Samsung has decided it will discontinue its Galaxy Note 7 smartphone after dozens of reports of devices exploding and catching fire. The Korean firm was forced to recall 2.5 million phones after they went on sale in August, but agreed to halt production permanently following reports that replacement phones were also exploding.

“Because consumers’ safety remains our top priority, Samsung will ask all carrier and retail partners globally to stop sales and exchanges of the Galaxy Note 7 while the investigation is taking place,” the company said in a statement. “Consumers with either an original Galaxy Note 7 or replacement Galaxy Note 7 device should power down and stop using the device and take advantage of the remedies available.” Samsung shares tumbled 8 percent in Seoul as a result. Apple shares rose 1.7 percent after Samsung halted production.

Initially, critics hailed the premium device––which sold for at least $850 in the United States––as the best Android on the market. Customer excitement waned as safety concerns increased, however. A number of customers began to report their phones were exploding, including one in a car and another aboard a passenger jet. Samsung customers criticized the company for its response to these reports. Many customers expressed confusion over whether their phone was safe to use, whether they should return them and whether the company would offer replacement devices.

Samsung told its South Korean customers on Tuesday that they can exchange their Note 7 for another smartphone. The exchange program will begin tomorrow and run through the end of the year. Samsung has not outlined its plans to compensate customers in other markets. Discontinuing the Note 7 could cost Samsung roughly $9.5 billion in lost sales and $5.1 billion of profit.

According to science reporter Sean Hollister, the science behind why these phones exploded is relatively straightforward. Phones “use lithium ion battery packs for their power, and it just so happens that the liquid swimming around inside most lithium ion batteries is highly flammable,” he wrote. “If the battery short-circuits––say, by puncturing the incredibly thin sheet of plastic separating the positive and negative sides of the battery––the puncture point becomes the path of least resistance for electricity to flow.” It then, he continued, “heats up the battery’s flammable liquid electrolyte at that spot.” Should the liquid heat up quickly enough, the battery can explode.

But the Galaxy Note 7 is not the first phone to catch fire, Hollister noted. Nor is it the first phone to face a “giant” recall. Cell phone battery explosions prompted an investigation by the United States Consumer Product and Safety Commission in 2004. And in 2009, Nokia had to recall 46 million phone batteries that were at risk of short-circuiting. “We've known for years that lithium ion batteries pose a risk, but the electronics industry continues to use the flammable formula because the batteries are so much smaller and lighter than less-destructive chemistries,” he concluded. “Lithium-ion batteries pack a punch, for better or for worse.”

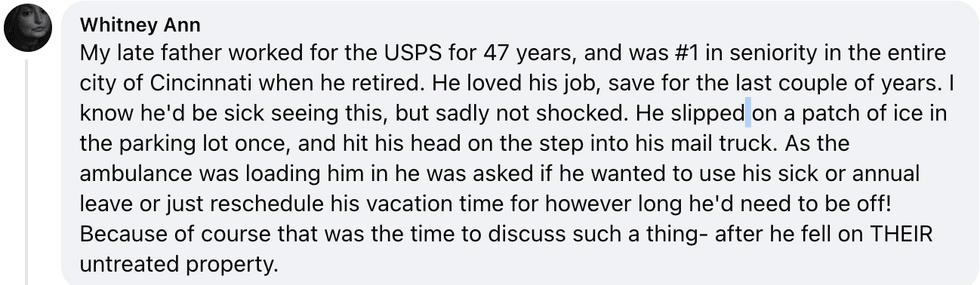

Whitney Ann/Facebook

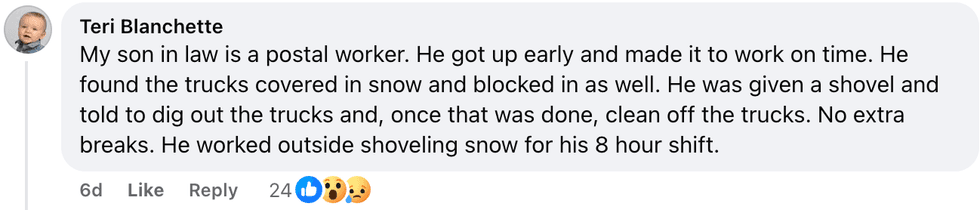

Whitney Ann/Facebook Teri Blanchette/Facebook

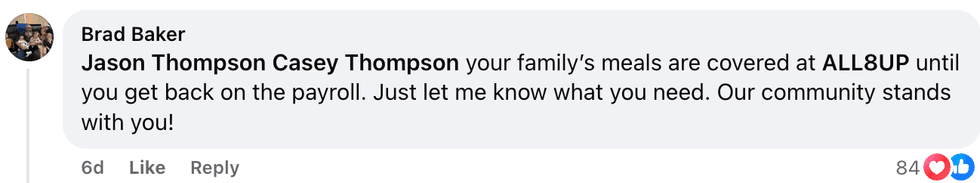

Teri Blanchette/Facebook Brad Baker/Facebook

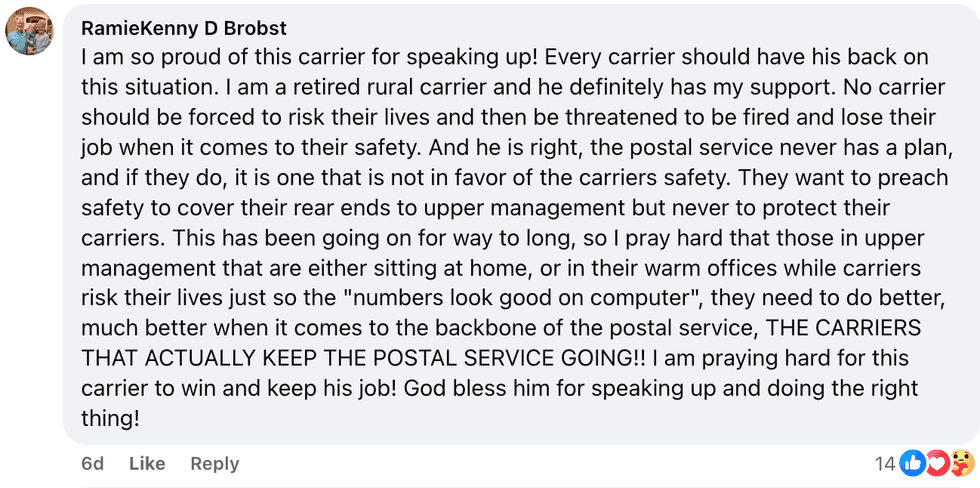

Brad Baker/Facebook RamieKenny D Brobst/Facebook

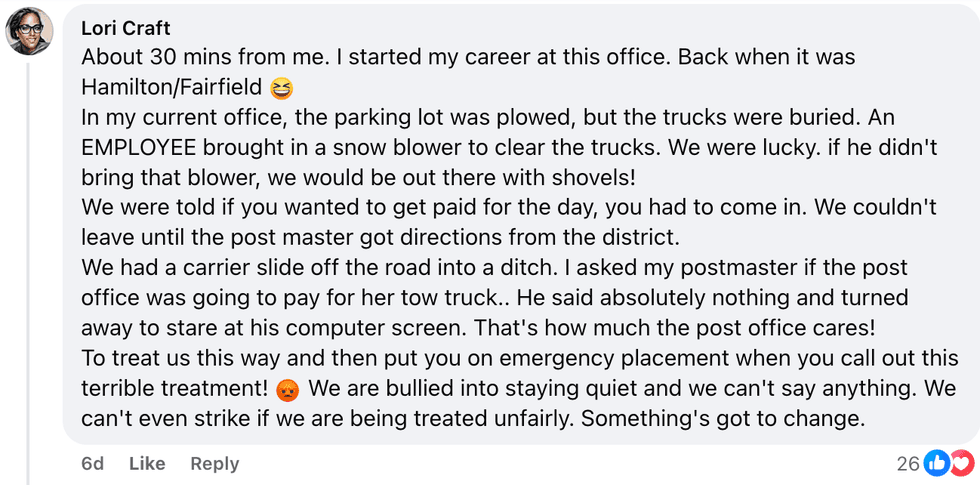

RamieKenny D Brobst/Facebook Lori Craft/Facebook

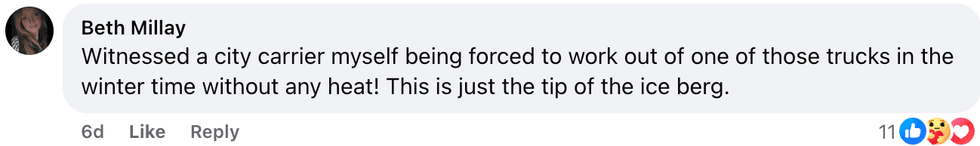

Lori Craft/Facebook Beth Millay/Facebook

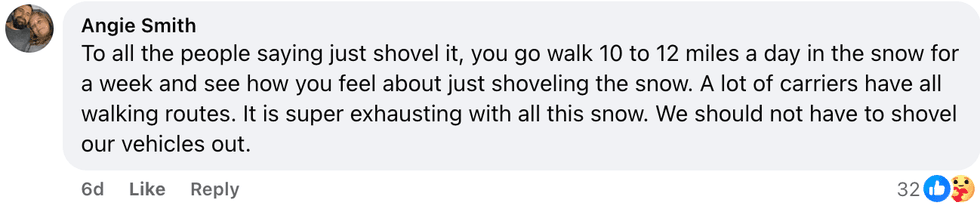

Beth Millay/Facebook Angie Smith/Facebook

Angie Smith/Facebook Ann Bechtold Larkin/Facebook

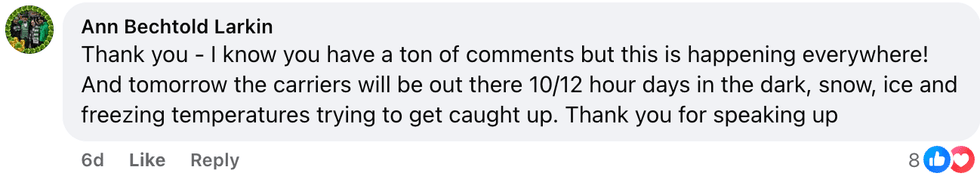

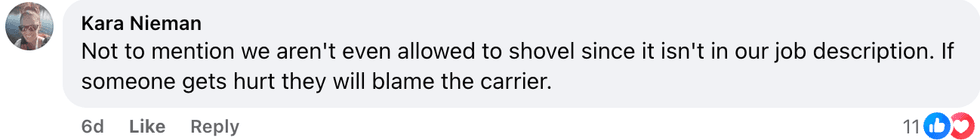

Ann Bechtold Larkin/Facebook Kara Nieman/Facebook

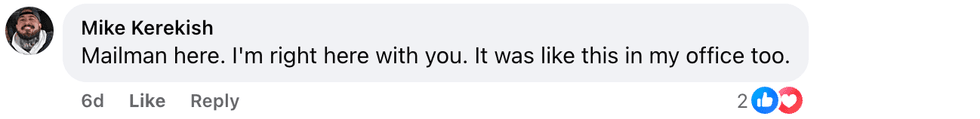

Kara Nieman/Facebook Mike Kerekish/Facebook

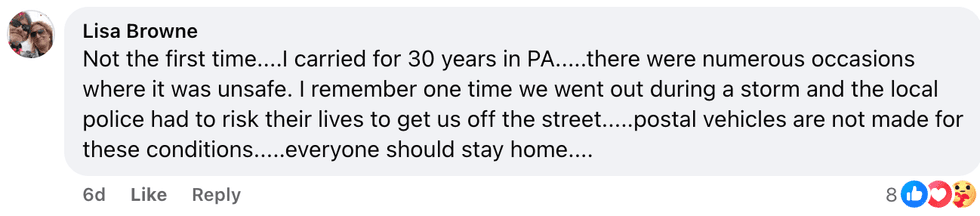

Mike Kerekish/Facebook Lisa Browne/Facebook

Lisa Browne/Facebook Ashley Crenshaw/Facebook

Ashley Crenshaw/Facebook

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

ourpinkwitchh/Instagram

@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social

@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social

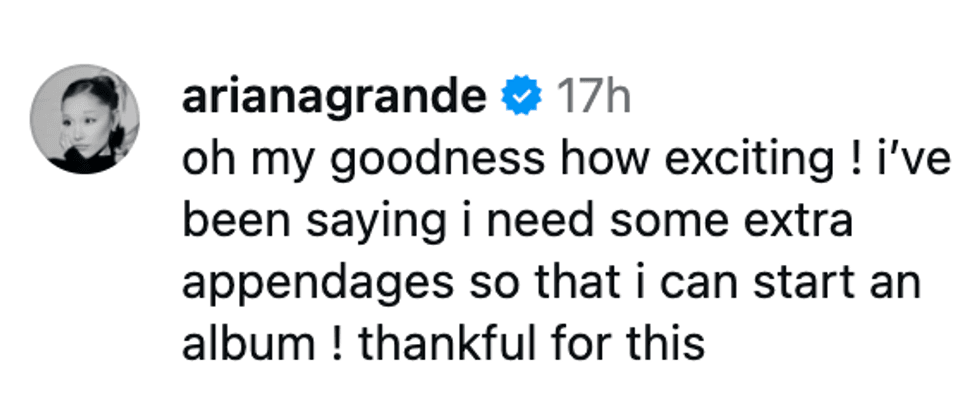

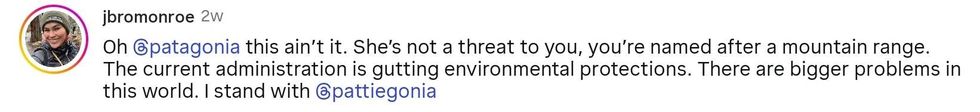

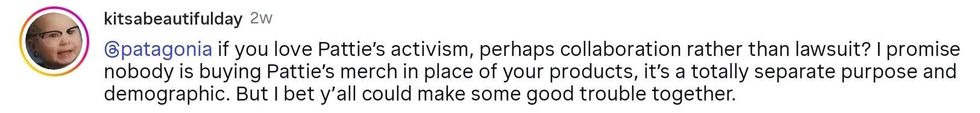

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

reply to @pattiegonia/Instagram

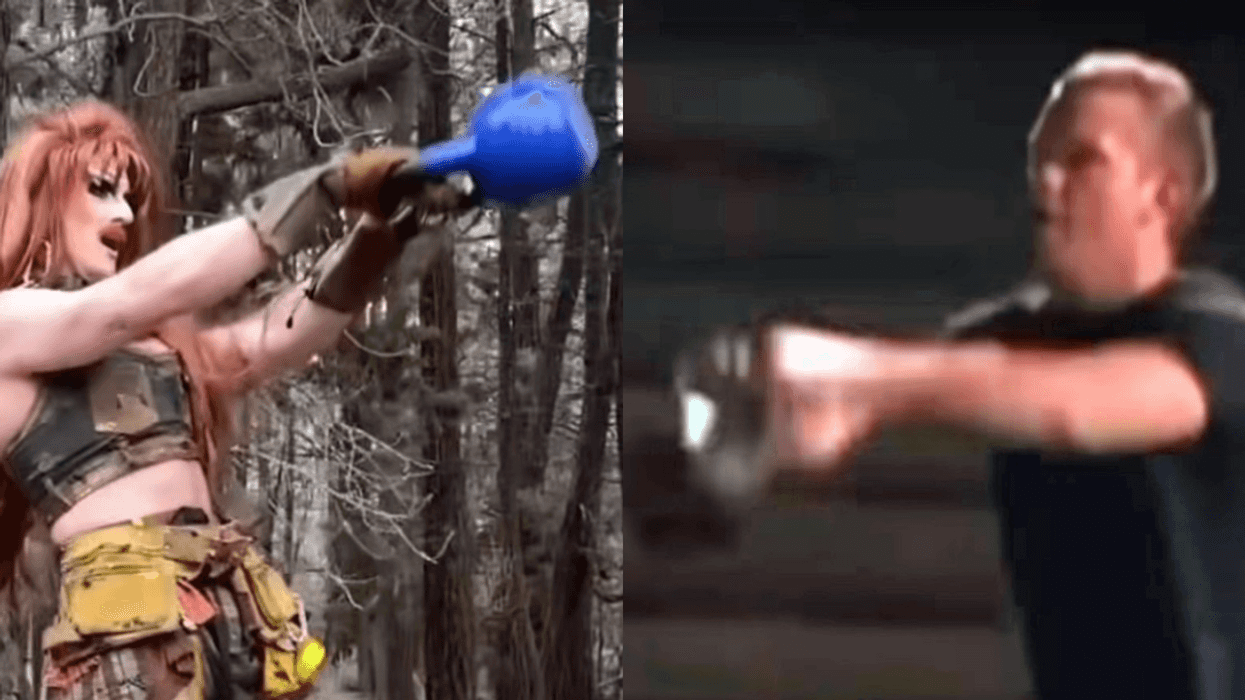

reply to @joeknowsventura/Instagram

reply to @joeknowsventura/Instagram reply to @joeknowsventura/Instagram

reply to @joeknowsventura/Instagram reply to @joeknowsventura/Instagram

reply to @joeknowsventura/Instagram reply to @joeknowsventura/Instagram

reply to @joeknowsventura/Instagram