. As the Times notes, the votes of Republicans in San Francisco and Democrats in Corpus Christi are “currently worthless.” Almost 138 million people voted on Election Day, “but Mr. Trump secured his Electoral College victory thanks to fewer than 80,000 votes across three states: Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.”

The president-elect delivers his acceptance speech on Election Night. (Credit: Source.)

The president-elect delivers his acceptance speech on Election Night. (Credit: Source.)

The Times has opposed the electoral college for nearly 80 years. In an editorial dated November 9, 1936, the Editorial Board decried the results of the presidential election between Franklin Delano Roosevelt––then running for his second term––and Kansas Governor Alf Landon, a political moderate: “Never before in our political history did the Electoral College appear, on casual inspection, to be so obsolete as in this year's Presidential election,” they wrote. “Governor LANDON received in the neighborhood of 17,000,000 votes, but came out with only eight electoral votes. This disparity seems gross and grotesque.” (The 1936 presidential election is widely considered the most lopsided of all presidential elections in terms of electoral votes.)

“Many Republicans have endorsed doing away with the Electoral College, including Mr. Trump himself, in 2012,” the Editorial Board concludes. “Maybe that’s why he keeps claiming falsely that he won the popular vote, or why more than half of Republicans now seem to believe he did. For most reasonable people, it’s hard to understand why the loser of the popular vote should wind up running the country.”

The Benny Show

The Benny Show

@neilforreal/Bluesky

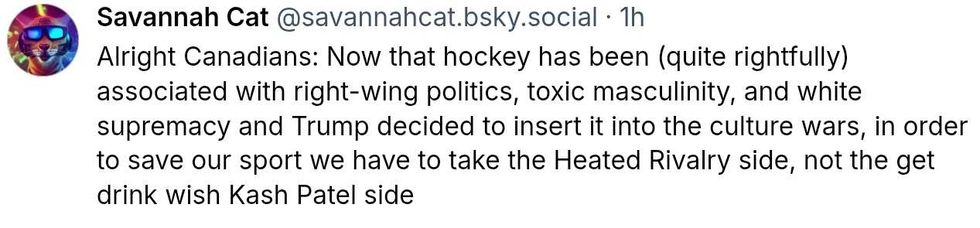

@neilforreal/Bluesky @savannahcat/Bluesky

@savannahcat/Bluesky @qadishtujessica.inanna.app

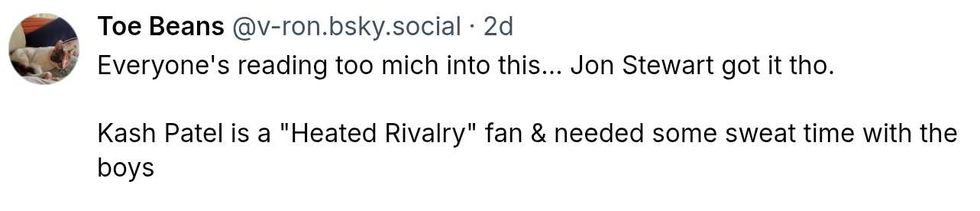

@qadishtujessica.inanna.app @v-ron/Bluesky

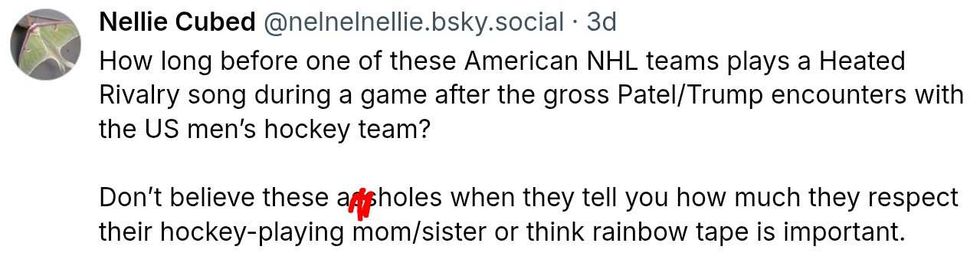

@v-ron/Bluesky @nelnelnellie/Bluesky

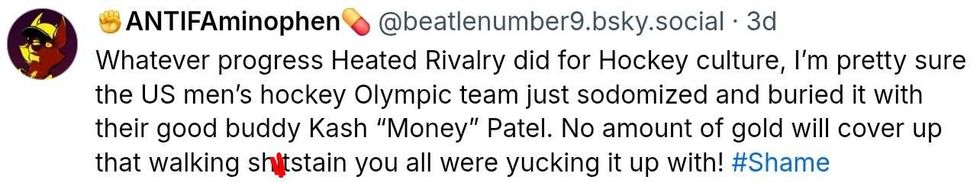

@nelnelnellie/Bluesky @beatlenumber9/Bluesky

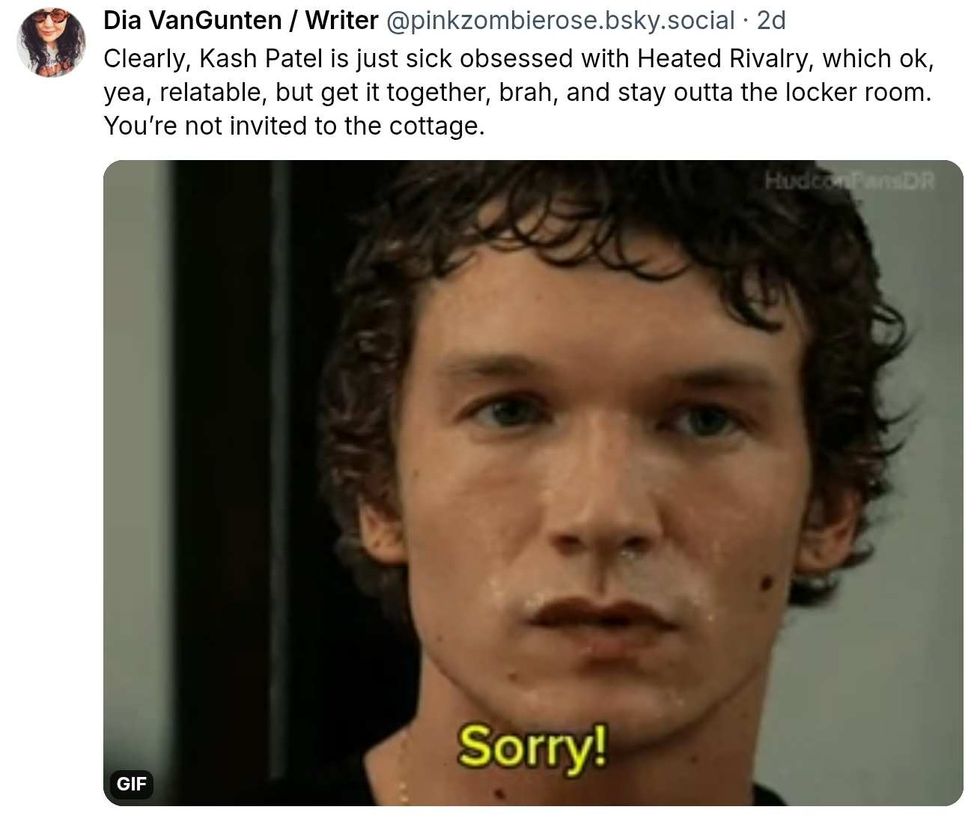

@beatlenumber9/Bluesky @pinkzombierose/Bluesky

@pinkzombierose/Bluesky

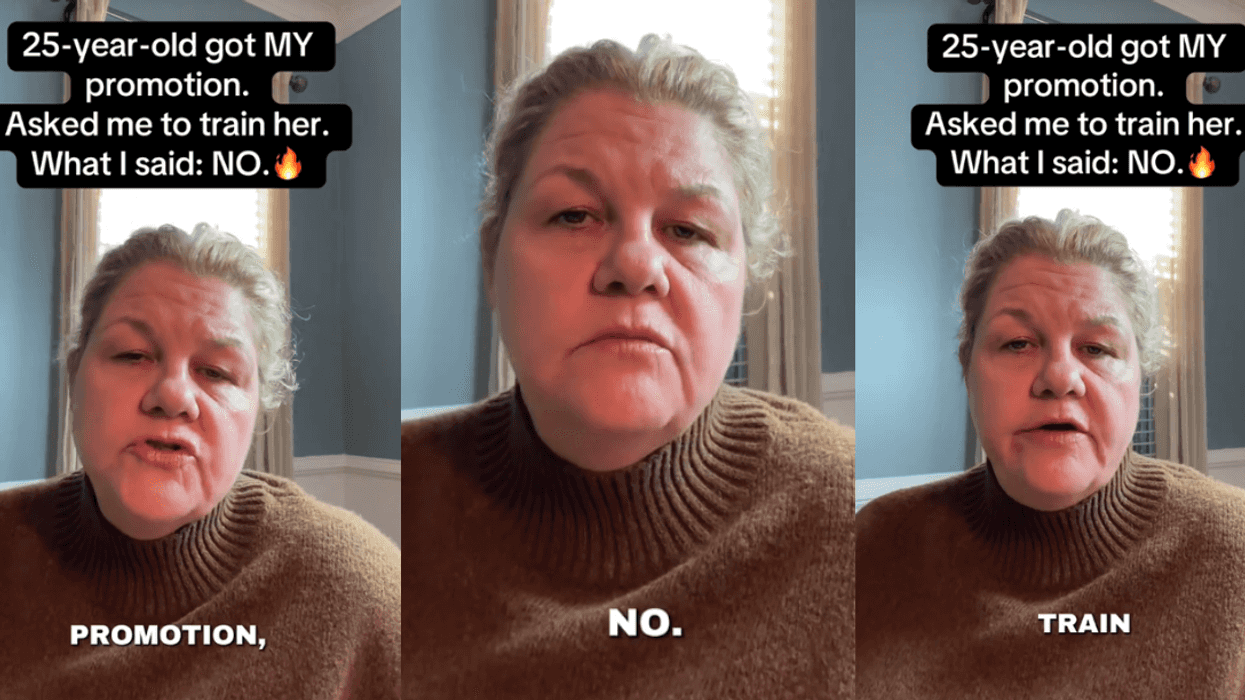

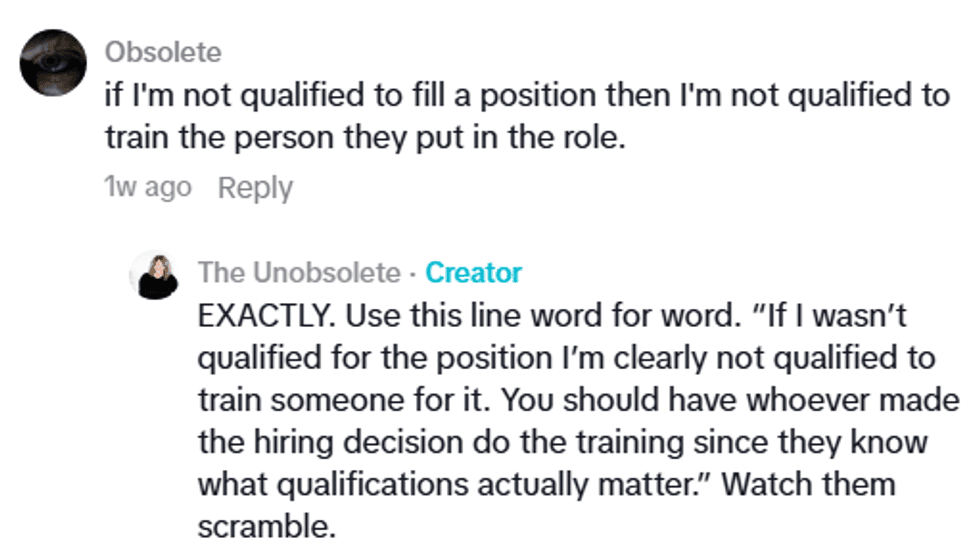

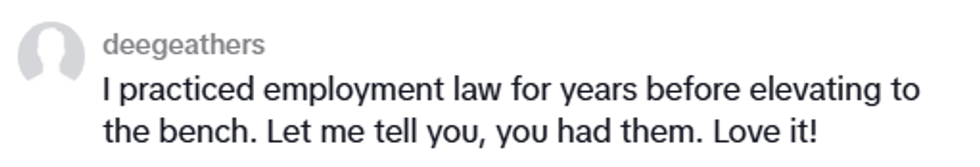

@theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok @theunobsolete/TikTok

@theunobsolete/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok @laysuperstar/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok @laysuperstar/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok @laysuperstar/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok @laysuperstar/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok @laysuperstar/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok @laysuperstar/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok @laysuperstar/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok @laysuperstar/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok @laysuperstar/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok @laysuperstar/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok @laysuperstar/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok @laysuperstar/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok @laysuperstar/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok @laysuperstar/TikTok

@laysuperstar/TikTok