For perhaps the first time, patients suffering from Huntington’s disease have cause for hope. A recent trial conducted by researchers at University College London (UCL) indicates that an experimental drug may significantly suppress a mutated gene related to Huntington’s devastating degenerative effects.

It is estimated that about 30,000 people in the United States and 8,500 people in the UK currently suffer from Huntington's. The disease, which some patients describe as a mix of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and ALS, is responsible for a dizzying array of symptoms. Patients first experience severe mood swings and depression, then face ever-worsening dementia and a gradual loss of motor control that ends in paralysis; the majority die about 10 to 20 years following its onset.

“Most of our patients know what’s in their future,” said Ed Wild, a scientist who helped conduct UCL’s trial.

The disorder typically surfaces when patients are in their 30s or 40s, at which point those with children may unwittingly have passed the genetic mutation on to the next generation. This mutation, known as the huntingtin gene, triggers the creation of toxic huntingtin protein, which builds up in the brain and leads to mass cell death responsible for patients’ physical and mental decay.

Ionis-HTTRx, the drug featured in UCL’s trial, functions by essentially silencing the mutated huntingtin gene. Typically, the gene instructs messenger molecules to infiltrate cells and produce the dangerous protein. However, the trial provided the first evidence to suggest this protein creation process could be stopped in its tracks.

Forty-six men and women in early stages of Huntington’s received this revolutionary treatment at the Leonard Wolfson Experimental Neurology Centre at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London. Some participants received placebos, while others received an injection of the drug directly into their spines.

Initial results showed that, not only were patients who received the infusion able to tolerate the drug with no notable side effects but that their levels of huntingtin protein were significantly lower following treatment. This suggests that the drug successfully intercepted messenger molecules, preventing them from entering brain cells and crucially lowering huntingtin protein levels as a result.

Existing treatments for Huntington’s help manage symptoms but can’t prevent or reverse the disease’s progress, making these new results particularly powerful and unprecedented. While researchers caution that Ionis-HTTRx is not a cure, and note that this trial had too small a sample size and did not run for a long enough period to be deemed conclusive, many are hopeful that this treatment will make a huge impact in patients’ quality of life.

Said Professor Sarah Tabrizi, the study’s lead researcher and director of the Huntington's Disease Centre at UCL: "I've been seeing patients in clinic for nearly 20 years, I've seen many of my patients over that time die. For the first time we have the potential, we have the hope, of a therapy that one day may slow or prevent Huntington's disease. This is of groundbreaking importance for patients and families."

Professor John Hardy, a renowned Alzheimer’s researcher who was not affiliated with this study, further emphasized the trial’s importance: "I really think this is, potentially, the biggest breakthrough in neurodegenerative disease in the past 50 years. That sounds like hyperbole — in a year I might be embarrassed by saying that — but that's how I feel at the moment."

Hardy suggested similar protein-suppressing drugs could potentially yield positive results for Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases: for instance, proteins amyloid and tau are linked to dementia, while synuclein is associated with Parkinson’s.

Ionis Pharmeuticals, the company that developed Ionis-HTTRx, said the drug "substantially exceeded" their expectations. Following this trial, Swiss healthcare behemoth Roche, which licensed rights to use the drug at the cost of $45 million, announced plans to conduct further trials before making the drug widely available to patients.

Tabrizi feels confident that, after more conclusive, long-term studies, the drug could one day be used to stave off Huntington’s altogether, stopping initial symptoms before they occur. “They may just need a pulse every three to four months,” she said. “One day we want to prevent the disease.”

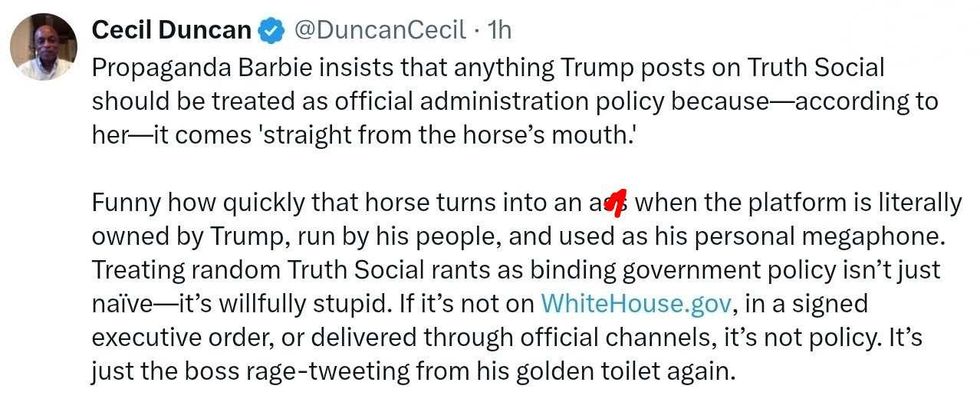

@DuncanCecil/X

@DuncanCecil/X @@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social

@@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social @89toothdoc/X

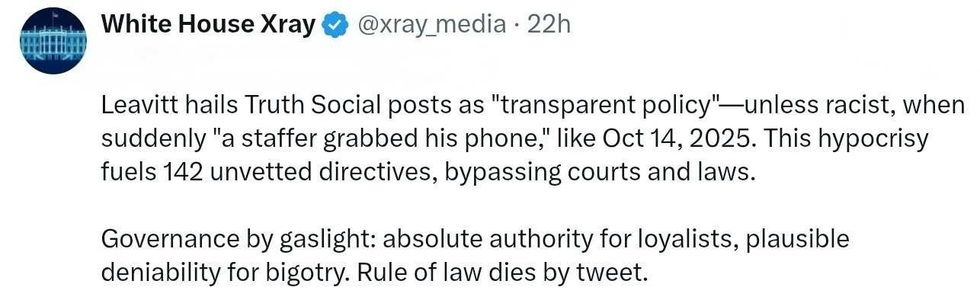

@89toothdoc/X @xray_media/X

@xray_media/X @CHRISTI12512382/X

@CHRISTI12512382/X

@sza/Instagram

@sza/Instagram @laylanelli/Instagram

@laylanelli/Instagram @itssharisma/Instagram

@itssharisma/Instagram @k8ydid99/Instagram

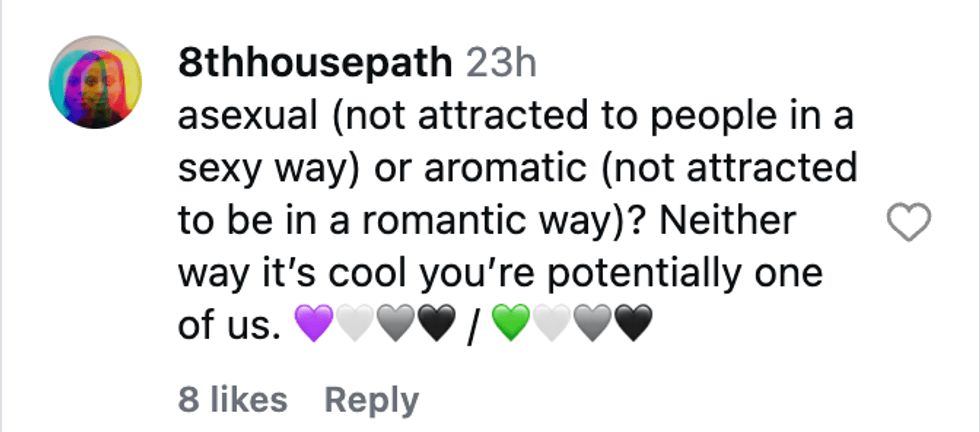

@k8ydid99/Instagram @8thhousepath/Instagram

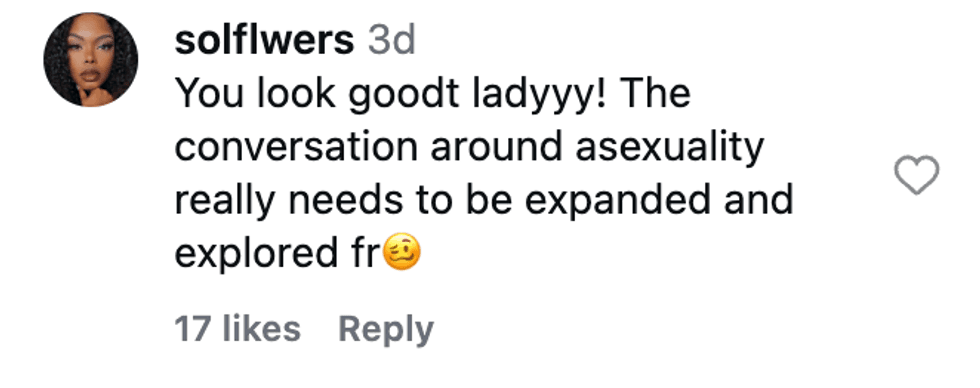

@8thhousepath/Instagram @solflwers/Instagram

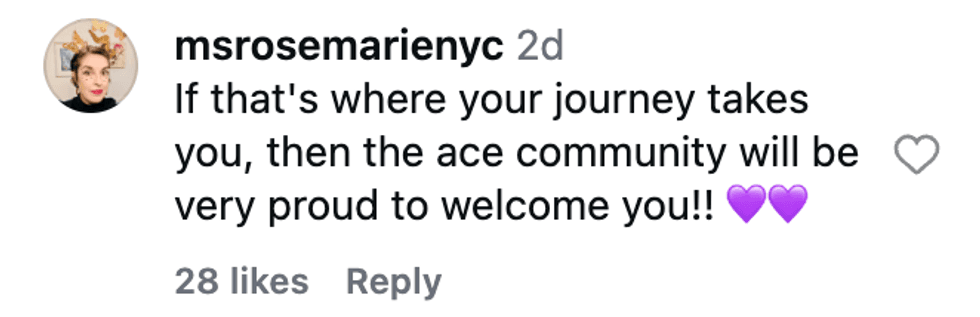

@solflwers/Instagram @msrosemarienyc/Instagram

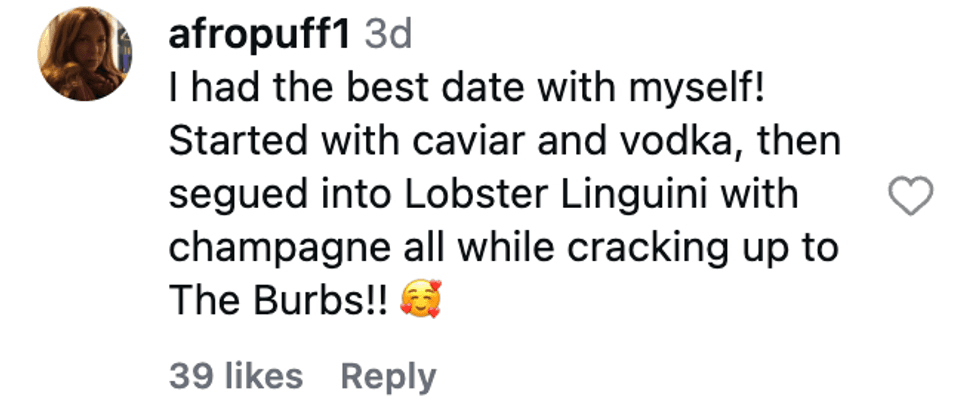

@msrosemarienyc/Instagram @afropuff1/Instagram

@afropuff1/Instagram @jamelahjaye/Instagram

@jamelahjaye/Instagram @razmatazmazzz/Instagram

@razmatazmazzz/Instagram @sinead_catherine_/Instagram

@sinead_catherine_/Instagram @popscxii/Instagram

@popscxii/Instagram