As people gathered around a table laden with traditional Thanksgiving fair with a nod to a treasured myth drawn from United States history, the same foods appeared on many tables as part of that same tradition.

But how accurate is turkey, mashed potatoes, gravy, cranberries, pumpkin pie and all the various side dishes?

That's something Indigenous chef Sherry Pocknett wants to teach people. The Wampanoag chef serves authentic traditional fare at her restaurant Sly Fox Den Too in Charlestown, Rhode Island.

Pocknett named her restaurant for her fisherman and Indigenous rights advocate Father, Chief Sly Fox.

All her life, Pocknett has eaten from the land of her ancestors—going frogging, fishing, foraging for wild berries and mushrooms, digging clams. Pocknett uses her Wampanoag heritage to change the way people think about traditional North American food.

She recently spoke to Rhode Island Public Broadcasting about her menu—which focuses on East Coast Indigenous cuisine—and her culture.

The Wampanoag—also known as the People of the First Light—inhabited present day Massachusetts and Eastern Rhode Island for more than 12,000 years.

At the time of their first contact with the English in the 17th century, the Wampanoag were a large confederation of at least 24 recorded tribes. Now two tribes remain—Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe and the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah).

The tribe is probably best known for feeding the Pilgrims.

But turkey is not on the menu at Sly Fox Den Too. Pocknett said her people do eat turkey, but also respect the birds for their intelligence. Wampanoag and other Eastern Woodlands tribes use turkey feathers in their regalia as a sign of that respect.

Her menu features the food Pocknett grew up with.

The Indigenous chef features what’s local and what’s in season. In the fall, that means foods like rabbit and quahogs—hard-shell clams native to the Atlantic coast.

Their restaurant's menu—and a feast for the Pilgrims—also feature duck and venison. A Pocknett family member is the hunter for the deer and Pocknett can skin and butcher it herself—a skill passed down through the women in most North American tribes.

Another staple of Indigenous cuisine is corn.

For the Wampanoag this included “journey cakes”—cornmeal patties with dried cranberries. The tortilla or pancake like patties get their name from their portability. They enjoy a long history as road-trip food.

Pocknett uses foods that grow wild on the Wampanoag homelands, like beach plums harvested on Martha’s Vineyard. The chef stews them to make sauces for the meats she served.

Many of the fruits, vegetables and other flora Indigenous peoples gathered from the land were replaced in the North American diet by seed crops brought by colonizers then settlers. But things like beach plums, high bush cranberries, choke cherries and bread root still grow wild.

Pocknett explained people don’t realize native plants are edible and delicious. Many go unpicked, left to rot on the stem or turned into food by birds, deer, bears and other foraging fauna.

But pockets of populations still harvest these traditional foods. Every spring across northern Maine roadside stands appear selling fiddleheads. Picked by hand on riverbanks and along streams shortly after the snow melts, fiddleheads were part of the Eastern Woodlands tribes diet.

Fiddleheads are the furled fronds of a young fern. Different ferns were eaten in different regions, but all are called fiddleheads for their resemblance to the top of a fiddle. Grocery stores and restaurants in the area buy fiddleheads too for a seasonal addition to their wares.

On the plains, people forage each summer for thíŋpsiŋla, also called prairie turnip or bread root. South Dakota businesses like the Prairie's Edge trading post buy the excess harvest from local foragers.

One of the most successful traditional harvests takes place in the northern wetlands region where wild rice is harvested from wild plants growing mainly in Wisconsin and Minnesota.

Pocknett also serves pinch pots full of iced tea made from boiled sassafras roots picked from behind her restaurant. This common North American tree was once the key ingredient in root beer.

Pocknett's menu reflects many of the foods that would have appeared on a 1621 feast supplied to the Pilgrims by the Wampanoag.

Historian David Silverman’s book This Land Is Their Land noted waterfowl like duck and geese, venison, cornmeal, fresh water fish like trout and ocean going Atlantic salmon and various seafood including clams, mussels and lobster would have been on the table.

Pocknett's restaurant—opened in June of 2021—joins a handful of successful eateries specializing in modern interpretations of Indigenous cuisine.

Oglala Lakota chef Sean Sherman—owner of Minneapolis fine dining restaurant Owamni—won the James Beard Award for Best New Restaurant.

The success of these businesses comes in spite of some unique obstacles.

Sherman—known online by the play on words the Sioux Chef (sous chef)—said:

"We’ve lost a lot of our own resources, especially when it comes to land-ownership and a lot of us coming out of the reservations are coming from poor communities."

While Pocknett has a wealth of stories to tell, every November customers ask about Thanksgiving.

The national holiday is complicated for Indigenous people.

Harvest and pre-Winter feasts and festivals as well as ceremonies of giving thanks are traditional around the world. Indigenous North American cultures are no different.

But the holiday born out of a post Civil War push for unity gave rise to a mythical peaceful coexistence between the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims and the colonizers that followed them.

The reality for the Indigenous people of Massachusetts and all of North America was very different than the myth taught in schools across the United States.

Pocknett shares the reality the Wampanoag faced when asked about Thanksgiving.

"We are a loving, giving people."

"We helped them, and then look what happened."

“They took everything from us and killed us. We got wiped out."

However the attempted genocide of Indigenous people isn't the end of the story.

"But not all the way. We’re still here."

"We’ve been here for over 12,000 years."

"We ain’t going nowhere."

You can try Pocknett's corn cake recipe yourself.

CORN CAKE RECIPE

Ingredients

2 cups of corn meal

1 cup of flour

2 teaspoons of baking powder

1 teaspoon of baking soda

1 tablespoon of salt

1 tablespoon of cracked black pepper

1 bunch of scallion greens chopped

1 cup of sundried cranberries

1 cup of corn (fresh cut off the cob or frozen)

1 cup of sunflower oil

1 to 2 cups of hot water

Preparation

Combine all ingredients with the exception of the water and mix well. Add water 1 cup at a time so that the mixture has the consistency of a thick hot cereal. Ladle the mix onto a hot griddle covered with sunflower oil and cook the cakes until golden brown on both sides.

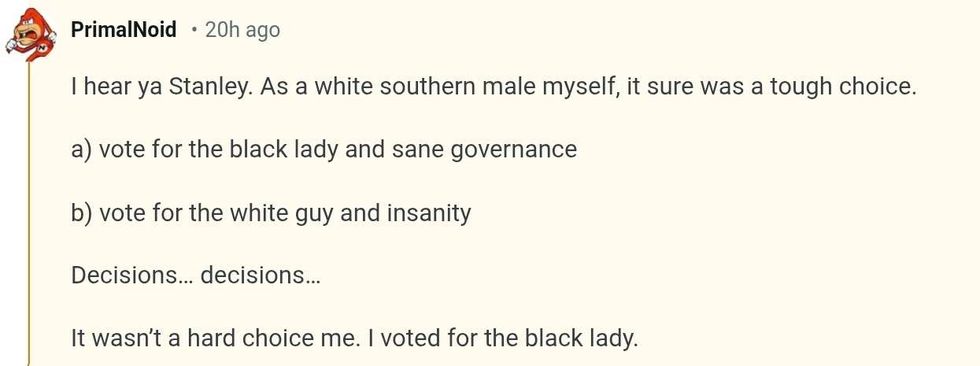

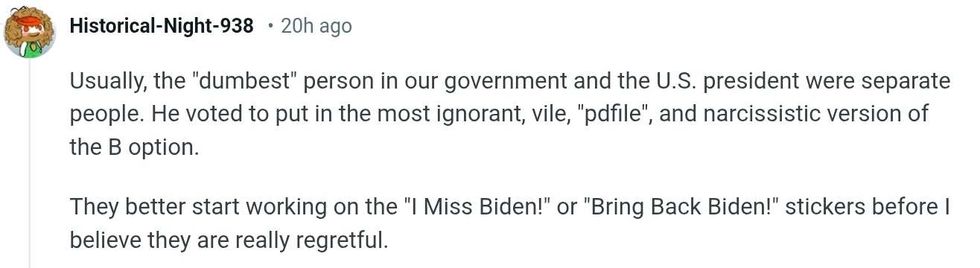

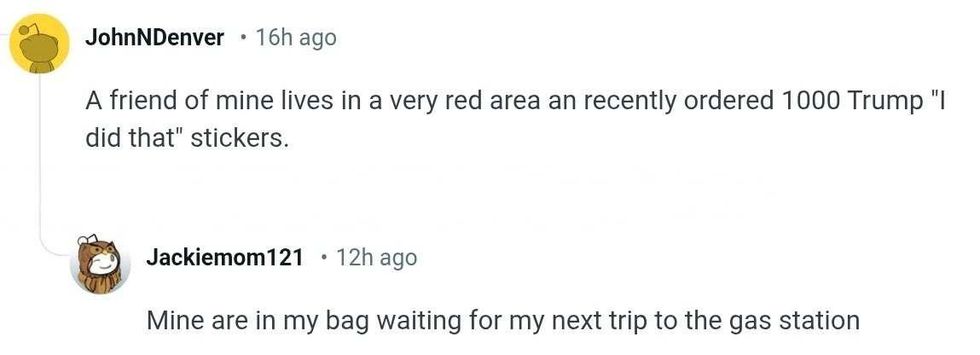

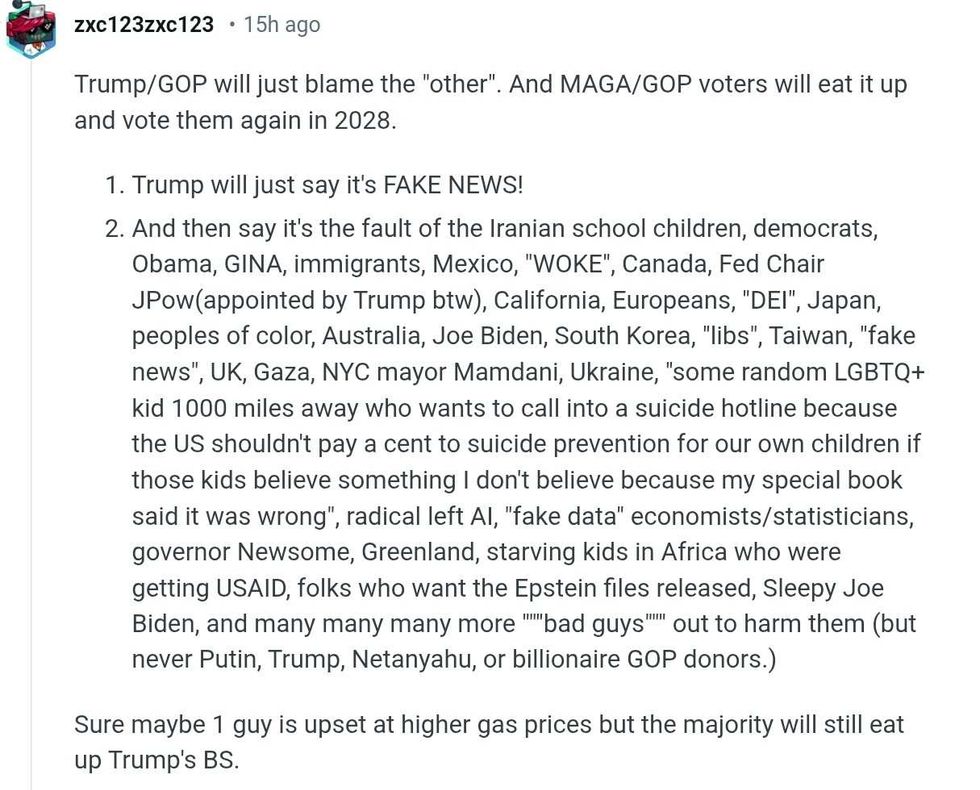

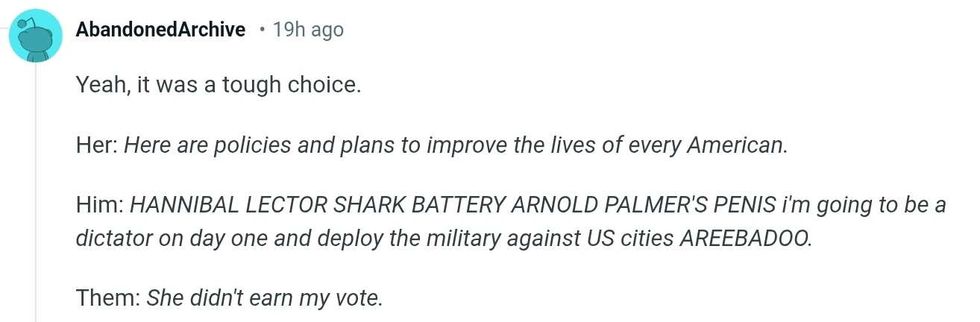

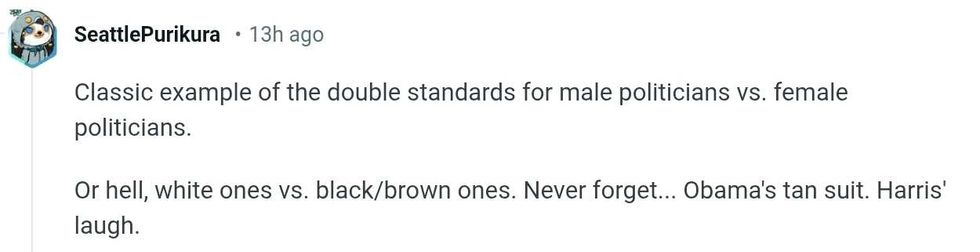

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

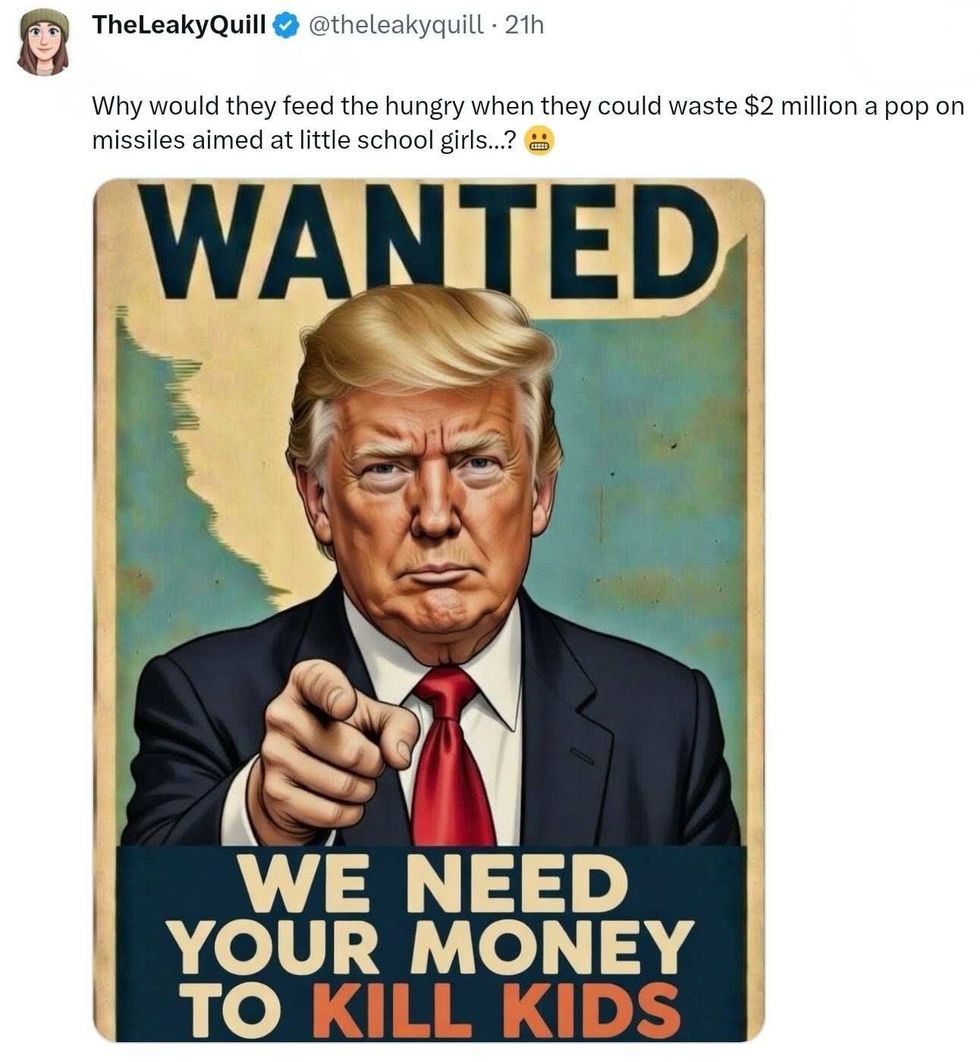

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit @theleakyquill/X

@theleakyquill/X r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit @IsabelM31530319/X

@IsabelM31530319/X r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit @cwyyell/X

@cwyyell/X r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

r/LeopardsAteMyFace/Reddit

@newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok @newsweek/TikTok

@newsweek/TikTok

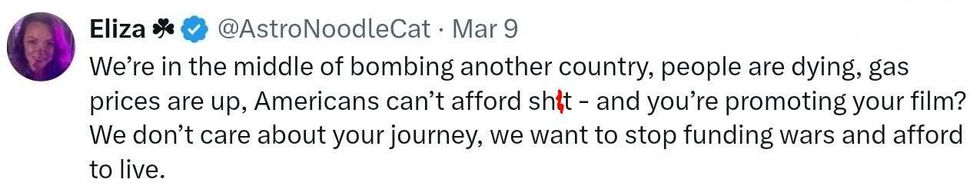

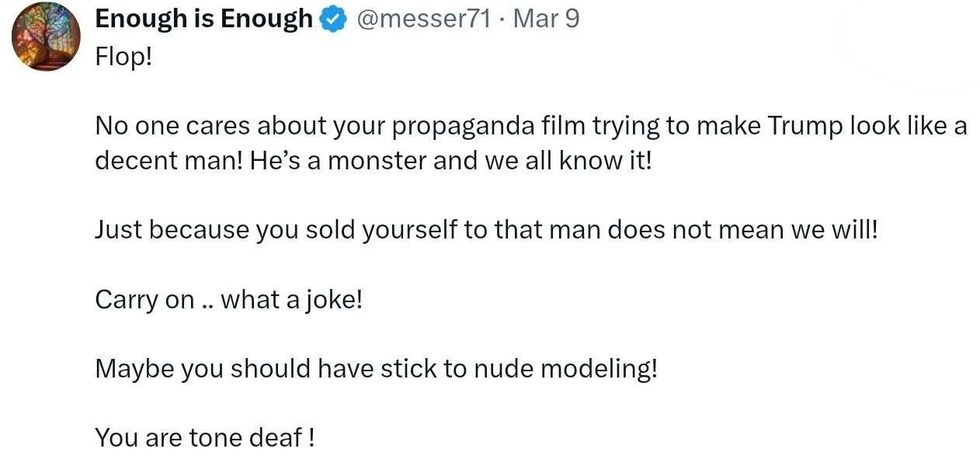

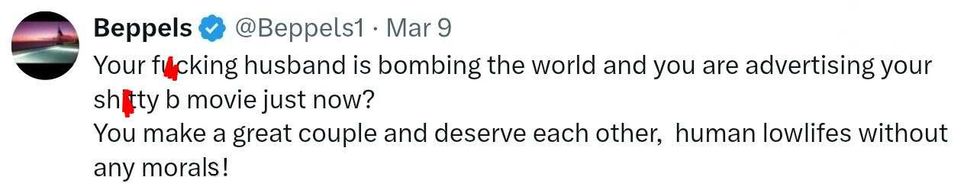

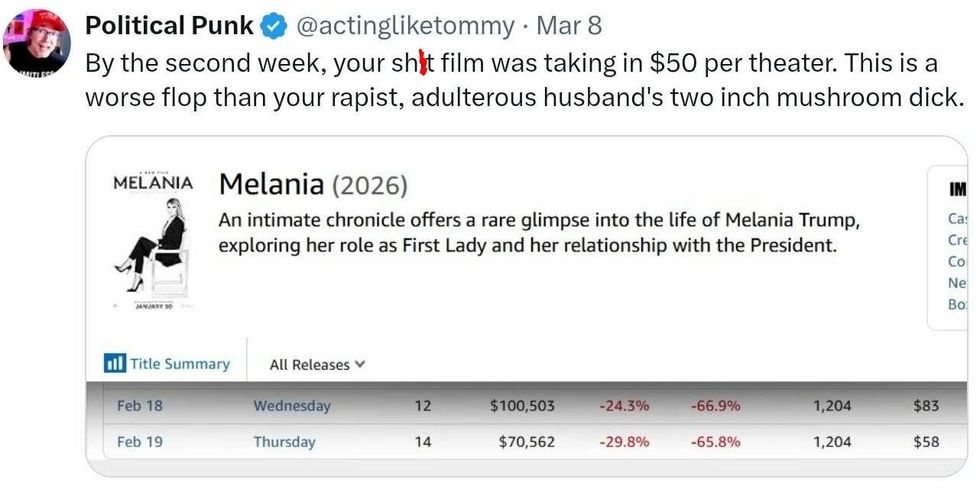

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X

reply to @MELANIATRUMP/X