Scientists say they may have completed yet another piece of the puzzle that could lead to same-sex partners someday being able to bear genetic offspring.

However, it’s only been attempted in mice, and experts say there’s a long way to go before it could even be considered for humans.

While living mice produced by same-sex mouse partners have been born before, the process has only been successful with two females. A Chinese study published in October in the journal Cell Stem Cell reports, though, that for the first time living pups have been produced from two males.

Typically, when placental mammals reproduce, the sperm and the egg work together in what’s called “imprinting,” when parts of the mother's DNA and parts of the father's DNA get different “tags” that affect how they will work in the offspring.

For the experiment, scientists cut out the genes that carried these kinds of imprinting-dependent tags — for females they found they had to cut three, and for males, seven. The research team ultimately made 200 attempts at creating mouse pups with two mothers, and succeeded 27 times.

However, it took 500 attempts to make mouse pups with two fathers, resulting in 12 live births. And, unlike the female mice’s babies, none of the males’ offspring survived to adulthood. In fact, only two lived longer than 48 hours.

Not exactly surprising, given that offspring produced by two males is virtually unheard of in nature, while some fish, frogs and lizards — Komodo dragons, for example — can naturally produce young with two females.

“To make an individual, you have to have an egg; males don't have eggs,” Richard Behringer, a developmental biologist at the University of Texas, told National Geographic.

Edited stem cells can simply be inserted into the egg of another female, but for two males, the process is quite a bit more complicated. To make “bipaternal” offspring, the scientists must inject sperm and the edited stem cells into an immature egg without a nucleus, the component where most genetic material is stored. The egg then has to be matured outside a surrogate mouse before it can be successfully implanted in her uterus.

Even though the female-offspring mice appeared healthy and even were able to bear their own young, the effects of gene editing on their long-term health have yet to be known.

“When you do the gene targeting, you may get some unintended side effects. You may alter other sequences which you didn't mean to alter,” Azim Surani, a developmental biologist at the University of Cambridge, told National Geographic. These changes are then passed down to the next generation, where harmful effects could eventually emerge.

Not only that, but the ethical considerations of genetically altered children, especially considering the as-yet-unclear implications of gene editing in the adult mice, are immense and potentially impassable.

“It is never too much to emphasize the risks, and the importance of safety, before any human experiment is involved,” Wei Li at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, one of the study authors, told New Scientist. “But we think our work does take it closer.”

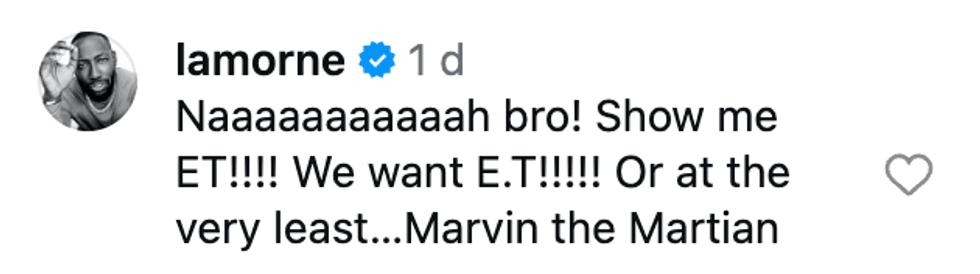

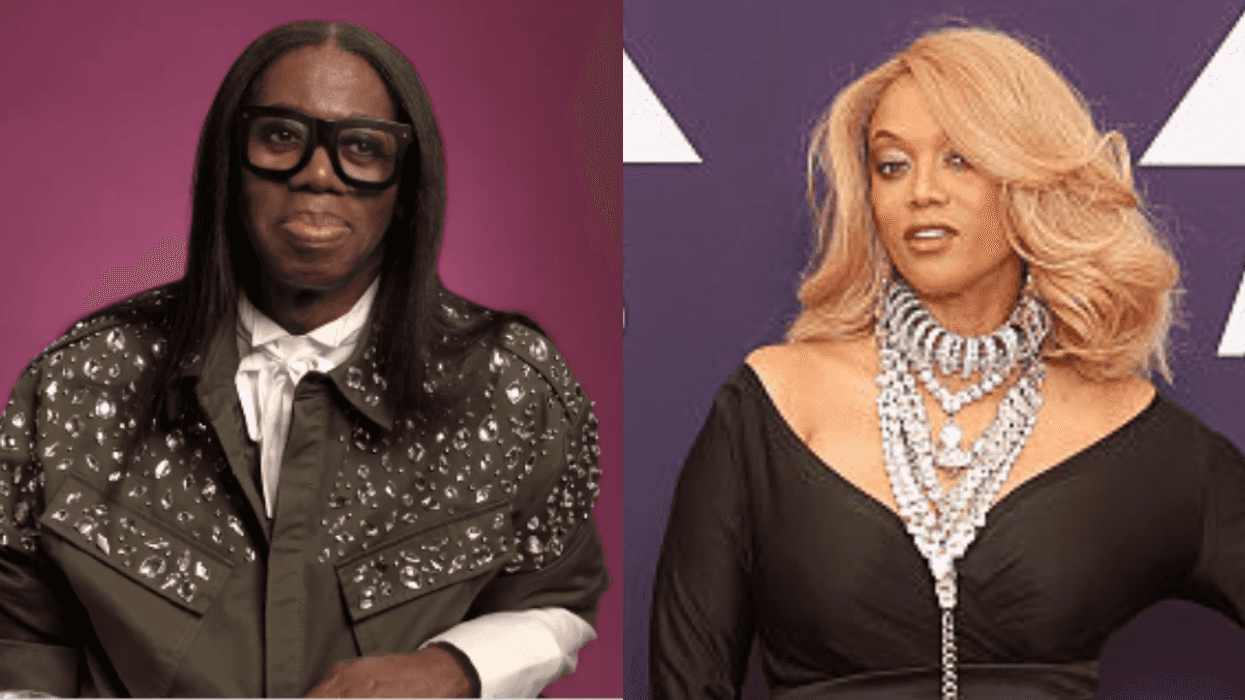

@lamorne/Instagram

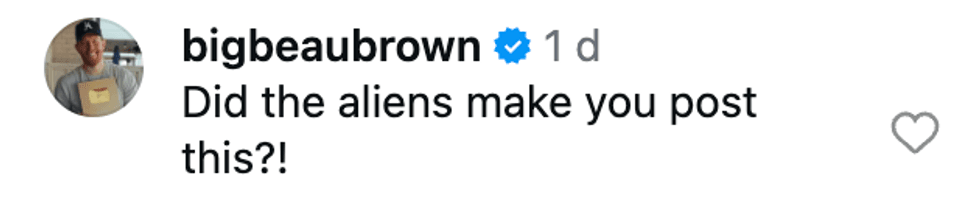

@lamorne/Instagram @bigbeaubrown/Instagram

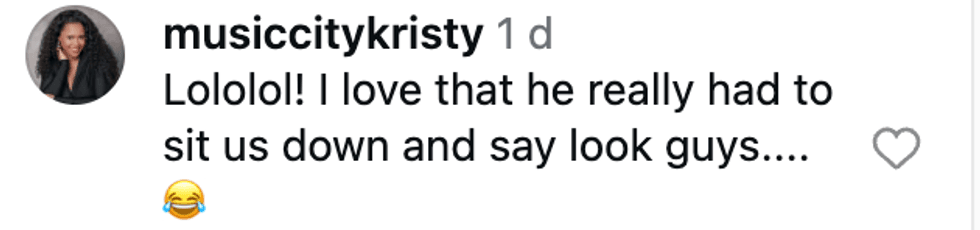

@bigbeaubrown/Instagram @musiccitykristy/Instagram

@musiccitykristy/Instagram @phil_torres/Instagram

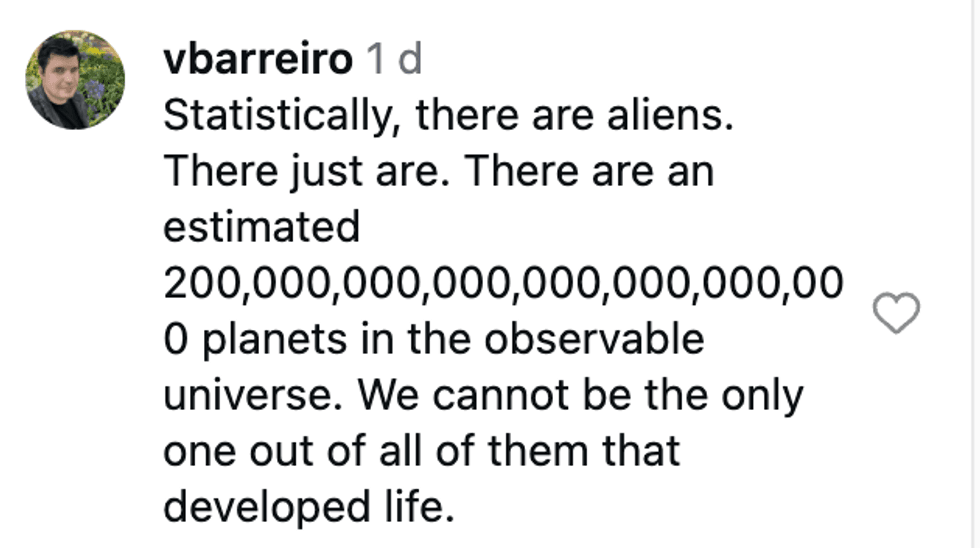

@phil_torres/Instagram @vbarreiro/Instagram

@vbarreiro/Instagram @franklinjleonard/Instagram

@franklinjleonard/Instagram @br1an02/Instagram

@br1an02/Instagram @ohhelloitsmax/Instagram

@ohhelloitsmax/Instagram @frecklesmarie/Instagram

@frecklesmarie/Instagram

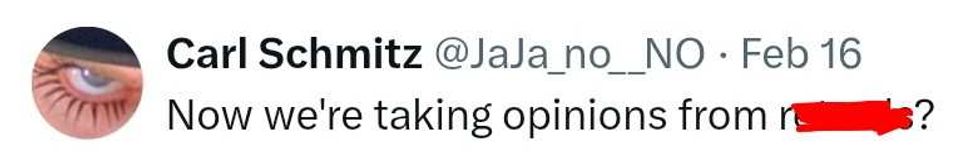

@JaJa_no_NO/X

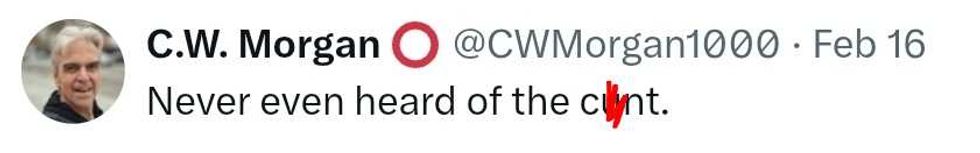

@JaJa_no_NO/X @CWMorgan1000/X

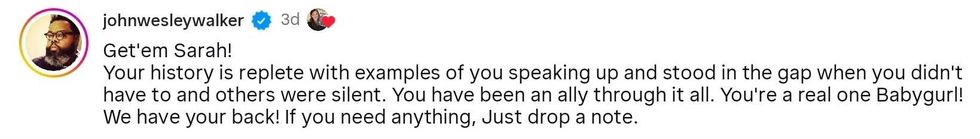

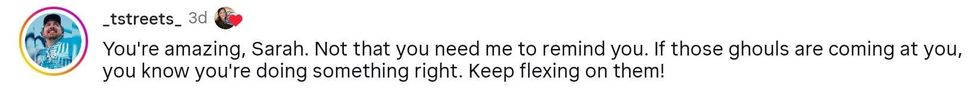

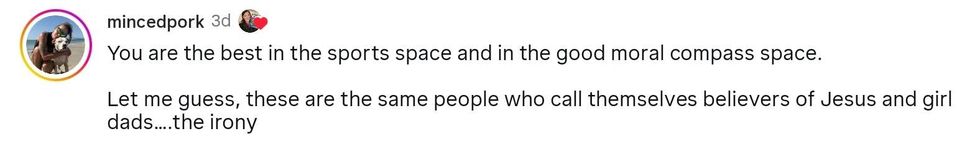

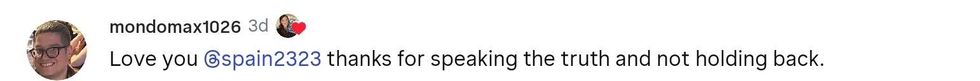

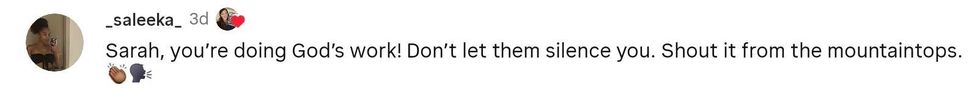

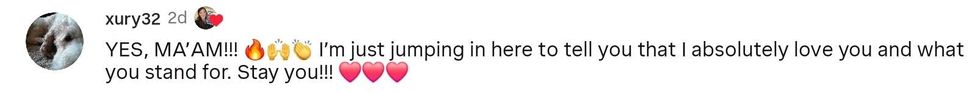

@CWMorgan1000/X reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram