The clock has been the enemy lately for state and local investigators in New York who have been tackling what New York Attorney General Letitia James described as the “Russian nesting doll” of the Trump Organization’s finances. While state investigators face the expiration of the statute of limitations to bring a civil suit against the Trumps and their company for fraudulent financial statements, the authority of the Manhattan District Attorney’s grand jury investigating possible criminal charges for that fraud expired this week. And stonewalling by Trump reached such a crescendo lately that a judge imposed sanctions of $10,000 per day for his non-compliance with a request for responsive documents, raising questions over whether James ultimately will have all the evidence she needs to bring her civil suit.

And yet. Just as the likelihood of criminal charges for financial statement fraud has dropped precipitously within the Manhattan DA’s office, to the disbelief and howls of many, a new and unforced error by Donald Trump himself may have given life to the chances that he will join his CFO Allen Weisselberg and the Trump Organization in being charged with tax fraud. Let’s unpack.

The state of the New York AG Investigation

There are three important things to keep clear about James’s investigation.

First, it is a civil matter, so we are looking at monetary fines, perhaps big ones, and even the possibility that the Trump Organization could lose its corporate status granted long ago by the state. But no one is going to jail in this case, even if a complaint is brought. That said, James scored a major win when Trump’s longtime accountants at Mazars USA walked away from 10 years of financial statements, saying that in part due to the investigation, it could no longer stand by them.

Second, there are statutes of limitations for fraud that will soon expire. These kinds of laws generally prevent the filing of complaints about events that took place so long ago that evidence (like witness recollections) becomes unreliable. The parties here agreed to a “tolling” of the statute, meaning for some period of time, by agreement, the clock was not ticking. But that period is nearly up, and that means James had better file something soon. She is confident, however, that her office will soon conclude its investigation and be in a position to make a decision as to whether to proceed with a civil suit. Most observers believe one will be filed.

Third, while Trump plays games by refusing to cooperate with the investigation, the possible consequences of that go beyond the $10,000 per day fine he is now accumulating for his contempt of court. His behavior could be taken into consideration in any possible court case, with adverse inferences drawn for why he would rather face a contempt ruling and pay a fine than cooperate. This is similar to how pleading the Fifth Amendment can’t be used against defendants in a criminal proceeding, but in a civil one it can be cited as evidence that they have something to hide.

The State of the Manhattan DA cases

Financial fraud cases are difficult to prove, especially where the boss man doesn’t leave a paper trail and those below him who do his bidding are unwilling to flip. That difficulty level is the most likely reason the new District Attorney for Manhattan, Alvin Bragg, expressed doubts to the lead prosecutors over the strength of their case for financial statement fraud, much to their frustration. After all, Trump can still simply say he relied upon his CFO and his accountants and only signed where they told him to sign. To contradict that and prove fraud beyond a reasonable doubt, you need solid witnesses and evidence.

But the fraudulent financial statements case isn’t the only one on the docket against Trump in Manhattan. There is also the pending criminal case for more straightforward tax fraud, which has already snagged indictments of CFO Weisselberg and the Trump Organization itself. That case involves the use by the company of what amounts to two sets of books so that it could provide fancy perks (such as luxury apartments, expensive cars, and private tuition for their children) to high-level executives in the Trump Organization so that they and the company could avoid tax liability. That conduct, if proven, is very much illegal. Anyone who participated in that could also be charged with conspiracy if they could be shown to be in on the plan.

But once again, in that case prosecutors face the daunting task of getting Trump’s underlings to flip on him. Otherwise, Trump could simply plead ignorance of the details and wash his hands of any responsibility or authority. To date, prosecutors have been unable to crack Weisselberg, whose trial is set for later this year. So who else would ever come forward and say that Trump himself approved these illegal perks and oversaw the payments to top Trump executives?

The answer may be Donald Trump himself. In a court case unrelated to any of this, in which the plaintiffs sued the Trump Organization for the way its security guards manhandled protestors back in 2015, Donald Trump was finally ordered to testify and did so in October of 2021. In that deposition, Trump repeatedly asserted that he—and only he—oversaw the way the company’s Chief Operating Officer Matthew Calamari, Sr. was paid for his work. “It would be me,” Trump said multiple times when asked who had authority over Calamari’s pay. Excerpts from that deposition were only recently filed in court as part of that other lawsuit.

It may have been a bad mistake by Trump to admit that authority. In the Manhattan DA’s ongoing tax fraud case, Calamari Sr. is alleged to have received the very kind of illegal, tax-evading perks that landed Weisselberg with an indictment. If Trump himself, and not an intermediary like Weisselberg, had authority over Calamari’s pay, that would tie Trump to direct knowledge and participation in the scheme to avoid taxes by paying under the table, off-the-books benefits.

There remains a question over whether this testimony can go before the grand jury so that it might consider a new indictment against Trump himself. As an “out of court statement,” the testimony is considered hearsay, and New York state is unlike other jurisdictions in that the rules of evidence, including hearsay, apply even in grand jury settings. Prosecutors could seek to get around this by arguing that the statement is an exception to the hearsay rule, e.g. because it is a statement by a party against his own financial or criminal interest, but that would have to be decided by a judge.

It’s unclear why, when their client was faced with the key question of whether he had authority over the pay structure of one of his top executives—the very question at the heart of the Manhattan DA’s active tax fraud case—Trump’s attorneys would not have immediately advised him to assert his privilege against self-incrimination. This was only a civil suit for damages, after all, and it shouldn’t result in such a disastrous admission. It’s early to tell, but there is a thread here that Manhattan prosecutors now may wish to pull, especially as that office faces renewed criticism for having backed off of its other case on grounds there was not sufficient evidence to charge Trump.

How ironic but fitting it would be should Trump ultimately face criminal charges for tax fraud because he didn’t keep his mouth shut when it truly mattered.

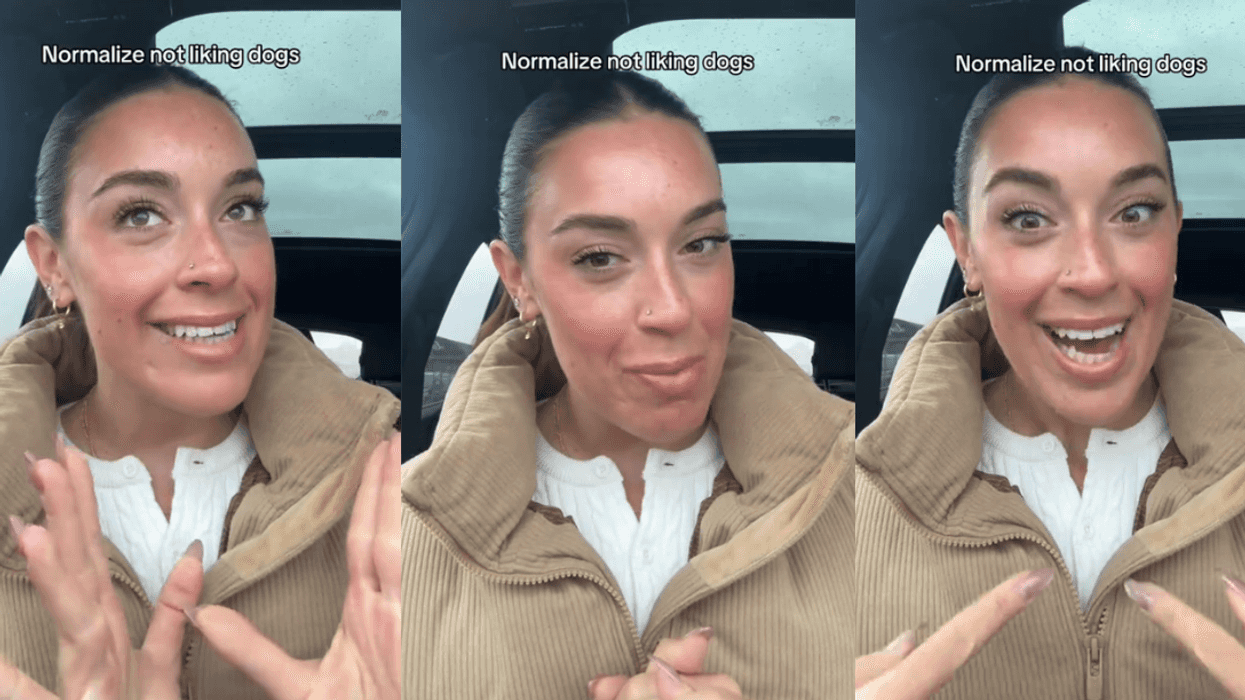

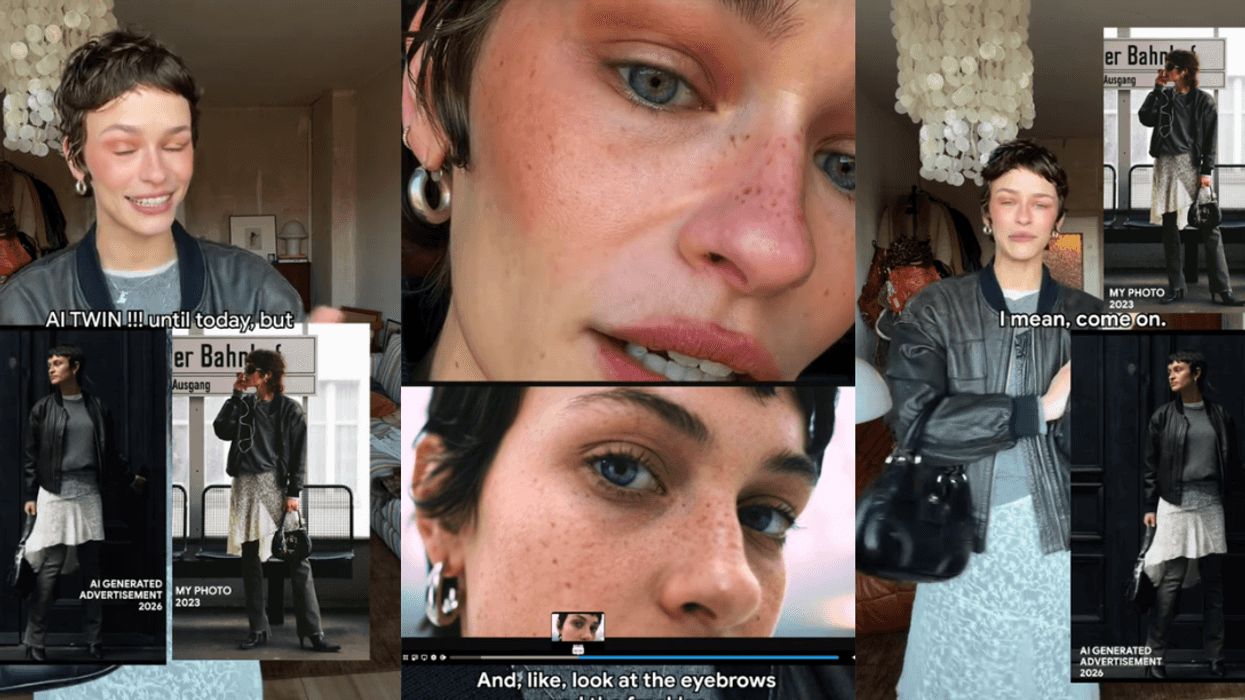

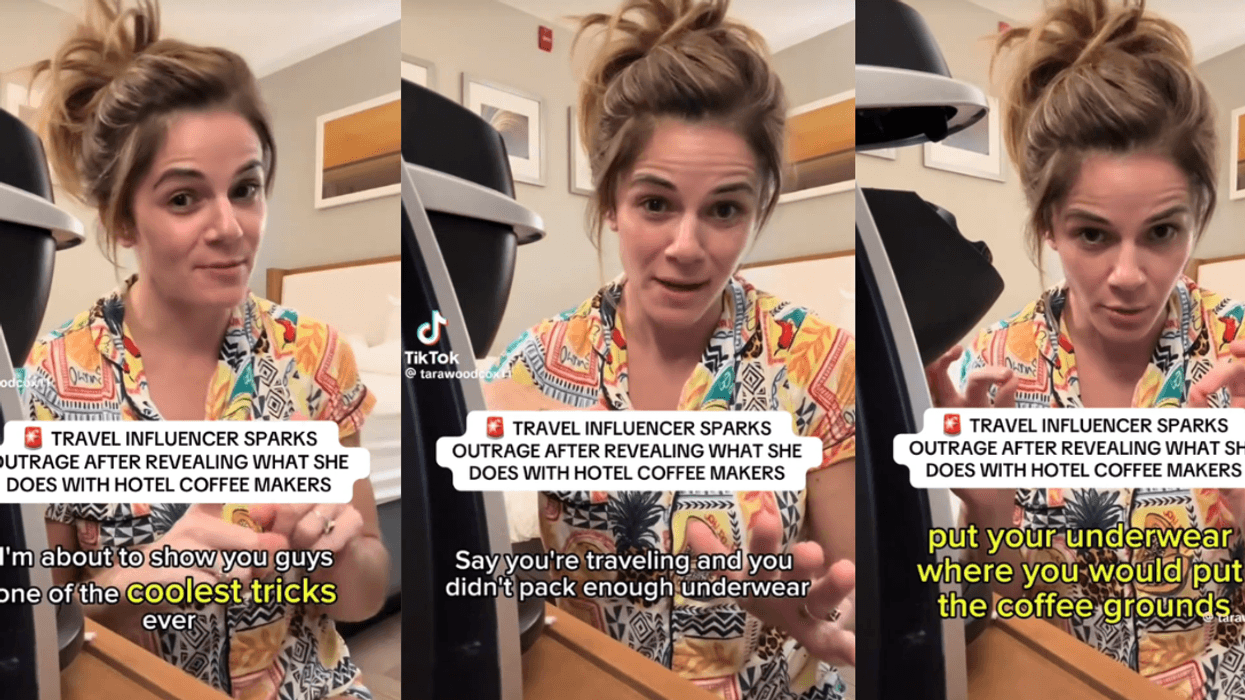

@madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok

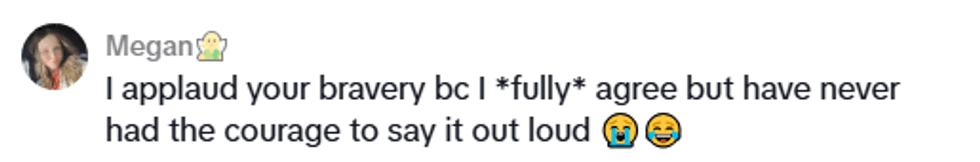

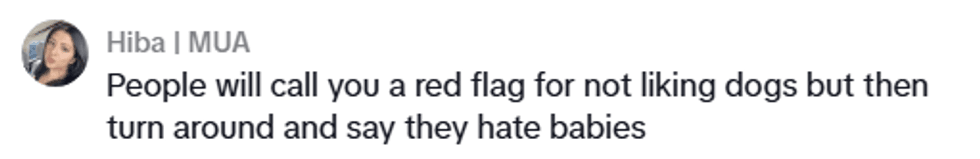

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok