Animal poachers have long taken advantage of the superiority of the human brain — an advantage that hunters hold over their unsuspecting prey. Humans have caused the extinction of countless species in the animal kingdom including the Pyrenean Ibex, the Passenger Pigeon, Caribbean Monk Seal, Sea Mink, Tasmanian and Javan Tiger.

While dozens more of the world’s creatures are currently at risk of extinction, none share human DNA more than chimpanzees and gorillas. It is perhaps because of this overwhelmingly similar genetic code that young gorillas have figured out how to dismantle noose-like traps to which their peers have fallen victim.

In a calculated act of self-preservation, gorillas inhabiting Rwanda National Park have devised their own solution for foiling the efforts of poachers and hunters. Juvenile gorillas between the ages of two and four have collaborated with each other in an astonishing strategy to survive as a species.

The traps, which are used by hunters to trap food, are not meant for gorilla capture, and the older gorillas can generally extricate themselves when ensnared. The young gorillas, on the other hand, are too small to escape on their own.

The traps work by tying a noose to a branch of bamboo stalk, and bending it down to the ground, with another stick or rock used to hold the noose in place. Dry leaves and branches obscure the whole thing.

When an animal comes along and unknowingly moves the anchoring rock or stick, the branch flings back up and tightens the noose around the animal, holding it in place till the poachers come looking. "If the creature is light enough, it will actually be hoisted into the air," Ker Than wrote for National Geographic.

A research team in Rwanda recently observed groups of young gorillas seeking out and dismantling the camouflaged death traps of their fellow young, critically endangered species, Gorilla beringei beringei.

The research team, while studying endangered primate behavior in Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park, observed a group of primates first search for the traps, then strategically divide in their mission to destroy these mechanisms of death. One gorilla bent and broke the tree while its partner dismantled the noose. The gorilla team then moved on to find another trap and repeated the procedure.

Researchers believe that these gorilla youth had witnessed the deaths of other young primates and made the correlation between the traps and deaths of their peers. Gorilla young stick closely to the leader of the troop, who is usually their father. The father gorilla (called the silverback) uses his canines as tools to rescue a youngster from a hunter’s trap. It is his job to intervene when the younger members are under attack by older members of the troop.

Gorillas are not the only members of the animal kingdom that have learned to work together in teams. For example, emperor penguins must rely on each other to survive the harsh and frigid temperatures of Antarctica. On very cold days, the penguins cluster closely together to help conserve their body heat. These huddles also greatly reduce the amount of food the penguins need to survive.

Chimpanzees, with whom humans share almost 99% of our DNA, are actually closer genetically to humans than they are to other members of the ape family. Like us they have 32 teeth, their body temperature is 98.6 degrees, and their thumbs and big toes are opposable. Their blood type is either A or O. Chimps have been able to learn American Sign Language and, like humans, use facial expressions to communicate their emotions. Other than humans, chimpanzees are the most prolific tool inventors in the animal kingdom.

"The big picture is that we're perhaps 98 percent identical in our sequences to gorillas. So that means most of our genes are very similar, or even identical to, the gorilla version of the same gene," said Chris Tyler-Smith, a geneticist at the Sanger Institute in the UK.

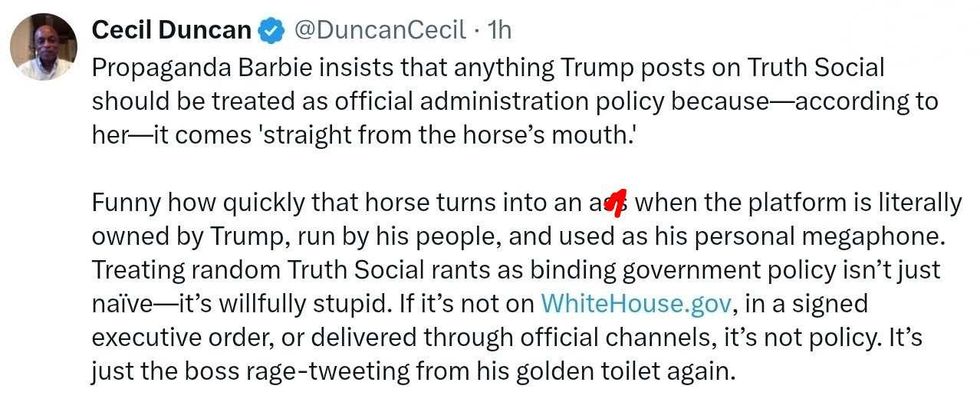

@DuncanCecil/X

@DuncanCecil/X @@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social

@@realDonaldTrump/Truth Social @89toothdoc/X

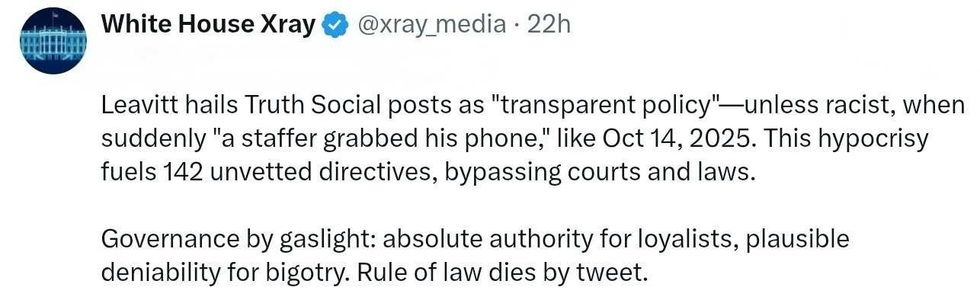

@89toothdoc/X @xray_media/X

@xray_media/X @CHRISTI12512382/X

@CHRISTI12512382/X

@sza/Instagram

@sza/Instagram @laylanelli/Instagram

@laylanelli/Instagram @itssharisma/Instagram

@itssharisma/Instagram @k8ydid99/Instagram

@k8ydid99/Instagram @8thhousepath/Instagram

@8thhousepath/Instagram @solflwers/Instagram

@solflwers/Instagram @msrosemarienyc/Instagram

@msrosemarienyc/Instagram @afropuff1/Instagram

@afropuff1/Instagram @jamelahjaye/Instagram

@jamelahjaye/Instagram @razmatazmazzz/Instagram

@razmatazmazzz/Instagram @sinead_catherine_/Instagram

@sinead_catherine_/Instagram @popscxii/Instagram

@popscxii/Instagram