Does censoring free speech come at the cost of public health?

By now, it is well understood that the Trump administration has curbed seven words from appearing in official documents prepared by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). According to a report by The Washington Post, the newly-limited words and terms are: diversity, entitlement, evidence-based, fetus, science-based, transgender and vulnerable.

However, the CDC explains no words are actually banned. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention director Dr. Brenda Fitzgerald responded to the report, “I want to assure there are no banned words at CDC.”

She went on, “CDC has a long-standing history of making public health and budget decisions that are based on the best available science and data and for the benefit of all people—and we will continue to do so.”

In a follow-up report, The New York Times cited a few CDC officials who referred to the move as a maneuver to help secure Republican approval of the 2019 budget via the elimination of certain words and phrases.

Whether it is ultimately political and ideological, or a measure by bureaucrats to save certain projects from budget cuts, terms like science-based and evidence-based are seeing their replacements in phrases like, “CDC bases its recommendations on science in consideration with community standards and wishes.”

The concern is that hazy language, especially in the medical field, can ultimately make the difference between a patient living and dying. This is because such language is not a dependable basis for making specific and patient-tailored prognoses and diagnoses.

The terms thus far are only successfully banned in one part of the CDC, but critics of the action worry that such bureaucratic actions will cause a domino effect — like the banning of the term climate change at the Florida Department of Environmental Protection — eventually spreading the banned terms to the remainder of the organization, and by proxy, across the entire nation.

For example, the CDC is where doctors go when seeking whether or not to administer some vaccines. Back in 2000, pediatricians and family physicians learned it was safe to switch from a live polio vaccine to an inactivated one (IPV) in the United States because of the evidence the CDC had compiled, organized and posted to their website.

More specifically, practitioners knew specifically how much to administer (i.e., four doses of IPV at two months, four months, 6-18 months and a booster dose between ages four and six). This was scientifically tested and its effectiveness was proven — and none of this related to politics or bureaucracy.

Because of this testing, the IPV vaccine does not harm vulnerable populations, like children with immunodeficiency.

Such CDC-compiled information applies to many science-based fixes to health problems — not only polio — ranging from diseases like tuberculosis to food-borne illnesses to the best uses for car seats to the handling of pandemics.

Furthermore, much of the restricted language — like transgender, vulnerable, diversity and fetus — apply to particular groups of people, or those facing very specific scenarios.

When a particular group of people is neglected, those among that group do feel the discrimination. This applies to healthcare and the potential banning of words at the CDC. Groups that are marginalized tend not to participate in preventative healthcare, and may not seek help until they are quite ill.

This obviously precedes increased illnesses, death and rising healthcare costs for that group.

The present concern, with the banning or discouragement of certain words, is that the CDC recommendations will become useless to healthcare providers around the U.S. due to their vague phrasing.

For those who can decipher the new phrases that now replace the formerly unambiguous terms, these potential consequences may seem exaggerated. Some suggest that impeding the terminology is a slippery slope into authoritarianistic behavior from the U.S. government.

“The purpose of science is to search for truth, and when science is censored the truth is censored,” said Dr. Vivek Murthy, a former surgeon general, in the aforementioned report to The New York Times.

Requiring the CDC to use words and terms that are less specific than formerly permitted terms may winnow scientists and public health experts out of the agency. At the very least, an anonymous, former CDC official said to The New York Times that some staff members were unhappy because the new language implied that their work was being politicized.

Avoiding an issue does not eliminate it; shielding the American public from particular language does not make the very real meanings behind those terms vanish.

Limiting words that represent entire populations could potentially erase their experience from the public record, including the details that impact their health, the capacity to learn the unique needs of specific groups and the ability to study these groups. This sadly, but typically, hits vulnerable populations most forcefully.

Words and terms on their own may not seem so important, but their restriction could form the premise of an overhaul to the acknowledgment of specific groups of people and of science-based information. These people will still exist, but their issues could go unheard and unseen.

Weakening the American public health system — not only for the vulnerable — but for the entitled, and for all Americans, is, at minimum, a risky move.

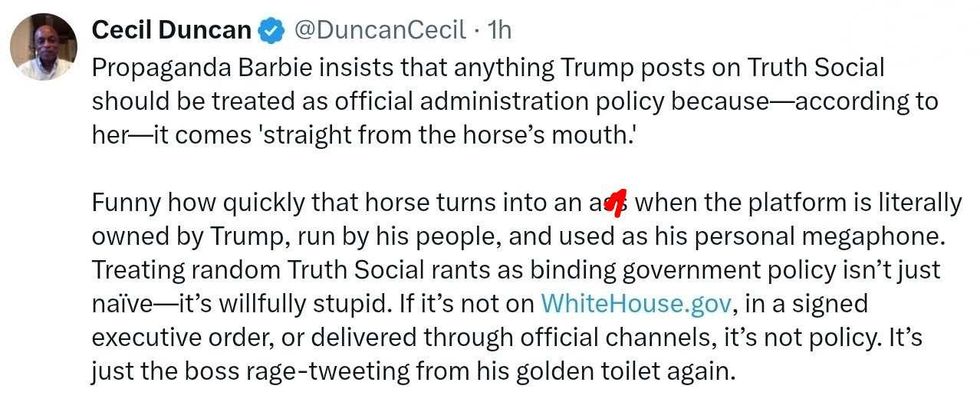

@DuncanCecil/X

@DuncanCecil/X @@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social

@@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social @89toothdoc/X

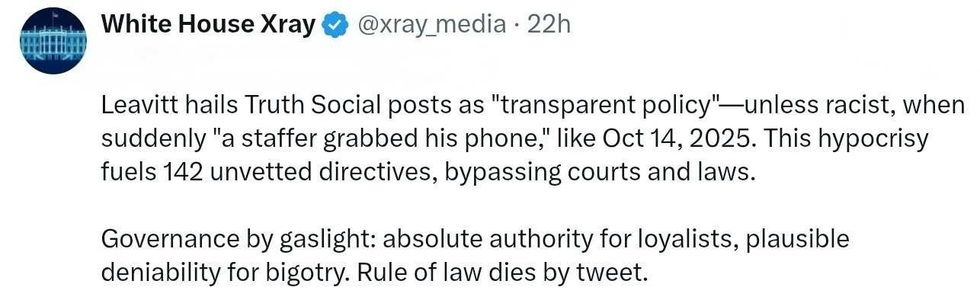

@89toothdoc/X @xray_media/X

@xray_media/X @CHRISTI12512382/X

@CHRISTI12512382/X

@sza/Instagram

@sza/Instagram @laylanelli/Instagram

@laylanelli/Instagram @itssharisma/Instagram

@itssharisma/Instagram @k8ydid99/Instagram

@k8ydid99/Instagram @8thhousepath/Instagram

@8thhousepath/Instagram @solflwers/Instagram

@solflwers/Instagram @msrosemarienyc/Instagram

@msrosemarienyc/Instagram @afropuff1/Instagram

@afropuff1/Instagram @jamelahjaye/Instagram

@jamelahjaye/Instagram @razmatazmazzz/Instagram

@razmatazmazzz/Instagram @sinead_catherine_/Instagram

@sinead_catherine_/Instagram @popscxii/Instagram

@popscxii/Instagram