[DIGEST: Washington Post, Jezebel, Hot Air, Death and Taxes]

Prostitution is not the oldest profession, but the “oldest oppression,” writes Jimmy Carter in a controversial editorial for The Washington Post. The former president of the United States said he does not believe consensual work exists and strongly disagreed with assertions that prostitution can be an affirmation of female agency: “[But] I cannot accept a policy prescription that codifies such a pernicious form of violence against women.” He then suggested a change in policy “consistent with advancing human rights and societies,” but certain critics are finding faults with his proposal.

Carter favors “the Nordic model” and refers to his 2014 book, A Call to Action: Women, Religion, Violence and Power, when explaining why he disagrees with human rights organizations such as Amnesty International and UNAIDS on the decriminalization of sex work. The Nordic model, adopted in Sweden, Canada and France, decriminalizes the selling of sex. Managing, pimping and buying of sex, however, remain illegal. “Normalizing the act of buying sex also debases men by assuming that they are entitled to access women’s bodies for sexual gratification,” Carter writes. “If paying for sex is normalized, then every young boy will learn that women and girls are commodities to be bought and sold.”

But critic Anna Merian says the Nordic model is problematic and that Amnesty “stopped supporting the Nordic model after doing something we’re not sure President Carter has ever tried: they talked to sex workers about it.” Merian points to a Q&A entitled “Policy To Protect The Human Rights of Sex Workers,” in which Amnesty notes that the model “provides a better scope for sex workers’ rights to be protected” (these rights include access to health care and the ability to report crimes to the authorities). Regardless, “laws against buying sex and against the organisation of sex work can harm sex workers,” as in the case of sex workers who relayed feeling “pressured” to visit buyers’ homes so they could avoid the police, a position resulting not only in loss of control, but the compromise of their safety. Sex workers are also penalized under the Nordic model for organizing for their safety. Safe accommodations can be hard to come by as well: landlords face potential prosecution for letting premises to sex workers. Forced evictions become the next logical step.

Merian also accuses the former president of moralism, as when she writes that Carter is “doubling down, though, arguing that decriminalization doesn’t just hurt sex workers; it hurts everybody, somehow, by devaluing the sex you’re having and the nature of sex itself.” Indeed, while Carter suggests that sex should ideally be “between people who

experience mutual enjoyment,” in the absence of enjoyment, he stresses, “one party has power over another to demand sexual access, mutuality is extinguished, and the act becomes an expression of domination.” Viewing sex work as demeaning is not an invalid opinion, writes Merian, but “in a world where men and women engage in sex work either by choice, for survival—or, most often, in a complicated mixture—Carter’s pet solution continues to be a dead end.”

Critic Jazz Shaw shares Merian's view, and does not mince words. “The major shortcoming of Carter’s approach, as noble, moral and Biblical as it might sound, is that it doesn’t work very well in the context of our legal system,” Shaw writes. “If the selling of sex is to remain illegal (which it probably shouldn’t) then both the buyer and the seller are at fault. Plenty of poor people have taken up selling drugs out of desperation, addiction or a lack of other options, I’m sure, but we don’t simply lock up the buyers and send the dealers on their way… This approach makes no sense.”

Shaw admits having a libertarian bias, but notes that it’s foolish to assume “that every woman who is out there selling sex is doing it because it was her chosen profession and she likes to sleep in late on weekdays…” While there are women who approach prostitution in this manner, Shaw notes that everyone else can be “broken down into what I’m sure are three overly generalized categories,” which include those who have no other options, those suffering from drug addictions or mental illness and those who may be “actual hostages of pimps and sex traffickers.” In this final regard, Shaw’s view of Carter is more sympathetic, though considerably more radical: While he supports community outreach and the mutual efforts of both law enforcement and governing bodies to rescue women from a potentially dangerous and destructive cycle, he advocates for the public executions of pimps to “disincentivize the practice.”

Carter may believe that regulating prostitution would “abandon the equal dignity of each human being,” but writer Jamie Peck criticizes him for ignoring other voices in the sex trade: “He bases this belief, as so many others have, on the idea that sex work is inherently demeaning to women. (Male and gender non-binary SWs do not seem to exist in his world.)” The Nordic model’s end goal, writes Peck, “is to abolish sex work altogether, depriving people of much needed income. Until the Nordic model is prepared to give people another way they can make many times the minimum wage using only their bodies, it has no business telling them how to make a living.”

“I do not mean to pick on Jimmy Carter,” she continues. “I’m sure he’s a good man with good intentions. But he’s dangerously incorrect on this subject… I agree that it’s exploitative when someone must sell their sexual labor to those with more power than them in order to survive.” She does, however, conclude on a more positive note. “‘Abolishing’ sex work within the wage system is a big middle finger in the face of anyone who doesn’t provide for themselves in the way those in power see fit. That said, I welcome Carter as an ally in the fight against global capitalism, should he someday follow his opinion to its logical conclusion.”

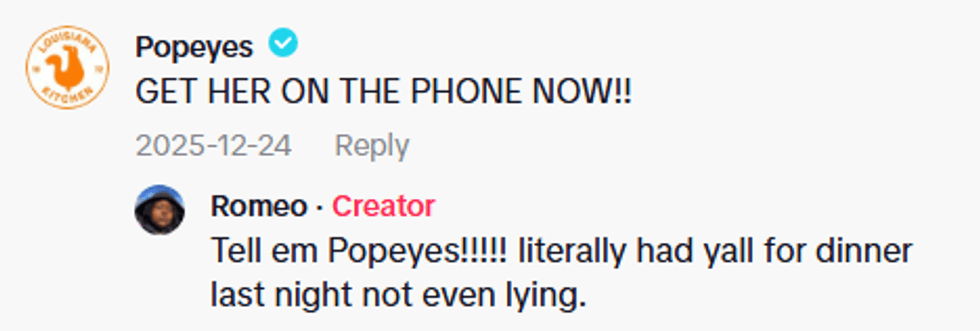

@romeosshow/TikTok

@romeosshow/TikTok @romeosshow/TikTok

@romeosshow/TikTok @romeosshow/TikTok

@romeosshow/TikTok @romeosshow/TikTok

@romeosshow/TikTok @romeosshow/TikTok

@romeosshow/TikTok @romeosshow/TikTok

@romeosshow/TikTok @romeosshow/TikTok

@romeosshow/TikTok @romeosshow/TikTok

@romeosshow/TikTok @romeosshow/TikTok

@romeosshow/TikTok @romeosshow/TikTok

@romeosshow/TikTok

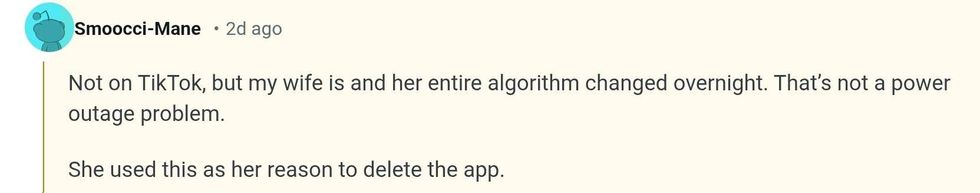

r/technology/Reddit

r/technology/Reddit r/technology/Reddit

r/technology/Reddit r/technology/Reddit

r/technology/Reddit r/technology/Reddit

r/technology/Reddit r/technology/Reddit

r/technology/Reddit r/technology/Reddit

r/technology/Reddit r/technology/Reddit

r/technology/Reddit r/technology/Reddit

r/technology/Reddit r/technology/Reddit

r/technology/Reddit r/technology/Reddit

r/technology/Reddit r/technology/Reddit

r/technology/Reddit r/technology/Reddit

r/technology/Reddit r/technology/Reddit

r/technology/Reddit r/technology/Reddit

r/technology/Reddit r/technology/Reddit

r/technology/Reddit