Fake news and the weaponizing of social media is having profound impacts on world diplomacy and threatens to continue to undermine democracy.

In a report issued on Monday morning, NBC News spoke to experts who have studied the delicate relationship between social media and politics. The impacts of social media on democratic movements can be traced back to the Arab Spring of 2011 when grassroots activists coordinated pro-democracy protests in repressive Middle Eastern countries. But the overwhelming amount of fake news that spread throughout networks during the 2016 U.S. presidential election has many experts concerned over how, and if, the public can discern what is and isn't true.

Experts like Jan Melissen, a professor of diplomacy at the University of Antwerp and a senior research fellow at the Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael, believe that "digital diplomacy" is rapidly eroding the public trust in official information. "There is a now a sense that public diplomacy has become weaponized," Melissen said. "These technologies are being used in ways that we didn't anticipate."

Associate diplomatic studies Professor at the University of Oxford and head of the Oxford Digital Diplomacy Research Group Corleliu Bjola identified several methods of "online diplomacy." These include:

- Using Facebook's publicly-available option to pay for posts to be targeted at particular interest groups;

- "Gaming" Facebook's constantly changing news feed filter in order to boost page views;

- Building communities of sympathetic users more likely to reshare links or retweet and approaching other so-called influencers to do the same.

What Bjola found is that these tactics often resulted in the rapid spread of misinformation—and the likelihood of people to believe it as it was shared repeatedly within their networks. Professor Melisson said that these tactics are "getting much greater reach than through traditional media."

"In 2012 after the Arab Spring, Facebook was seen as a democratizing medium where sharing everything meant people reaching out to each other. That's still taking place but we've the same medium being used in a more intrusive way, including using algorithms not to reach the networks of your friends, like in normal public diplomacy, but to enter the networks of your opponents."

This 21st Century digital propaganda has undermined the positive power of the Internet, according to former Google executive Wael Ghonim.

"In 2011 I did say that if you want to liberate a society all you need is the Internet. However, whereas Mubarak had largely ignored the Internet, the current regime uses the Internet in a much better way—drowning out dissident voices amidst its own propaganda and also conducting a campaign of terrorizing those who speak out online. Five years ago I thought the Internet was a power that was granted to the people and that would never be weakened. But I was wrong."

Last month, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology published a study, "The Spread of True and False News Online," that analyzed how fake news and misinformation spread so quickly. Researchers found that fake news spread through social media at a substantially higher rate than real news. Most notably, the MIT team found that Twitter users retweeting false stories was largely responsible for the rapid rate at which false information blitzed social media accounts. According to MIT News, fake news stories are "70 percent more likely" to be shared than those that are true.

"The study provides a variety of ways of quantifying this phenomenon: For instance, false news stories are 70 percent more likely to be retweeted than true stories are. It also takes true stories about six times as long to reach 1,500 people as it does for false stories to reach the same number of people. When it comes to Twitter's "cascades," or unbroken retweet chains, falsehoods reach a cascade depth of 10 about 20 times faster than facts. And falsehoods are retweeted by unique users more broadly than true statements at every depth of cascade."

The study relied on Twitter as its primary source of news, focusing on 126,000 stories from 2006-2017 that were retweeted 4.5 million times by three million Twitter users. Politics was the biggest target of fake stories. The team used six fact-checking agencies (factcheck.org, hoax-slayer.com, politifact.com, snopes.org, truthorfiction.com, and urbanlegends.about.com) to determine the veracity of each story. The independent agencies agreed 95 percent of the time on what was true and what was not.

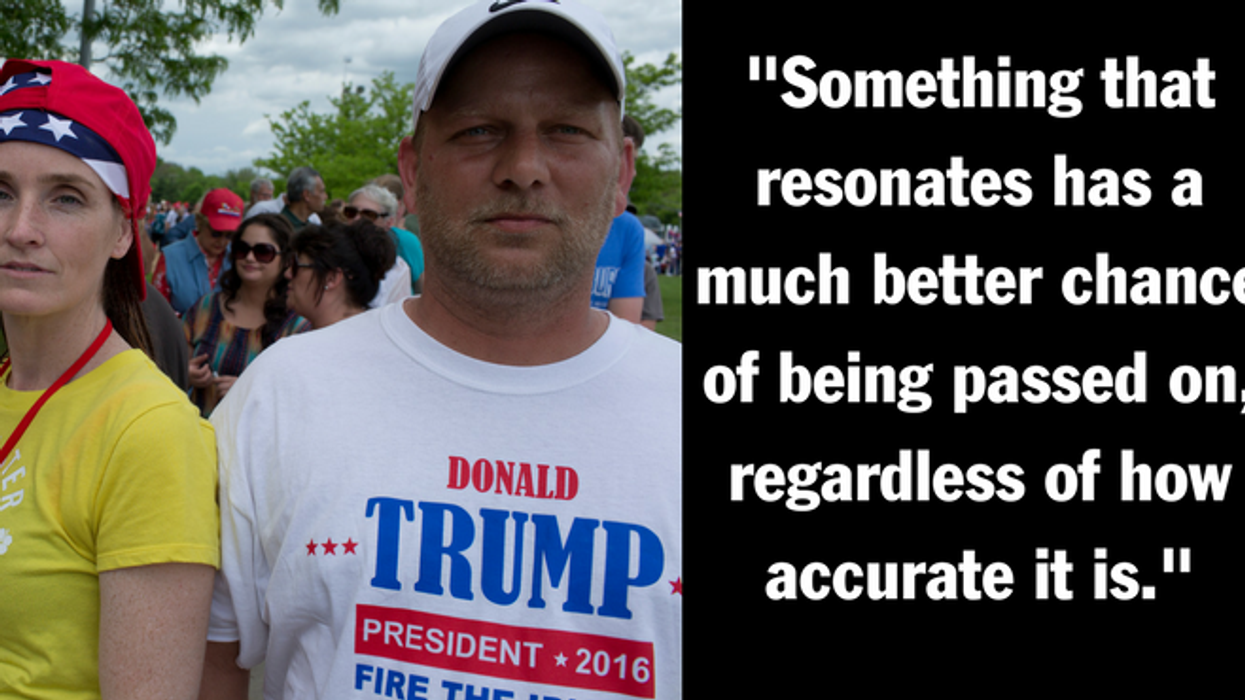

"False news is more novel, and people are more likely to share novel information," said Sinan Aral, a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management and co-author of the study. "People who share novel information are seen as being in the know." This is because people like being first to share a story no one else in their network has seen, even if that story is false. Whether a particular story was true had little bearing on how often it was shared. In fact, this resulted in fake news getting shared more often than true stories.

"We saw a different emotional profile for false news and true news," said co-author Soroush Vosoughi of Media Lab's Laboratory for Social Machines. "People respond to false news more with surprise and disgust."

@RichardLaub4/X

@RichardLaub4/X @RonFilipkowski/X

@RonFilipkowski/X

@fortunate_fiasco/Instagram

@fortunate_fiasco/Instagram @baadbrad/Instagram

@baadbrad/Instagram @starbaksh/Instagram

@starbaksh/Instagram @angelcartel/Instagram

@angelcartel/Instagram @tamoderos/Instagram

@tamoderos/Instagram @rinabekiri/Instagram

@rinabekiri/Instagram @grace.s.hamilton/Instagram

@grace.s.hamilton/Instagram @robbietomkins/Instagram

@robbietomkins/Instagram @mereyahncage/Instagram

@mereyahncage/Instagram @aristochick/Instagram

@aristochick/Instagram @rrmrrmrrmrrmrrm/Instagram

@rrmrrmrrmrrmrrm/Instagram @drewguy88/Instagram

@drewguy88/Instagram @annacollins5172024/Instagram

@annacollins5172024/Instagram @lvndrbeauty/Instagram

@lvndrbeauty/Instagram @dinalohan/Instagram

@dinalohan/Instagram

@jameelajamil/TikTok

@jameelajamil/TikTok @jameelajamil/TikTok

@jameelajamil/TikTok @jameelajamil/TikTok

@jameelajamil/TikTok @jameelajamil/TikTok

@jameelajamil/TikTok @jameelajamil/TikTok

@jameelajamil/TikTok @jameelajamil/TikTok

@jameelajamil/TikTok @jameelajamil/TikTok

@jameelajamil/TikTok @jameelajamil/TikTok

@jameelajamil/TikTok @jameelajamil/TikTok

@jameelajamil/TikTok @jameelajamil/TikTok

@jameelajamil/TikTok