Who knew the next generation of social media stars would consist of giant arachnids? Recently, biologists’ use of Facebook to gain insight on the baboon spider, a mammoth tarantula species native to southern Africa, has emerged as a case study demonstrating social media’s power to transform how scientists collect data and discover new creatures.

Baboon Spiders: A Study in Crowdsourcing Scientific Discovery

Seeking to learn more about baboon spiders, researchers created a tool to collate images of the elusive eight-legger: the aptly-named Baboon Spider Atlas. The atlas, which crawls Facebook and other social media platforms in search of relevant photos, takes advantage of the public’s proclivity to post photos of particularly strange or startling creatures online.

“When people see an animal that they think is frightening or dangerous, the most common response is to take a photo and post it to social media,” explained arachnid expert and Atlas co-creator Heather Campbell of Harper Adams University. This theory could help explain why the rare tarantulas frequently show up in social media photos, despite scientists still knowing little about their habitat and behavior.

The information this project uncovered is invaluable for researchers hoping to protect these already rare spiders. Researchers responsible for the Atlas noted they “...don’t know the true distributions of many species in the region. This is the most important information needed to appreciate the value and importance of these spiders fully, and to take effective steps to conserve them.”

Screenshot via Baboon Spider Atlas.

Screenshot via Baboon Spider Atlas.

Not only did an analysis of the photos’ tagged locations increase scientists’ understanding of the species’ habitat range, but the photos also prompted them to discover dozens of apparently new species in the process. While scientists have yet to confirm their findings, they pinpointed 20 to 30 spiders that they believe are as yet unidentified, including a horn-backed spider and one with a particularly vibrant purple pigment.

Bugging Out: The Species Social Posts Casually Uncovered

The Baboon Spider Atlas stands out as a powerful instance of biologists methodically combing through social posts to obtain valuable information. Yet this is not the first example of a new species being discovered via a photo posted innocently online. In 2008, an amateur photographer stumbled upon a bright blue-and-red spider in an Australian national park: only after posting the photo on Facebook did scientists alert the man he’d snapped a shot of a totally new species of peacock spider.

Similarly, a casual researcher posted a picture of a giant carnivorous Brazilian plant, now classified as “drosera magnifica,” on Facebook in 2013. Researchers not only denoted the species as “critically endangered” and declared it “the first plant species to be recorded as being discovered through photographs on a social network," they also stressed the importance of social media as an emerging tool for discovery, emphasizing its ability to unite “amateurs and professionals in their common interests of plant identification and taxonomy.”

In a perhaps less accidental instance of discovery, a citizen scientist and professional photographer unearthed a new species of Malaysian lacewing, now known as the Semachrysa jade, when he posted a picture of the lovely green insect on Flickr in 2012 and requested feedback from natural historians. Researchers were able to find a sample of the lacewing in the wild and confirm it was an entirely new species. However, it is important to note that even the most apparently unique creature spotted on social media is not considered a member of a new species until scientists can collect and examine a physical sample, which may prove nearly impossible if the species is exceptionally rare or elusive.

Social Media: Final Frontier for Our Flora and Fauna?

Biologists and conservationists alike are only beginning to unlock a myriad of ways in which social media platforms could potentially assist in efforts to catalog, classify, and conserve flora and fauna around the globe. Social media is already a handy tool for conservationists to uncover poaching and illegal wildlife trade activity; Instagram, for its part, recently began issuing a warning to users posting hashtags that may indicate the photo involves harm to wild animals.

For now, crowdsourcing photos of local animal and plant species could soon emerge as a legitimate way for biologists to identify new species and learn more about existing ones around the world, arming researchers with tools critical to protecting our planet’s biodiversity, one spider at a time.

Happy Jennifer Aniston GIF

Happy Jennifer Aniston GIF  look ceiling GIF

look ceiling GIF  Creepy GIF

Creepy GIF  Hidden Room Loop GIF by sheepfilms

Hidden Room Loop GIF by sheepfilms

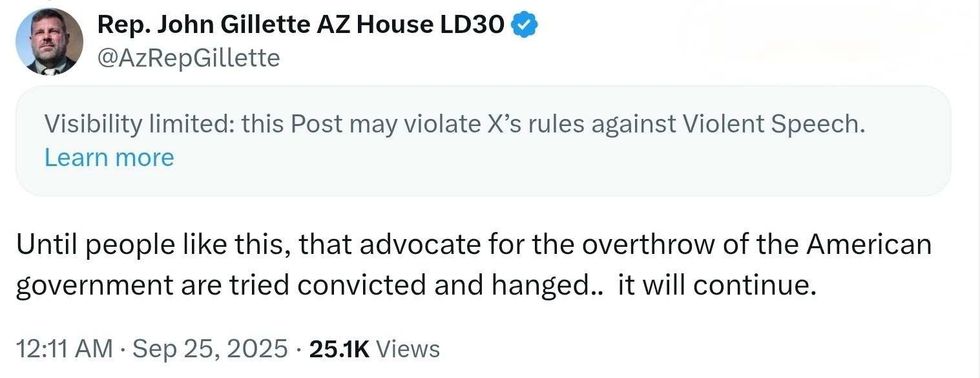

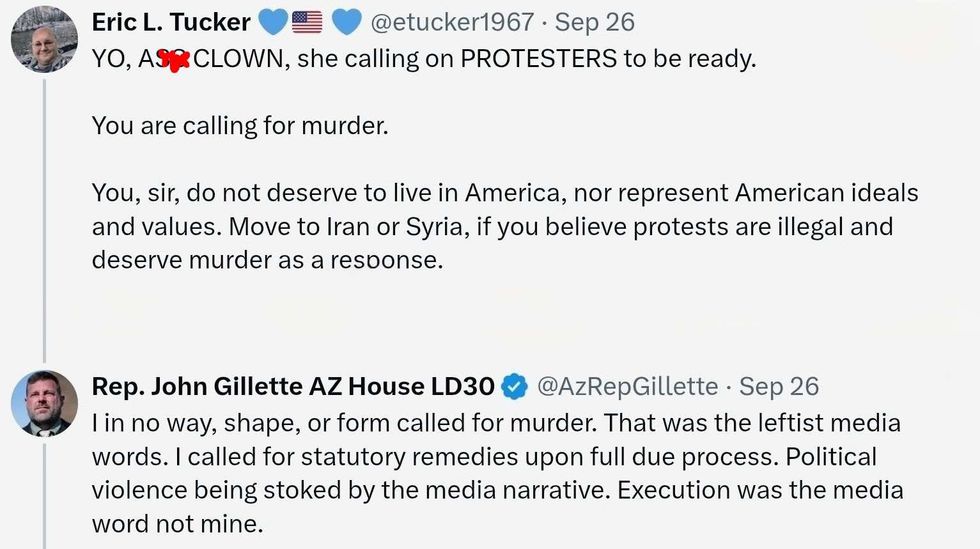

@AzRepGillette/X

@AzRepGillette/X @AzRepGillette/X

@AzRepGillette/X @AzRepGillette/X

@AzRepGillette/X

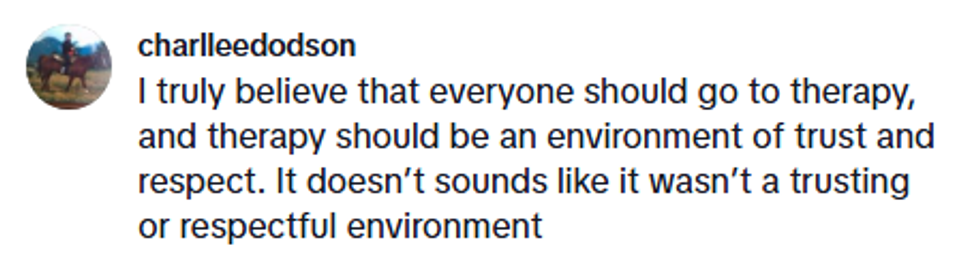

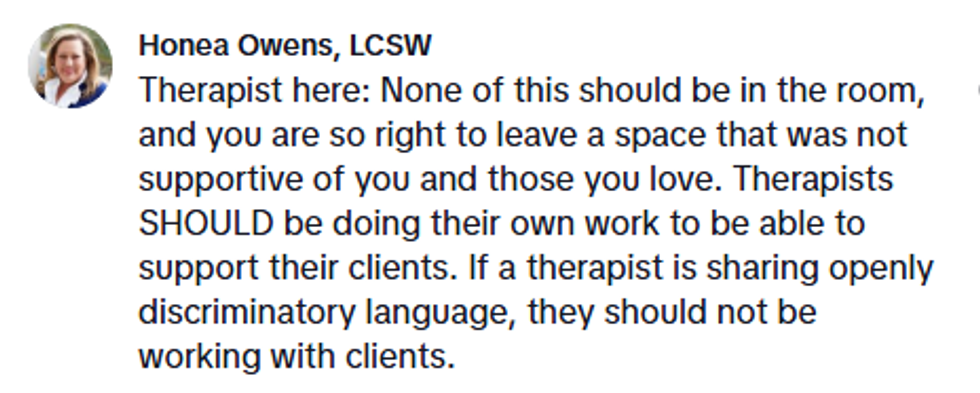

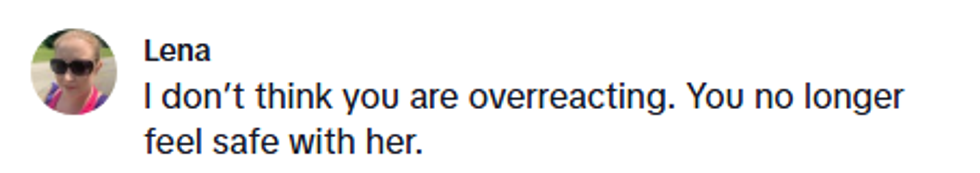

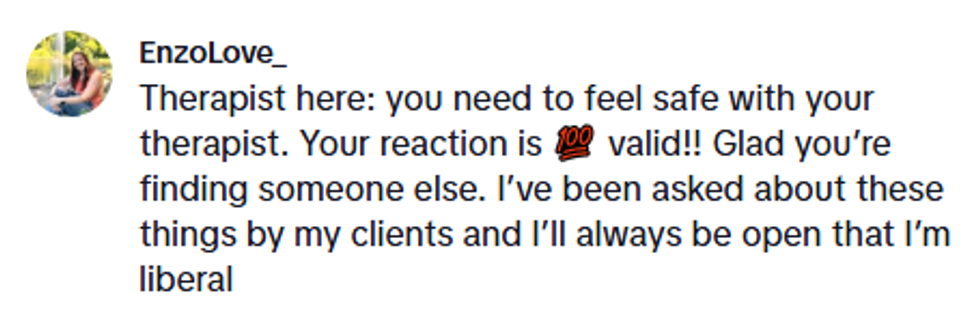

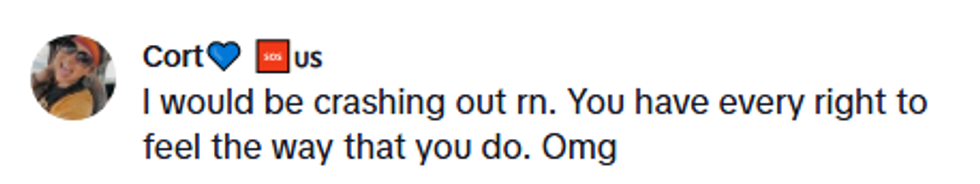

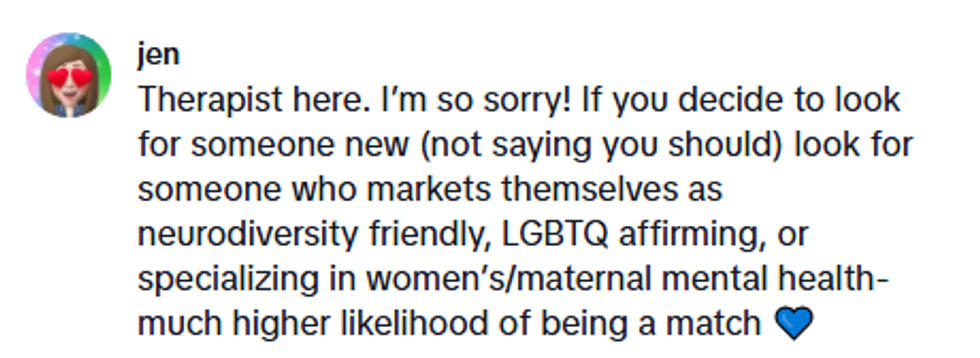

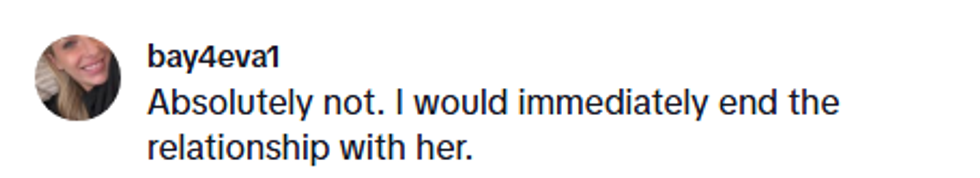

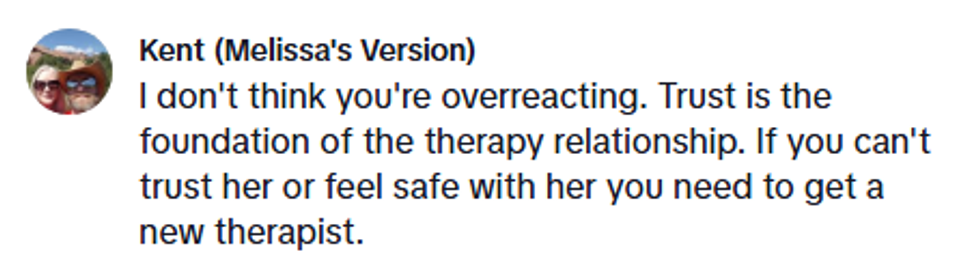

@nicolekatelynn1/TikTok

@nicolekatelynn1/TikTok @nicolekatelynn1/TikTok

@nicolekatelynn1/TikTok @nicolekatelynn1/TikTok

@nicolekatelynn1/TikTok @nicolekatelynn1/TikTok

@nicolekatelynn1/TikTok @nicolekatelynn1/TikTok

@nicolekatelynn1/TikTok @nicolekatelynn1/TikTok

@nicolekatelynn1/TikTok @nicolekatelynn1/TikTok

@nicolekatelynn1/TikTok @nicolekatelynn1/TikTok

@nicolekatelynn1/TikTok @nicolekatelynn1/TikTok

@nicolekatelynn1/TikTok @nicolekatelynn1/TikTok

@nicolekatelynn1/TikTok @nicolekatelynn1/TikTok

@nicolekatelynn1/TikTok @nicolekatelynn1/TikTok

@nicolekatelynn1/TikTok

@valerieelizabet/TikTok

@valerieelizabet/TikTok @valerieelizabet/TikTok

@valerieelizabet/TikTok @valerieelizabet/TikTok

@valerieelizabet/TikTok @valerieelizabet/TikTok

@valerieelizabet/TikTok @valerieelizabet/TikTok

@valerieelizabet/TikTok @valerieelizabet/TikTok

@valerieelizabet/TikTok @valerieelizabet/TikTok

@valerieelizabet/TikTok @valerieelizabet/TikTok

@valerieelizabet/TikTok @valerieelizabet/TikTok

@valerieelizabet/TikTok @valerieelizabet/TikTok

@valerieelizabet/TikTok @valerieelizabet/TikTok

@valerieelizabet/TikTok