For as many as 90 percent of all pregnant women, morning sickness is an expected part of the gestational experience. This period of nausea and vomiting is not just limited to the morning and it’s not exclusive to the first trimester of pregnancy, contrary to popular belief. It’s unknown exactly what causes it, although some doctors believe it may be a reaction to the pregnancy hormone. For most women, it’s deeply unpleasant but manageable.

For a few, however, it can be devastating or even deadly. Morning sickness can be so violent and severe that a woman might vomit as much as fifty times a day, in a severe complication of pregnancy known as hyperemesis gravidarum. This condition, which affects up to 3 percent of pregnancies, leads to dehydration and starvation, endangering her wellbeing as well as that of the fetus.

Now a new drug that brings relief may be on the horizon. Xoneva, which is finishing clinical trials in the UK, has been found to reduce nausea by two thirds and reduce episodes of vomiting by 75 percent. The hope is that could ultimately improve outcomes for both mothers and babies affected by the disorder. The drug has just been licensed for use in Britain.

“We know that many women are simply told to put up with debilitating symptoms on the basis that no medication is safe in pregnancy, when in fact the risks of not treating may be significantly higher. Our hope is that a licensed product will give doctors confidence to prescribe for women who need it,” said Clare Murphy, Director of External Affairs at British Pregnancy Advisory Service (Bpas).

Hyperemesis-affected women may vomit so frequently and violently that their retinas detach, ribs fracture, eardrums burst, or esophagus ruptures. “The vomiting was also violent. It felt like my head would explode each time, so as I vomited – due to the pressure in my head – my nose would bleed so blood was coming out of my nose and my mouth simultaneously,” said Sheila Nortley, who suffered from the condition. “My career came to a halt. I could not go anywhere because I was either too weak or too afraid I’d vomit all over myself. I became completely dependent on family.”

Other potential side effects include blackouts and brain damage from severe malnutrition. It can also lead to Wernicke’s Encephalopathy (WE), a severe neurological condition caused by a deficiency in thiamin (vitamin B1). Even after the pregnancy is over, the condition casts a long shadow. Women who suffer from hyperemesis have a 3.6-fold increased lifetime risk of emotional disorders, such as depression and anxiety, and 18 percent experienced the full criteria of post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Babies born to women who suffer from hyperemesis can suffer from long-term health consequences as a result of severe nutritional deficiencies, and have a three-fold increased risk of neurodevelopmental delay.

Until the medical community found ways to manage it in the mid-20th century, it was the leading cause of maternal death. In the 1800s, author Charlotte Brontë is believed to have died from the condition. More recently, Kate Middleton, Duchess of Cambridge, brought hyperemesis to the public’s attention when she was hospitalized for the condition during her pregnancies. Treatments includes intravenous feeding and hydration, as well as various medications. In one of every seven cases, a woman is forced to terminate a wanted pregnancy due to the life-threatening severity of the condition.

“Bpas sees women whose sickness is so debilitating they are left with no choice but to terminate what is often a very much wanted pregnancy; with early treatment with medications including Xonvea, our hope would be that for at least some women, their symptoms and sickness will not escalate to the point that they need our services,” said Murphy.

In the 1950s, a drug called thalidomide was used to treat hyperemesis, until it was discovered that the drug led to severe birth defects, including missing or malformed limbs. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, and in Spain until the 1980s, more than 10,000 babies were born with these deformities. Only half of those babies survived. The drug is no longer used on pregnant women. Another drug, Zofran, an antiemetic commonly used to control nausea in chemotherapy patients, is sometimes used today.

“Hyperemesis is a true disease like any other disease,” says Marikim Bunnell, an OB-GYN at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “Zofran is a miracle drug for some people.” However, it too has been blamed for birth defects. The Food and Drug Administration classifies it as a Category B drug, which means it has been tested in animals but not people, and warns that “this drug should be used during pregnancy only if clearly needed.”

Because of the complicated history of these medicines, the arrival of Xonvea is being met with some resistance. Xonvea was actually already used in the US and UK between 1956 and 1983 under the names Debendox and Benedictin. It was withdrawn from use in the 1980s after claims it was linked to birth and development defects. It returned to the U.S. in 2006 after a panel concluded that there was no association between the drug and fetal abnormalities, and now UK researchers also say that it is safe.

@DuncanCecil/X

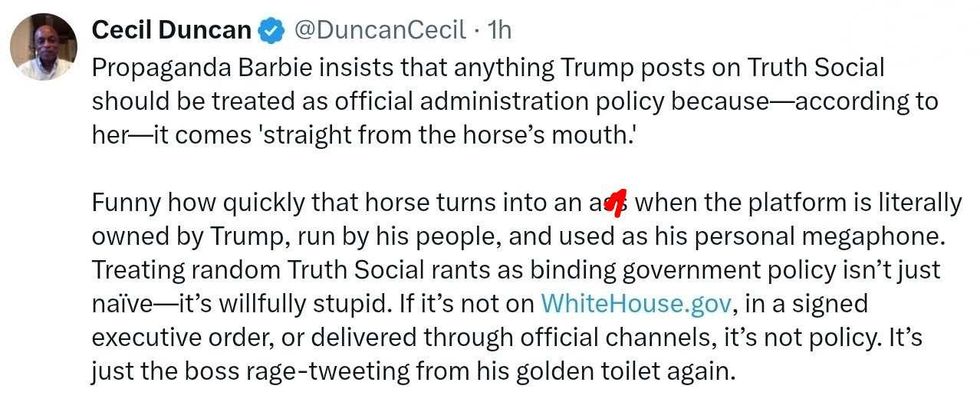

@DuncanCecil/X @@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social

@@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social @89toothdoc/X

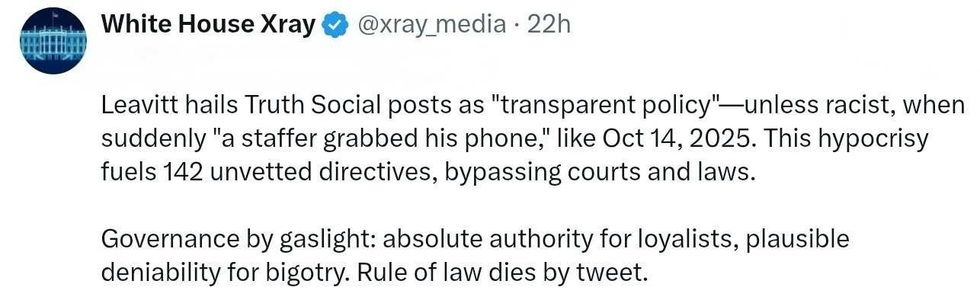

@89toothdoc/X @xray_media/X

@xray_media/X @CHRISTI12512382/X

@CHRISTI12512382/X

@sza/Instagram

@sza/Instagram @laylanelli/Instagram

@laylanelli/Instagram @itssharisma/Instagram

@itssharisma/Instagram @k8ydid99/Instagram

@k8ydid99/Instagram @8thhousepath/Instagram

@8thhousepath/Instagram @solflwers/Instagram

@solflwers/Instagram @msrosemarienyc/Instagram

@msrosemarienyc/Instagram @afropuff1/Instagram

@afropuff1/Instagram @jamelahjaye/Instagram

@jamelahjaye/Instagram @razmatazmazzz/Instagram

@razmatazmazzz/Instagram @sinead_catherine_/Instagram

@sinead_catherine_/Instagram @popscxii/Instagram

@popscxii/Instagram