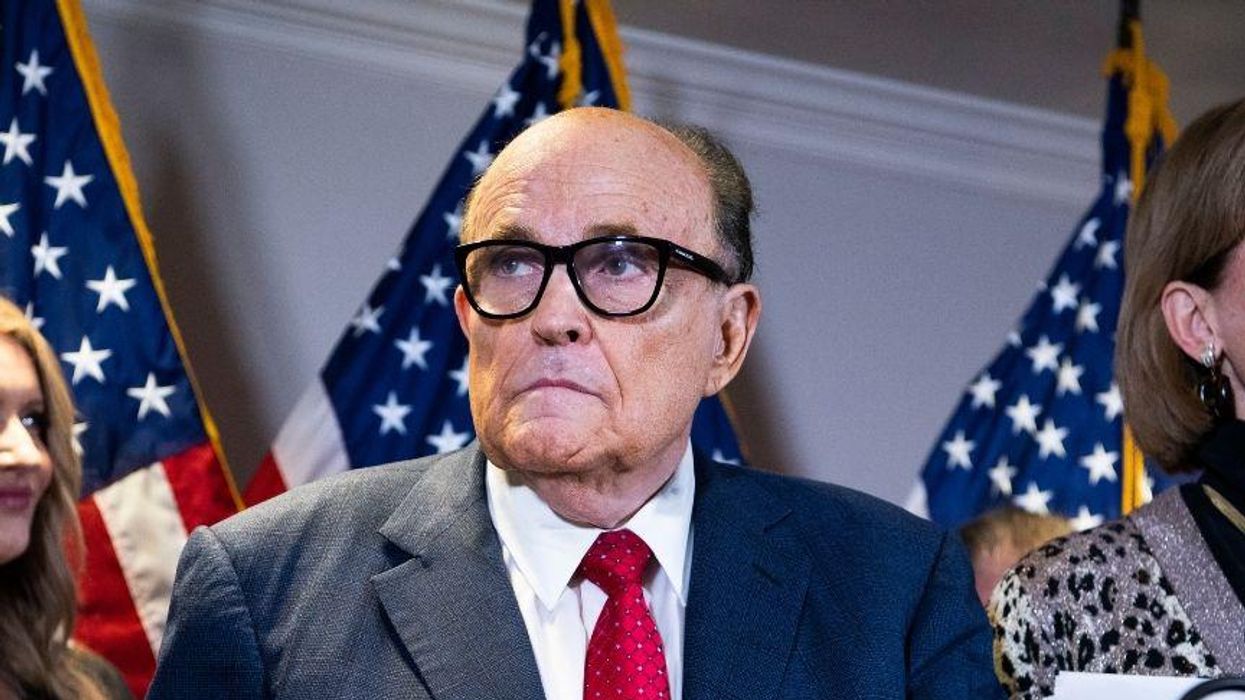

When federal agents raided the home and office of Trump's personal attorney Rudy Giuliani, America had a déjà vu moment. After all, this was now the second personal attorney of Trump whose residence was searched and whose electronic devices were seized by authorities, the first being Michael Cohen back in 2018. That is remarkable, and a very big deal, for at least three reasons that help us understand what is really going on.

First, it is incredibly difficult and dicey to serve a search warrant on an attorney. It's almost certain that evidence about his clients would also be seized, which in this case include none other than the former president. Judges are generally wary of searches on attorneys precisely because they can be used as an improper end-run around going after the suspect directly. If overused, it would damage the sanctity of the attorney-client relationship, which requires frank and open communication. If defendants believed their attorneys could be used against them, the argument goes, they would refrain from communications with them, undermining our adversarial legal system.

Generally, a search warrant may issue when prosecutors convince a judge that there is "probable cause" to believe that criminal activity is occurring at the location, or that evidence of criminal activity would be found there. That means that there are affidavits by investigators laying out what they think Giuliani has done that comprises a federal crime, and that his electronic devices (laptops, phones, tablets) may hold evidence of it. It also means a magistrate or judge has reviewed these affidavits and agreed that probable cause exists.

But because Giuliani is an attorney, the bar was set far higher. Whatever evidence is on his laptops and phones will almost certainly include or be mixed in with communications between him and his clients, which are protected by the attorney-client privilege. Further, whatever notes and other things he took (for example, with respect to the election cases) would be considered "attorney work product" and would also be protected from disclosure or use. Prosecutors would have had to convince the judge that they have a way to wall off whoever is going to sort through all this evidence so that no privileged matters are disclosed. Judges are usually skeptical that such walling-off procedures can adequately safeguard against disclosure of privileged materials.

There is an exception to the attorney-client privilege, though, and it's an important one here, just as it was with Michael Cohen.

When the attorney himself is involved in a crime, rather than just representing an alleged criminal, the privilege can be lost. Here, prosecutors are alleging that Giuliani was illegally acting as a foreign agent for his partners in Ukraine but failed to disclose this. While critics of the raid will try to paint this as a "technicality," in this case it is anything but.

In 2019, Giuliani was deeply involved in efforts to discredit Trump's main rival, Joe Biden, by smearing him with a false charge of corruption in the Burisma matter. To increase pressure on Ukraine, Trump held up military aid and made a now infamous phone call asking that the Ukrainian government "do us a favor" in investigating Biden. Put another way, Giuliani was a key liaison in a possibly illegal scheme to persuade a foreign government to interfere in our election, an act for which the former president was impeached. Had Giuliani registered as a foreign agent as required, his cover would have been blown. His failure to do so is precisely the kind of thing the foreign agent laws are designed to prevent.

The second remarkable but important thing concerns the timing of this raid. It caught many by surprise, but in hind sight it makes perfect sense. Prosecutors have been trying for months to get the Department of Justice to approve the Giuliani warrant. During the Trump administration, this request was blocked by higher-ups at Justice, but there may be a non-nefarious reason for this. It is Department policy not to undertake high profile enforcement actions so close to an election, for fear it would be perceived as putting a thumb on the scale. FBI Director James Comey's October 2016 announcement that they were reopening the Hillary Clinton email investigation was a good example of how such an action can have devastating political consequences. So this likely explains why the warrant would not be approved prior to November 3, 2020.

Further, even after the election Trump was still contesting the results for months. There were lawsuits pending everywhere, with legal efforts being led by Giuliani. It is hard to see how authorities could have launched a raid on his home and office without tainting that legal process. Indeed, it might have been seen as the "deep state" seeking revenge and trying to hamstring Trump's election cases and thereby deny him a second term.

The go-ahead for the warrant was not approved until Attorney General Merrick Garland was in charge and the last of the election cases was dismissed by the Supreme Court just last week. Because they waited, there now can be no legitimate claim that the raid was in some way related to the election.

Third and finally, the raid is remarkable because it is the closest the authorities have come to Trump himself. The evidence on Giuliani's devices may directly implicate Trump in the Ukraine scandal even further than he already is. But more critically, if the authorities can put pressure on Giuliani—without the overt threat of a presidential pardon—it is conceivable that he could cooperate with prosecutors and turn state's evidence to avoid a harsher penalty.

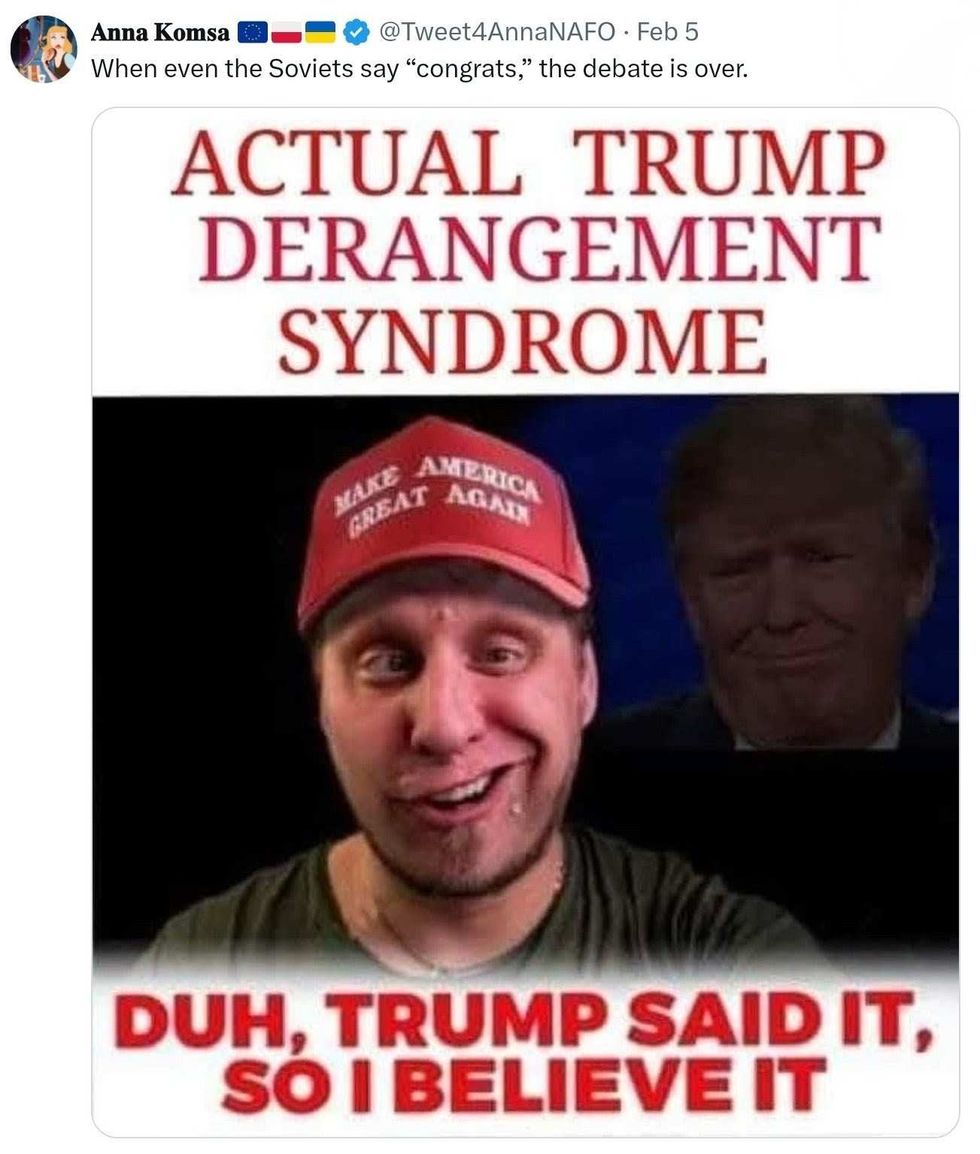

@TweetforAnnaNAFO/X

@TweetforAnnaNAFO/X

Steve Urkel Oops GIF

Steve Urkel Oops GIF  Moon Walk Dance GIF

Moon Walk Dance GIF  The Office Monday GIF by 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment

The Office Monday GIF by 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment