A young woman whose parents were offered a termination as her “half-functioning" heart was deemed “incompatible with life" was so inspired by the NHS staff who took care of her that she has become a junior doctor.

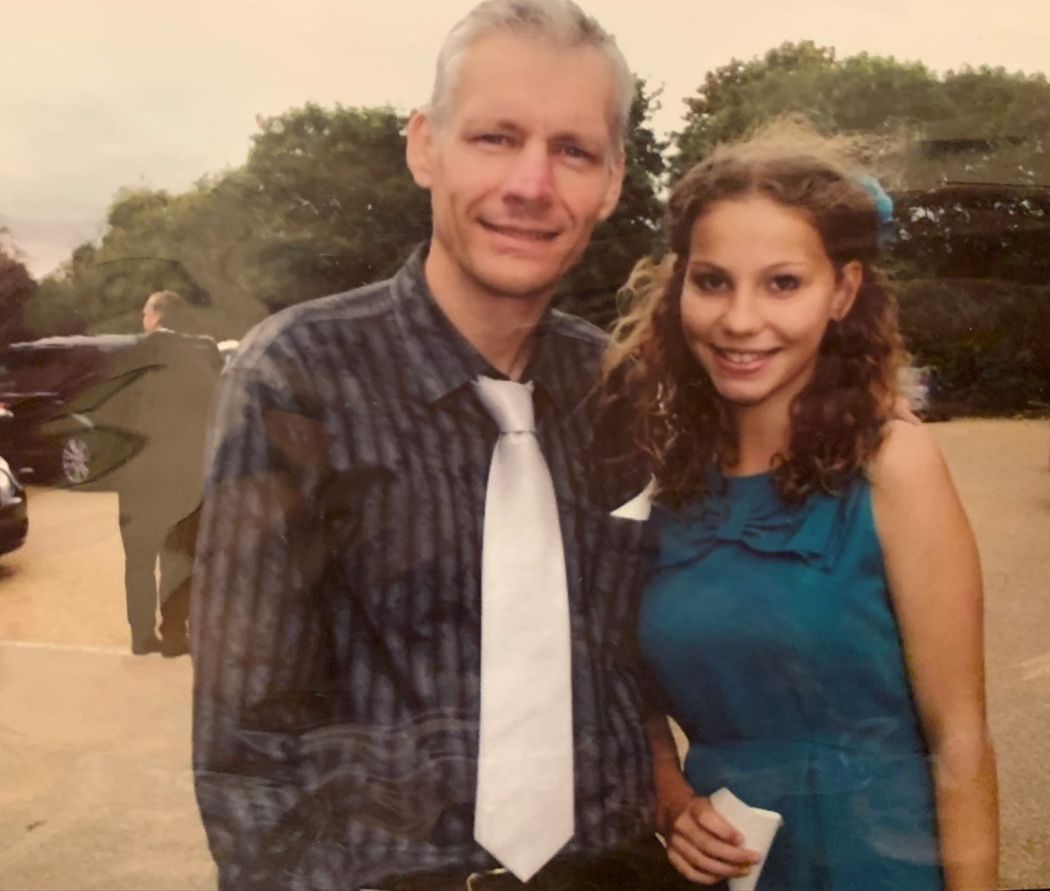

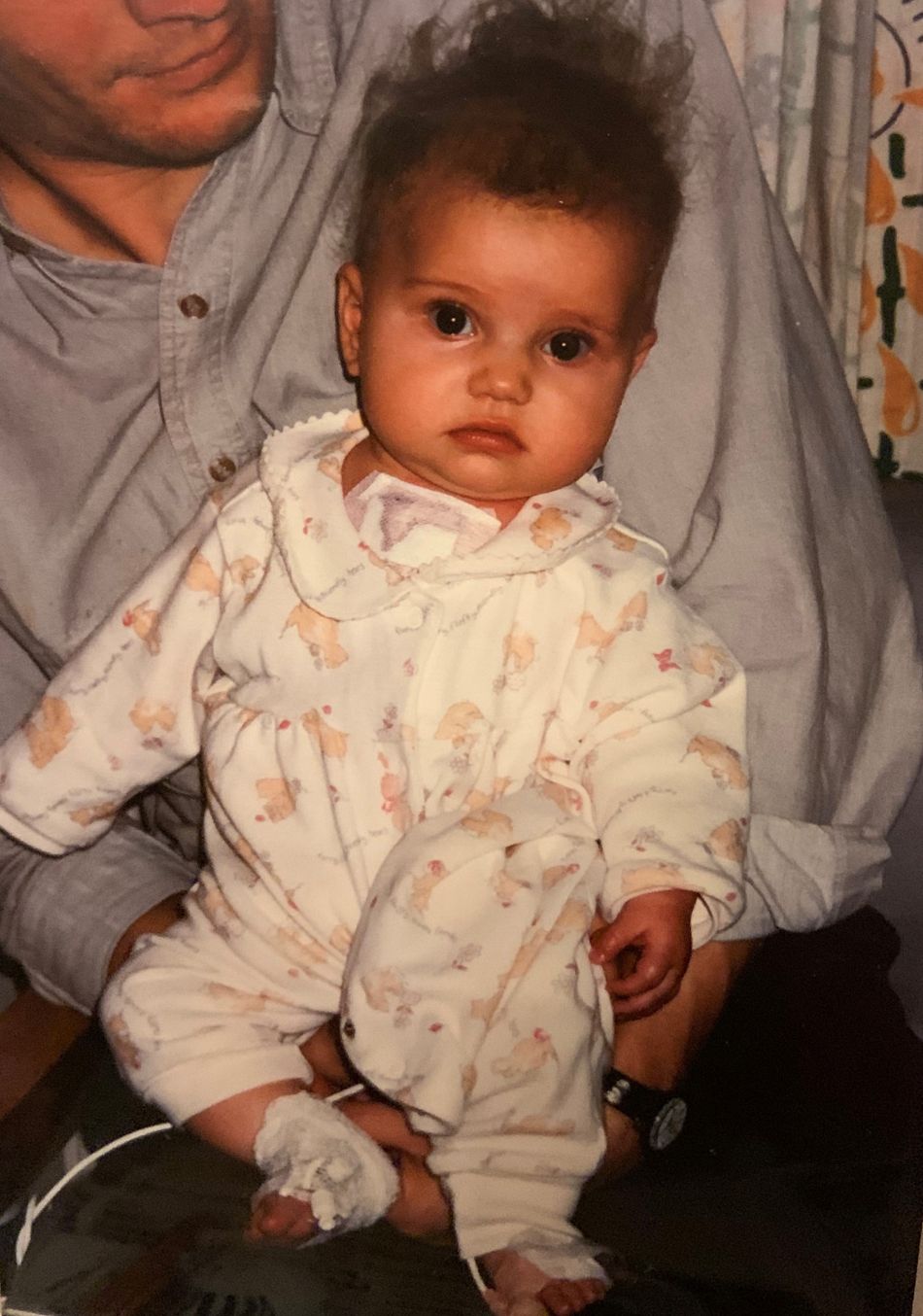

Born on June 17, 1996, with a single ventricle defect – meaning only one of the heart's pumping chambers had developed properly – Carys Allen, 24, had open heart surgery within days to save her life.

After having three open heart operations by the age of four, miraculously, Carys, of Telford, Shropshire, England, survived, but faced another uphill struggle to become a doctor, as she had dyslexia – a condition making it difficult to decode words – and was predicted below average grades.

But, applying the same dogged determination she had to her health problems, she studied relentlessly – obtaining a masters in cancer and clinical oncology at Barts Cancer Institute in London in December 2019, and then a degree in medicine at the University of Liverpool earlier this month, with a commendation.

Since graduating, Carys – who is shielding at the moment because of her heart – has secured a position at a major London hospital as a junior doctor and will start as soon as it is deemed safe for her to do so.

She said:

“When people call me Dr. Carys Allen it is so weird. I can't get my head around it – but it is still really exciting."

She added:

“Looking back on everything I've achieved, I wouldn't change my heart condition – I wouldn't go back and not be born with it."

“It's instilled me with a great work ethic and inspired me to become a doctor, which has given me this amazing opportunity."

“I wouldn't be where I am today without it."

A defiant attitude and a stubborn refusal to let her heart condition – which was first spotted at her 20-week scan – dampen her dreams, have been the key to her success, according to Carys.

“I've always been stubborn," she laughed. “I was always determined not to let my heart condition hold me back."

“If someone told me not to do something, I've always been like, 'Well I'm going to do it anyway.'"

She added:

“So, I suppose, when I realized I needed to drastically improve my grades to become a doctor, my stubbornness kicked in and I thought, 'Right, I will do this' – and I did!"

Now bravely sharing her story to raise awareness of Little Hearts Matter, the charity that has supported her and her family since the very beginning, Carys said:

“Not only did the charity help my parents before I was born, but they helped me while I was growing up to learn and understand my condition – as well as offering any emotional support I needed."

“Now, with [the pandemic], they will have much more work to do as many people with heart conditions will be shielding and many families will need support, so it's vital to share what amazing work they do."

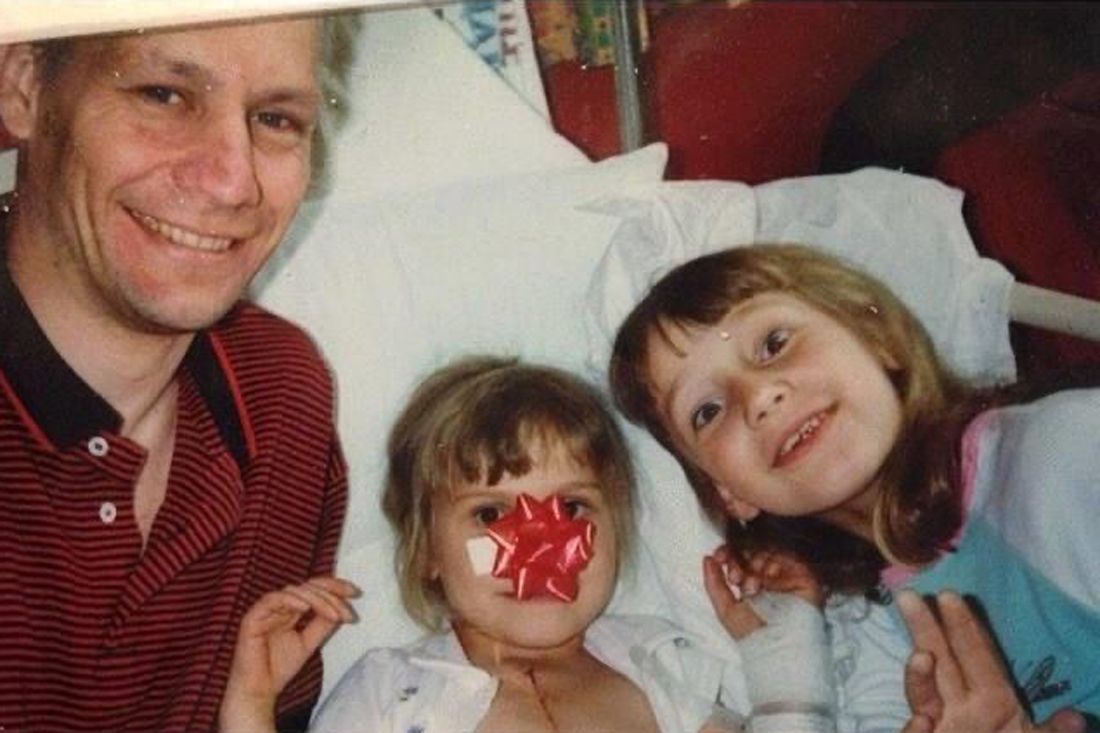

No one could be more proud of Carys' achievements than her parents, Kevin, a signal design manager and Lynn, who works in the voluntary sector, both aged 56.

They will never forget receiving the devastating news back in June 1996, at their 20-week scan, that something was seriously wrong with their unborn baby's heart.

A second scan revealed that the organ was so underdeveloped doctors deemed it “incompatible with life" and the couple were told they could either terminate the pregnancy or, if they proceeded, their daughter would need numerous open-heart operations to have any chance of survival.

“My parents were devastated but, whatever the problems, they were always going to have me," Carys said.

Around the same time, her mom and dad were introduced to Little Hearts Matter, which supports families with single ventricle defects.

She said:

“The charity was there right from the very beginning to offer advice and guidance to my parents and has helped me and my family ever since."

Put through her first open heart operation – the initial part of a Norwood procedure, designed to create normal oxygen rich blood flow in and out of the organ – at Birmingham Children's Hospital when she was just four days old, for Carys it was an early insight into the wonders performed by the NHS.

“As a newborn baby, your heart is the size of a walnut, so it's a tricky operation," she said. “But, thankfully, the surgeons did everything they could and the surgery was successful. "

Then, aged four months, she had part two of the Norwood procedure, which is regularly performed on patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome – a description for a group of the most complex cardiac defects seen in newborns, including single ventricle defects, such as Carys'.

And, aged four, she had a third open heart operation, a Fontan procedure, performed to make blood from the lower part of the body go directly to the lungs.

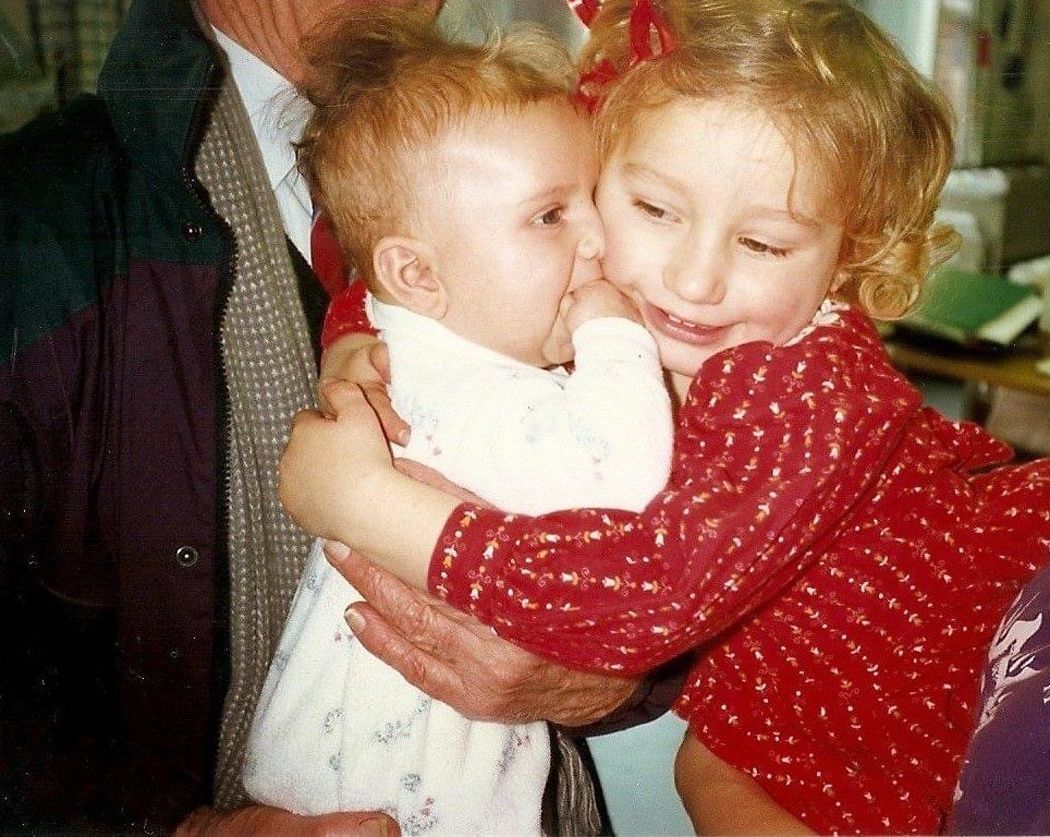

“From as far back as I can remember, I've always known I had something wrong with my heart," said Carys. “I do remember kicking up a fuss on the morning of the operation when I was four, saying I was scared and didn't want to have it."

She added:

“But my parents were brilliant at calming me down and explaining to me that it was for all the right reasons."

Carys had her final open heart surgery aged eight and, since then, has only needed minor operations to make small changes, such as putting in stents to keep coronary arteries open, as well as having check-ups and MRI scans to make sure everything is functioning.

Fortunately, she enjoyed a relatively normal childhood, although she said:

“My stamina was awful. I couldn't play tag on the playground with my friends without running out of breath."

She added:

“And on sports days it was embarrassing, because I'd always come last."

“Luckily, I never stopped taking part. I just had to resign myself to always coming last."

Since then, Carys – who exercises most days – has worked hard on her stamina, taking up ballet, tap and modern dance when she was four to help her.

“I've worked really hard over the years to improve on my fitness," she said. “Now it's a lot better than it was when I was younger. I go to the gym most days, although not at the moment, obviously, but it is something that I have to continue to work on all the time."

When she was nine, Carys hit a bad patch when her condition started to trouble her and, often feeling sick, or anxious, she did not want to go to lessons.

Worried about their daughter, her parents consulted Little Hearts Matter, who invited them all to an activity weekend in Cornwall – organized for children with heart conditions and their families.

“That weekend away was a game changer for me," said Carys. “There were so many other children there with the same condition, it made me feel normal, which was a huge relief."

“After that my anxiety got a lot better. I made some really close friends on that trip who I'm still mates with to this day."

After spending a lot of her young life in and out of hospital, Carys became fond of the play therapists who kept her company while she recuperated – deciding that was what she wanted to be when she grew up.

“The play therapists had actually made my time in hospital fun," she recalled. “I looked forward to seeing them and I liked all the attention."

“It made me want to work with children in hospital, to make their time a little easier."

But when she reached 15 and someone suggested she should become a doctor instead, Carys realized this would be her ultimate dream.

“I didn't think you could just 'become a doctor,'" she said. “I thought being a doctor was something out of my reach and hadn't really thought it was an option for me. So, when it was suggested, I was like, 'Why not?'"

"I loved the idea of being able to help people, especially children, in the same way that doctors had helped me."

But becoming a doctor looked beyond her reach when Carys was predicted a mixture of Cs and Ds in every subject at GCSE, besides science, for which she was predicted Bs, instead of the As she needed.

She said:

“I have dyslexia, so at school I found it difficult to concentrate and just let things go over my head."

“I didn't try too hard, either, and was pretty chatty in class. I certainly wasn't a teacher's pet."

But all that changed when qualifying as a doctor became her focus.

“I researched the grades I needed to get to get into medical school – it was all As," she said. “I knew it would be hard, but from that moment, I had a one-track mind, I had this fire in my belly and I was like, 'Right, I'm going to do this, I'm going to become a doctor!'"

Returning from her summer holidays in year 10, Carys' attitude changed entirely.

“I did a complete U-turn. I wasn't this chatty, annoying student anymore, all I wanted to do was study, study, study," she said.

“I was really lucky as my mum bought me all the revision books I needed and paid for a maths tutor, because I was rubbish at maths."

“But I really knuckled down and studied. I think my newfound work ethic and academic ability surprised my teachers."

The day of her GCSE results came and Carys was full of anxiety.

But she achieved her goal – obtaining 6A* and 5A grades – meaning she could go on to study biology, chemistry and English language at A Level.

Motivated by her GCSE success, she continued to study hard and two years later had obtained two A*s and an A at A Level – securing her a place at the University of Liverpool to study medicine.

“I was over the moon, it was like all my dreams had come true, as I knew I had high enough grades to get into medical school," she said.

Then, in 2018, Carys took a year out to study for her masters at Barts Cancer Institute in London, then returning to Liverpool to complete her medicine degree in August 2019, before graduating this year.

And, as part of her studies, in January this year she watched an open heart operation at Alder Hey Children's Hospital, in Liverpool, for the first time.

“I was intrigued to see an open heart operation," she said. “When I watched it I was a little bit sentimental, because it was weird knowing that I was once that patient all those years ago."

She added:

“It was really interesting to see, but I would never specialize in cardiology because it's a little too close to home."

On June 8, Carys graduated from medical school but admits it was bittersweet moment, as due to the lockdown imposed by the pandemic, the ceremony took place over Zoom.

She said:

“10 years ago I'd decided to become a doctor and I wanted to celebrate finally being able to achieve that so, in some ways, it was a bit of an anti-climax having the ceremony on Zoom."

She added:

“It was still a lovely day, though, and I had a barbecue in the garden with my family afterwards to celebrate."

And unlike most junior doctors, who have started work early due to the pandemic, Carys has been unable to, as she needs to isolate due to her heart condition.

“Lockdown has been very up and down for me, it's horrible to be a high risk person," she said.

“When the pandemic happened, immediately, I wanted to volunteer to help, I was like, 'Right, sign me up.'"

“But my cardiologist firmly told me, 'No way are you doing that,' so, I've had to isolate."

“It can be frustrating, wanting to help but not being able to."

While she has to remain at home for now, when it is deemed safe enough, Carys has already secured herself a job as a junior doctor at a major London hospital.

“It depends what happens with the virus as to when I can start," she said.

“But as soon as I can, I will. I feel so lucky that I've been able to secure such an amazing job and that I can live life to the full."

She concluded:

“I still have some worries about how my condition will affect me in the future which [the pandemic] has obviously exacerbated."

“But I try not to think about it. I try and live every day as best I can."

“Right now, I just can't wait to start my job so I can one day help others in the same way the doctors helped me."

Suzie Hutchinson, CEO of Little Hearts Matter says:

“Over two decades ago I met Carys' parents. They had just found out their unborn child had a complex heart condition and would need treatment for all of her life."

“Over the years, I've seen Carys speak out for our charity and other young people with non-correctable heart conditions like hers."

“[The pandemic] will delay the start of her work on the wards, but I know she's itching to get out there and practice medicine."

She added:

“I am so incredibly proud of her as I've been alongside her for every step of her half-a-heart journey."

To find out more visit: https://www.lhm.org.uk/

@TweetforAnnaNAFO/X

@TweetforAnnaNAFO/X

Steve Urkel Oops GIF

Steve Urkel Oops GIF  Moon Walk Dance GIF

Moon Walk Dance GIF  The Office Monday GIF by 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment

The Office Monday GIF by 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment