Writing for Bloomberg, Timothy L. O'Brien, the author of TrumpNation: The Art of Being The Donald, takes President Donald Trump to task for "running a very long con on the American public," adding that questioning the president's tactics "raises a question that now has an urgency it didn't decades ago: How long can the long con last?"

"Trump's shtick in its early days was limited to New York, and most New Yorkers (who, of course, have good antennae for such things) knew it was awash in snake oil," O'Brien observes. He notes further:

Yes, Trump might say he was a business titan worthy of the Forbes 400. But he wasn't among the upper echelon of New York real-estate developers, he wasn't a fixture of civic life, and he seemed more at home on Page Six than on the front page of the Wall Street Journal.

Trump's love of the con -- borrowing billions he couldn't repay so he could invest in splashy properties and projects he didn't understand -- drew national attention and blanket media coverage just before the game unraveled in serial bankruptcies in the early 1990s. After that debacle, Trump refashioned himself as a ubiquitous media curiosity, one who held center stage in part by being the one famous guy who could reliably be called upon to chat about sex, women and even his own genitals.

It was Trump's "emergence" on The Apprentice in 2004, O'Brien observes, which, he says, "enabled him to extend the con once again":

He had been spinning myths about being a can-do businessman for years, but the show allowed him to play an entrepreneurial guru in front of millions of people each week. Although it soon fizzled, Trump used the show to refashion himself as a calculating executive -- one who some thought might just be talented enough to shake up the federal government.

O'Brien recalls that Trump later sued him for libel after the publication of TrumpNation, "because, among other things, the book scrutinized his years of patty-cake with Forbes to get on its rich-list while also raising doubts about whether he was a billionaire."

According to former Forbes journalist Jonathan Greenberg, in 1984, Trump posed as "John Barron," a Trump Organization official who attempted to convince Greenberg of "how loaded Donald J. Trump really was." ("Barron" claimed Trump was worth five times the $200 million he was evaluated to be worth at the time.)

As Greenberg notes:

At the time, I suspected that some of this was untrue. I ran Trump's assertions to the ground, and for many years I was proud of the fact that Forbes had called him on his distortions and based his net worth on what I thought was solid research.

O'Brien himself notes that Trump lost the case against Forbes in 2011:

During a deposition, Trump conceded that he was so broke at one point that he had to borrow millions of dollars from his father's estate to avoid personal bankruptcy -- something he had earlier contested when I asked him about it during our many conversations for the book. ("I had zero borrowings from the estate," Trump told me. "I give you my word.")

Greenberg mentioned my reporting as one reason why he came to realize that Trump had hoodwinked him over the years, and cited documents that were available to me but not to him when he was at Forbes.

And there are "plenty of reasons" to doubt Trump's relationship to the truth:

Between 1982 and 1983, for example, the magazine allowed the Trump family's stated real-estate fortune to double from $200 million to $400 million, even though a savage recession was underway. In 1989, Forbes ranked Trump 26th on its list, then dropped him entirely a year later. He was gone for five years and then resurfaced with $450 million in 1996. That jumped to $1.4 billion a year later. And so on.

You don't need tape recordings to understand this con. You just need common sense.

But Trump's obsession with Forbes and maintaining an image of having unadulterated wealth at his disposal never waned.

"It seems to be that they're the barometer of individual wealth. It doesn't really matter. It matters much less to me today than it did in the past," he told O'Brien in 2005 when asked about his need to be perceived as a billionaire.

"That was false, of course" O'Brien writes, noting that a decade later, the future president "would brag about being worth more than $10 billion" while on the campaign trail.

Trump has latched onto such fanciful figures not simply because he's insecure about his wealth, but because he knows that pretending he has that kind of money keeps him in the media's eye and keeps potential business partners interested in him. It's all part of the long con.

"That con now has global consequences," O'Brien observes:

Trump doesn't fulminate about North Korea or building a wall on the Mexican border because he's a policy maven with deeply held principles. It's because he knows that toying around with sensitive and sometimes dangerous subjects gets the media's attention and keeps certain blocs of voters interested in him.

That's part of the long con too. And the president will keep it up -- and get away with it -- as long as voters play along.

Trump's hypocrisy is well documented, and a particularly potent example of the con came to light shortly after he galvanized his base with claims that he would have run into Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School––where gunman Nicolas Cruz murdered 17 people on Valentine's Day––even if he was not armed.

On the heels of this controversy came the release of a recently unearthed interview Trump gave on The Howard Stern Show on July 16, 2008. Trump often held court on the shock jock's program, and during this particular appearance, he discussed his distaste for blood.

"I'm not good for medical. In other words, if you cut your finger and there's blood pouring out, I'm gone," he told Howard Stern at the time.

Trump then tells Stern about the time he believed a man died in front of him during a charity event at Mar-a-Lago, his private club. Trump "turned away in disgust at the sight of his blood," rather than help the injured man.

He says:

I was at Mar-a-Lago and we had this incredible ball, the Red Cross Ball, in Palm Beach, Florida. And we had the Marines. And the Marines were there, and it was terrible because all these rich people, they're there to support the Marines, but they're really there to get their picture in the Palm Beach Post… so you have all these really rich people, and a man, about 80 years old—very wealthy man, a lot of people didn't like him—he fell off the stage… So what happens is, this guy falls off right on his face, hits his head, and I thought he died. And you know what I did? I said, 'Oh my God, that's disgusting,' and I turned away," said Trump. "I couldn't, you know, he was right in front of me and I turned away. I didn't want to touch him… he's bleeding all over the place, I felt terrible. You know, beautiful marble floor, didn't look like it. It changed color. Became very red. And you have this poor guy, 80 years old, laying on the floor unconscious, and all the rich people are turning away. 'Oh my God! This is terrible! This is disgusting!' and you know, they're turning away. Nobody wants to help the guy. His wife is screaming—she's sitting right next to him, and she's screaming… What happens is, these 10 Marines from the back of the room… they come running forward, they grab him, they put the blood all over the place—it's all over their uniforms—they're taking it, they're swiping [it], they ran him out, they created a stretcher. They call it a human stretcher, where they put their arms out with, like, five guys on each side… I was saying, 'Get that blood cleaned up! It's disgusting!' The next day, I forgot to call [the man] to say he's OK. It's just not my thing.

You can listen to the recording HERE.

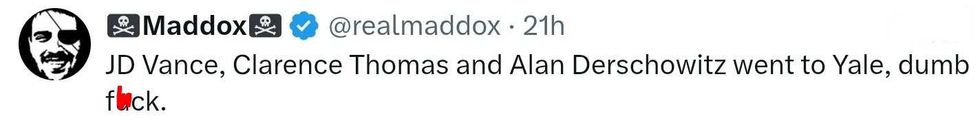

replying to @elonmusk/X

replying to @elonmusk/X replying to @elonmusk/X

replying to @elonmusk/X replying to @elonmusk/X

replying to @elonmusk/X replying to @elonmusk/X

replying to @elonmusk/X

Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook Barry Manilow/Facebook

Barry Manilow/Facebook