Fatigue can be a side effect of many other diseases, but with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), it is typically the primary symptom of this potentially debilitating condition that continues to baffle doctors and patients alike.

Like many diseases that tend to affect women in greater numbers than men, CFS, now more formally known as Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) or systemic exertion intolerance disease (SEID), began its introduction into medicine with much skepticism. Its lack of an easily identifiable underlying cause has created a lot of controversy among the scientific community as to whether it is even a real disease.

Now, a new study, published in PLOS ONE, by researchers at Newcastle University in the UK, takes another step forward in the physiological disease model, finding evidence of bioenergetic differences in the immune cells of ME/CFS sufferers as compared to healthy controls.

Physicians began identifying cases of the syndrome in larger numbers in the late 1980s (though there are reports of it in the UK from the 1960s) that mimicked active Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)—the virus that causes mononucleosis—which typically affects teens. Eventually researchers determined that the high EBV virus levels they found in ME/CFS patients were also found in healthy patients, since the virus can lie dormant for years, and most people have been exposed to it. They determined that the cluster of symptoms that defined ME/CFS suggested it was its own animal, though it continues to defy easy classification.

ME/CFS causes extreme fatigue that lasts a minimum of six months and is not improved by sleep or rest, and can include “post-exertional malaise, memory and concentration problems, lymph node sensitivity, and muscle and joint pain,” according to a study in PLOS ONE. Nearly thirty years since the condition began to gain attention, scientists still have no definitive cause and have not yet devised a cure.

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), however, anywhere from 836,000 to 2.5 million Americans suffer from ME/CFS, but most of them have not received a formal diagnosis. In fact, the illness is diagnosed by exclusion, ruling out other disorders and illness that have similar symptoms (such as autoimmune diseases, Lyme disease and even Type 2 Diabetes), since there is not yet an identifiable biomarker of the disease that can be found on any test.

Some badly designed studies have also furthered the ongoing stigma that the illness is not physiological, but psychological— and contributed to unhelpful advice (such as exercise and therapy that can make symptoms worse). Those who have suffered for years are often told by their physicians that they should seek psychological counseling for their physical symptoms. It was even derogatively referred to as “the Yuppie flu” for a time.

However, Australian researchers were the first to bust the myth that ME/CFS was not a real disease when they discovered that the disorder is connected to a faulty cell receptor in immune cells.

One of the Newcastle researchers, PhD student Cara Tomas, has seen how quick physicians are to brush off the disorder and is hopeful that this research can validate this illness for others, and make strides toward treatment.

"A lot of people dismiss it as a psychological disease, which is a big frustration," Tomas told Andy Coghlan at New Scientist.

Kayleigh Bell, a writer who suffers with the disorder, described living with it in a piece for the Huffington Post as, “… my body [is] like a dodgy phone battery. It drains a lot faster than everyone else’s, and even if I charge it multiple times a day it still ends up flat. No amount of sleep feels refreshing and on bad days I ache all over. I feel dizzy and light headed, and struggle to even focus on watching TV. As a bookworm and freelance writer one of the most devastating effects on my life has been my inability to concentrate. My short-term memory is worse than your Nan’s after a few brandies. It’s a battle to pick even a commonplace word out of the alphabet spaghetti soup inside my brain.”

The most recent theories on ME/CFS have suggested that mitochondrial dysfunction of immune cells may drive the severe fatigue, since another syndrome known as “acquired mitochondrial dysfunction” which often occurs after a viral infection can cause similar symptoms. Mitochondria are the energy powerhouses of cells, which produce vital ATP (adenosine triphosphate) that every cell needs in order to function properly. The researchers designed their study to see whether mitochondrial function was abnormal in cells known as peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), which can be easily acquired in simple blood draws.

The Newcastle researchers looked at the two main ways that cells break down their fuel to transfer energy during respiration, called oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis. Changes in these processes could reveal a mitochondrial basis for ME/CFS as well as open up disease pathways to study that would help them identify targets for future study.

The researchers stress tested white blood cells they extracted from 52 patients with ME/CFS and 35 control subjects. These tests looked at the cells’ ability to handle low oxygen levels (such as during exercise, illness or stress).

They found several key differences in these cells’ metabolic processes, most notably the contrast in “maximum levels of respiration.”

When researchers forced the cells to increase energy production, those with CFS could only muster about 50 percent more from their cells. In contrast, the control cells essentially doubled their energy output.

"The CFS cells couldn't produce as much energy as the control cells," Tomas said in a press release.

"At baseline, they didn't perform as well, but the maximum they could reach under any conditions was so much lower than the controls."

The metabolic differences “highlight the inability of CFS patient PBMCs to fulfill cellular energetic demands both under basal conditions and when mitochondria are stressed during periods of high metabolic demand,” the authors write.

Though the study only looked at one immune cell type, Science Alert reported that it is an “important step towards establishing a link between the symptoms of muscle pain, lethargy, and impeded cognitive functions and a biochemical process.”

The researchers are excited about the results of their work but admit that these results “do not establish whether differences in PBMC energy pathways are a cause or a consequence of CFS, however this data clearly implies that these cells may play a role in the disease pathway.”

More research also needs to tackle the controversy over whether CFS and ME are actually two separate disorders, since for some people the more common fatigue symptoms of CFS can have a long slow onset, and the joint aches and swelling that led to the application of the ME term can appear to have sudden onset. More study will be required to confirm this, though a 2013 study in BMJ Open did find that there are different levels of severity of the illness, and patients may benefit from standard measures to classify them according to how ill they are.

In the interim, multiple other theories abound based on small studies. Those that are most likely (but are still being studied), according to the CDC, include:

Infections: since many people describe the onset of their ME/CFS as being flu-like symptoms, researchers suspect there may be small, localized infections (similar to Lyme disease) that are causing the fatigue and pain, even potentially on the Vagus nerve, which is the communication center of the nervous system.

High cytokine levels: ME/CFS is often compared to autoimmune diseases, where the body attacks its own tissues as if they were foreign invaders. However, while studies do show higher levels of cytokines—markers of inflammation in the blood—in ME/CFS patients than in healthy controls, they are not comparable to the levels found in autoimmune illness. However, chronic production of these molecules even in only mildly high amounts could be causing symptoms.

Lower numbers of natural killer cells: The immune system relies upon “natural killer cells” to fight infections. Studies have shown that the NK cells of patients with ME/CFS have NK cells appear to have a lower ability to fight infections, and the less robust the function of NK cells in ME/CFS patients, the more severe their symptoms appear to be.

Differences in T-cell activation: Another theory is that the immune cells known as T-cells, which are integral to the body’s ability to mount an immune response to infection, are not working properly. Some patients with ME/CFS show dysfunctional T-cell activation, but not all.

The Newcastle research is the first to suggest that the answer may lie in energy production at the cellular level.

For people like Kayleigh Bell, the Newcastle research provides not only validation but hope. “I’m positive about the future because the alternative is unthinkable. I have to believe that I’m going to get better and this is illness is just a hiatus from my twenties. In the meantime what would really make my life, and the life of others with ME, a lot easier would be greater public awareness of the illness,” she writes.

@vanessa_p_44/TikTok

@vanessa_p_44/TikTok @vanessa_p_44/TikTok

@vanessa_p_44/TikTok @vanessa_p_44/TikTok

@vanessa_p_44/TikTok @vanessa_p_44/TikTok

@vanessa_p_44/TikTok @vanessa_p_44/TikTok

@vanessa_p_44/TikTok

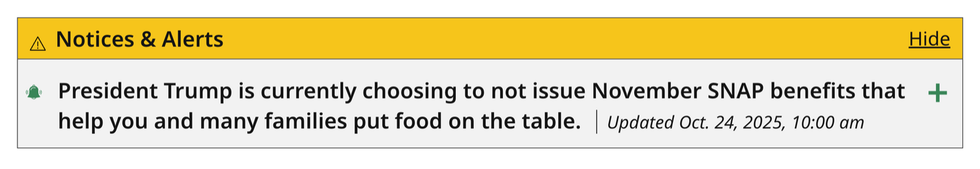

@GovPressOffice/X

@GovPressOffice/X @GovPressOffice/X

@GovPressOffice/X @GovPressOffice/X

@GovPressOffice/X @GovPressOffice/X

@GovPressOffice/X

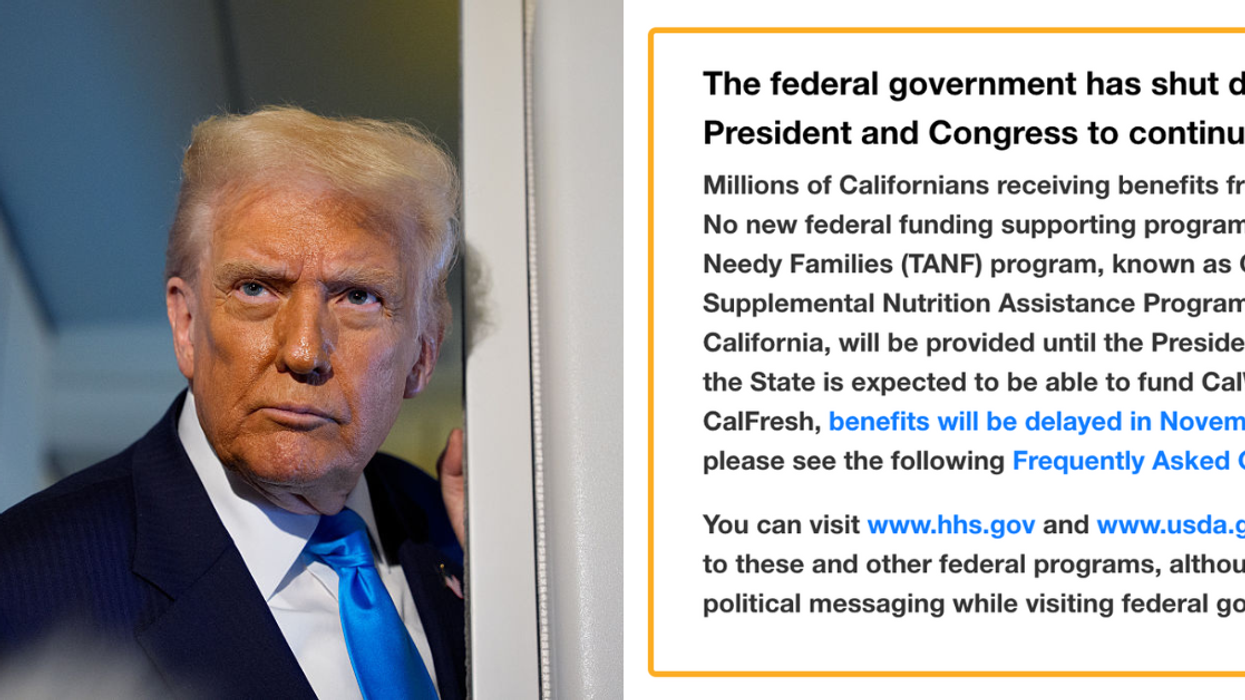

mass.gov

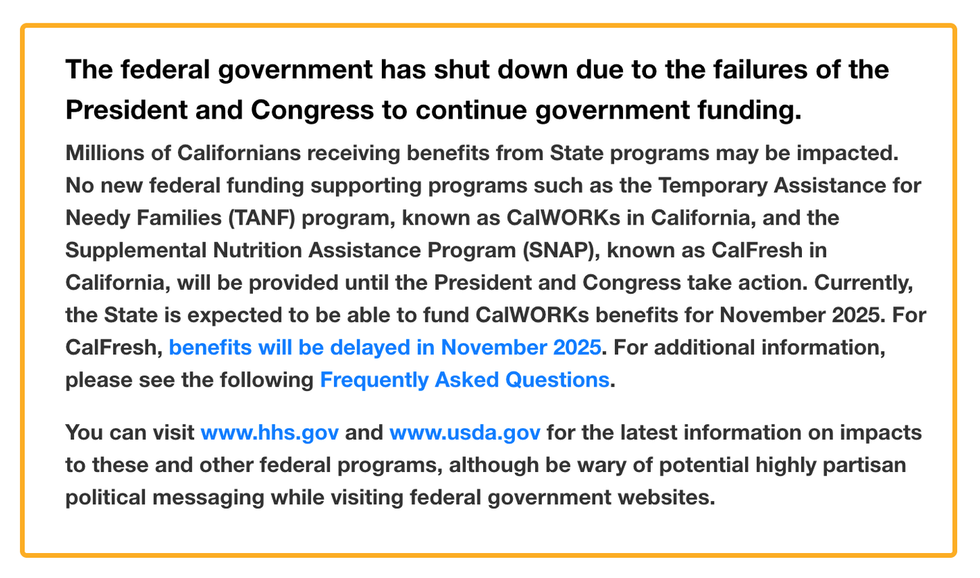

mass.gov cdss.ca.gov

cdss.ca.gov