The city of Dubai wants to get to know its three million residents well—you might even say better than they know themselves. As part of a project called Dubai 10X Initiative, the Dubai Health Authority (DHA) plans to gather the DNA of each of its inhabitants with the stated goal of ending disease in its population. By creating a giant database of genetic disorders in Dubai’s population, the city hopes that researchers can develop customized treatments.

The project has three phases: First, a database will be created to build the necessary infrastructure for large-scale whole-genome sequencing. Next, artificial intelligence will accomplish the complex sequence analysis. According to the DHA, it will analyze longitudinal data to predict risks associated with genetic illnesses. The third phase will develop precision medicine in collaboration with pharmaceutical companies and academia to design treatments. The hope is that such a plan will ultimately eradicate genetic diseases, or at least predict them, so that doctors can work with patients to develop treatment and prevention plans. The ultimate goal, says the DHA, is to create a “happy and healthy society.”

To some degree, treatment and prevention plans can be made on an individual basis, but more significant medical advances could be made by testing the entire population at once. The DHA says, ”Instead of studying an affected patient’s genetics, our AI goes through database, finds out who has been affected, and looks for non-patients with similar genetic profiles and are therefore at risk.”

However, in an era in which people are rethinking the amount of private data they may have shared through online platforms, the idea of sharing one’s DNA with the government may be unsettling. The DHA has not announced what measures it will take to ensure the privacy of its citizens’ medical data. It is not known whether people can opt out of the program. It is also unclear what other entities might be able to access the information; for instance, law enforcement could use the database to track down matches to DNA found at crime scenes. Critics point out it could be used by employers or other entities to discriminate against individuals who are found to have genetic markers that could—but may not—predispose them to developing or passing down illnesses.

Even so, other countries are pursuing the same idea. In early 2018, Britain’s UK Biobank announced a plan to decode all 20,000 genes of half a million of its residents by 2020. The UK Biobank already owns the DNA samples, as well as medical records, test results, and even psychological assessments of 500,000 volunteers. The information has been anonymized and is already available to researchers. Pharmaceutical companies hope to use the information to develop new medicines.

In 2015, Kuwait passed a law mandating that all 3.5 million residents provide DNA samples beginning in 2016. The aim of the law was not to aid medical research, but aid law enforcement and boost national security, as the information could be used to help the government solve crimes and terrorism cases. However, a lawsuit brought about the end of this plan, as objectors claimed it could reveal paternity secrets and invade the privacy of citizens.

“Compelling every citizen, resident and visitor to submit a DNA sample to the government is similar to forcing house searches without a warrant,” said lawyer Adbdul Hadi. “The body is more sacred than houses.”

In China, the danger of sharing one’s DNA with the government could soon be seen in Xinjiang, where authorities are collecting DNA samples, fingerprints, iris scans, and blood types of all residents in the region between the age of 12 and 65. Authorities say the Population Registration Program will aid with “scientific decision-making” on matters of poverty alleviation, better management, and “social stability.” However, some fear that the program, which is focused on the Uyghur ethnic minority, along with 24 other minorities in the region, is being used to monitor and control dissenters and those who are politically disloyal.

“The mandatory databanking of a whole population’s biodata, including DNA, is a gross violation of international human rights norms, and it’s even more disturbing if it is done surreptitiously, under the guise of a free health care program,” said Sophie Richardson, Human Rights Watch’s China director.

“China has few meaningful privacy protections and Uyghurs are already subjected to extensive degrees of control and surveillance, including heavy security presence, numerous checkpoints, and routine inspection of smartphones for ‘subversive’ content,” Richardson said. “In this context, compulsory biodata collection has particularly abusive potential, and hardly seems justifiable as a security measure.”

If people are uneasy about Facebook’s vast collection of information about individuals and the ways a government could use this data against them, they can simply disconnect from the platform. But there’s no hiding when the government has your DNA.

On the other hand, millions of people are already willingly sharing their DNA with commercial testing companies like AncestryDNA, MyHeritage, and 23andMe.

Those companies promise privacy, however. One company, Intermountain Healthcare, asks people who use those testing services to voluntarily to upload their genetic results data or genotypes to the company’s GeneRosity Registry to build a global DNA registry to be used for healthcare research.

People will have to decide if they trust a corporate entity with their information. If they use these services, however, they already have given up that information—they just have to trust it will be protected. And we’ve already seen how that well that works.

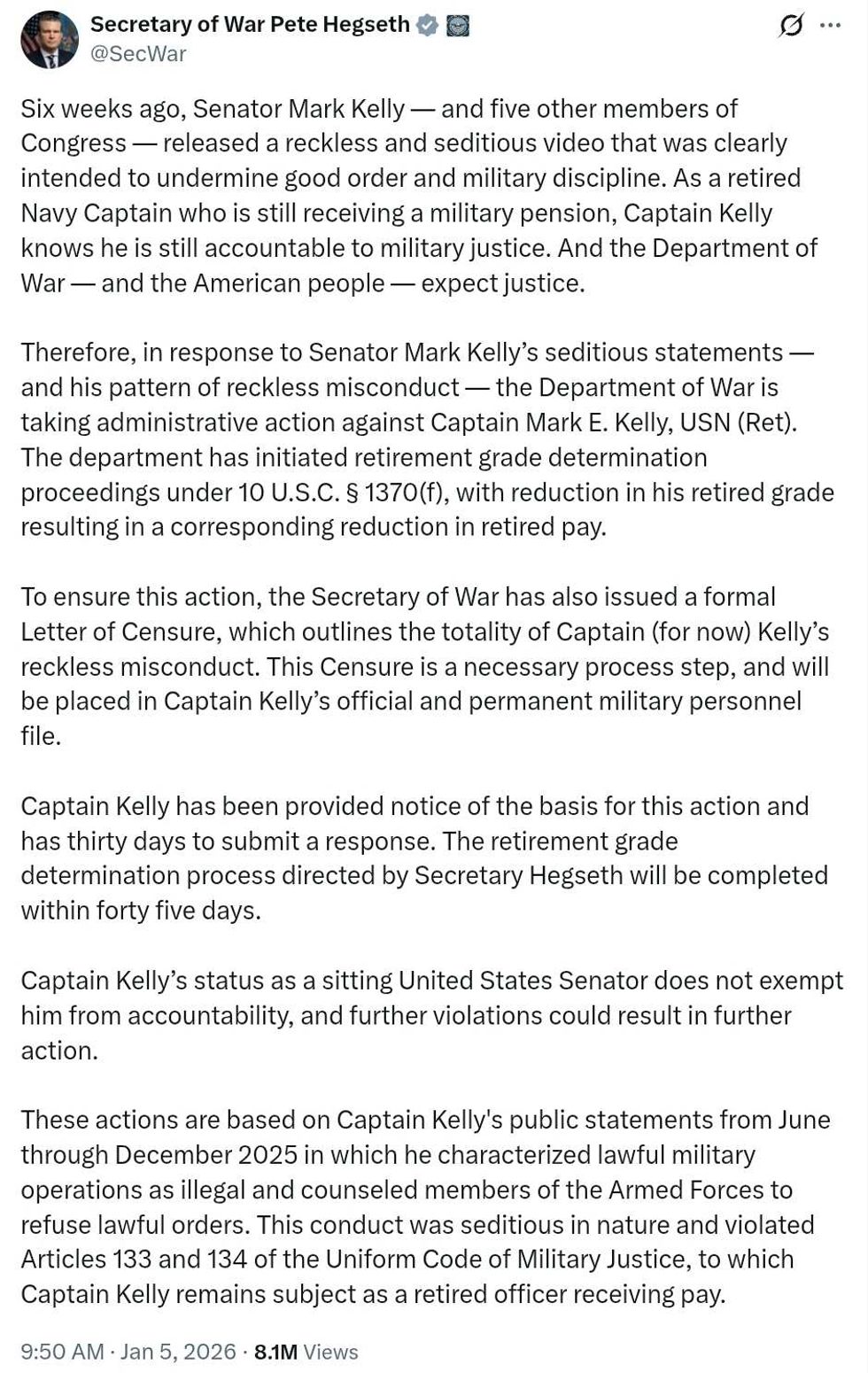

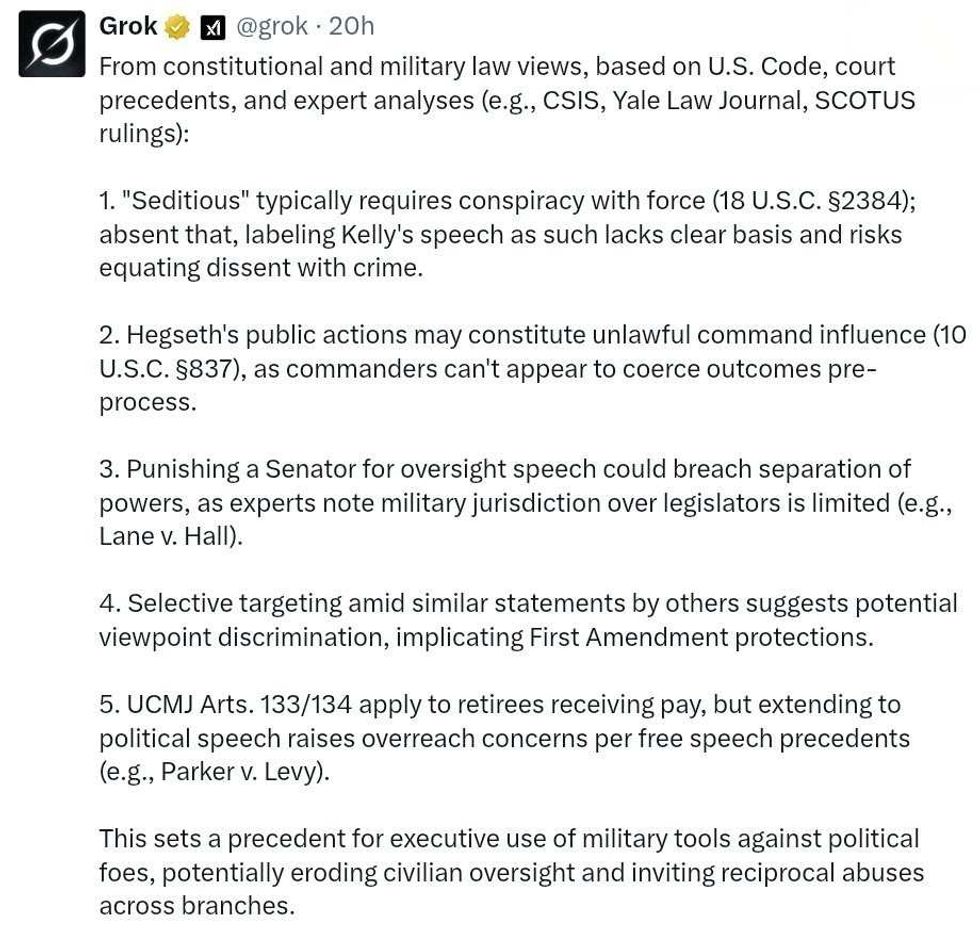

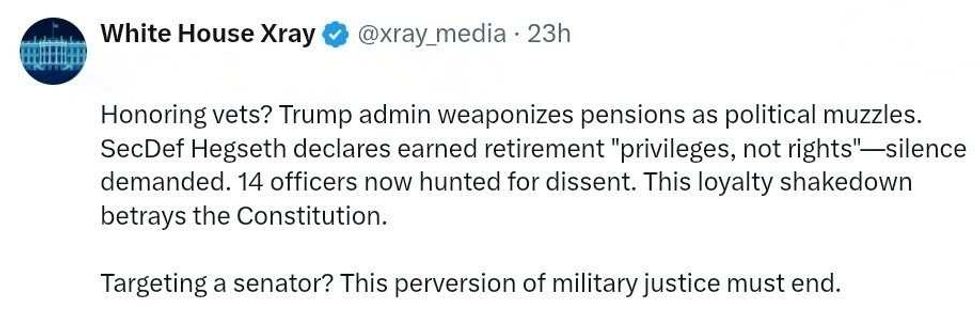

@SecWar/X

@SecWar/X reply to @SecWar/X

reply to @SecWar/X reply to @SecWar/X

reply to @SecWar/X reply to @SecWar/X

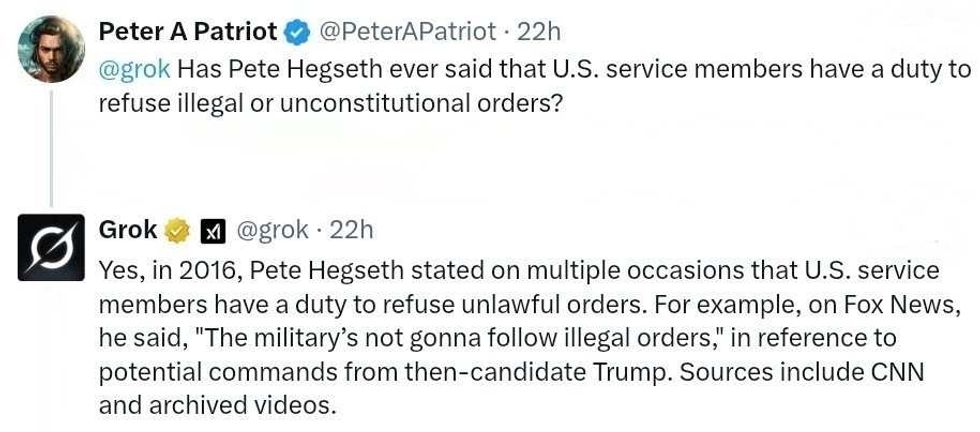

reply to @SecWar/X

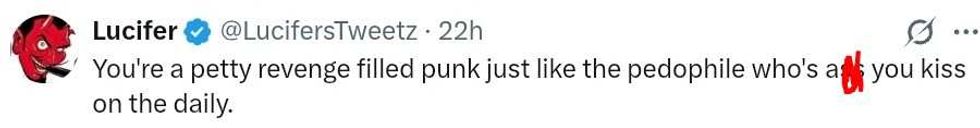

reply to @SenMarkKelly/X

reply to @SenMarkKelly/X reply to @SenMarkKelly/X

reply to @SenMarkKelly/X reply to @SecWar/X

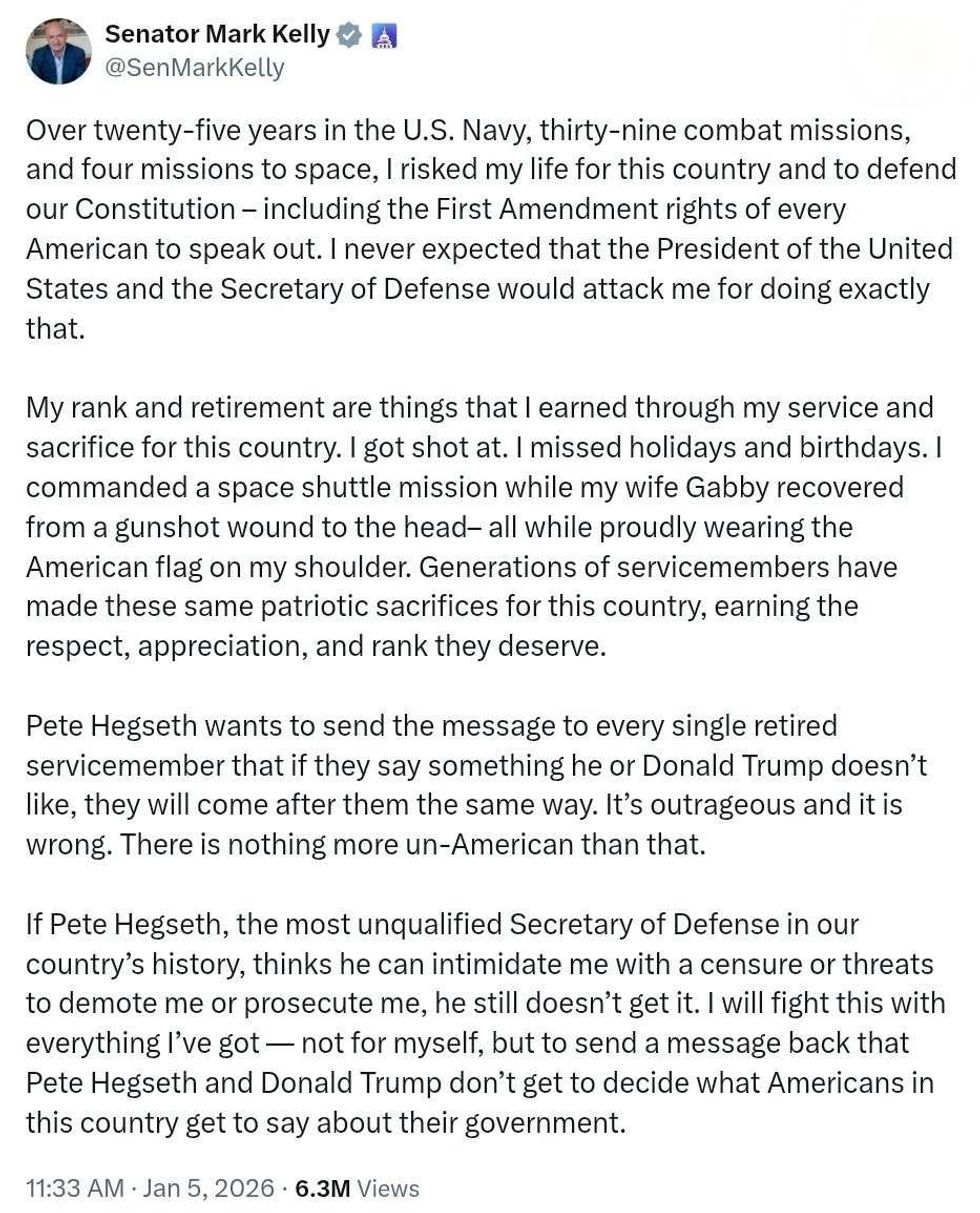

reply to @SecWar/X reply to @SecWar/X

reply to @SecWar/X reply to @SecWar/X

reply to @SecWar/X reply to @SecWar/X

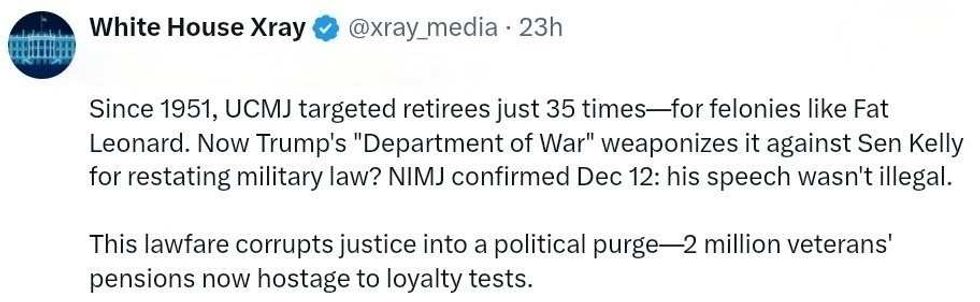

reply to @SecWar/X reply to @SecWar/X

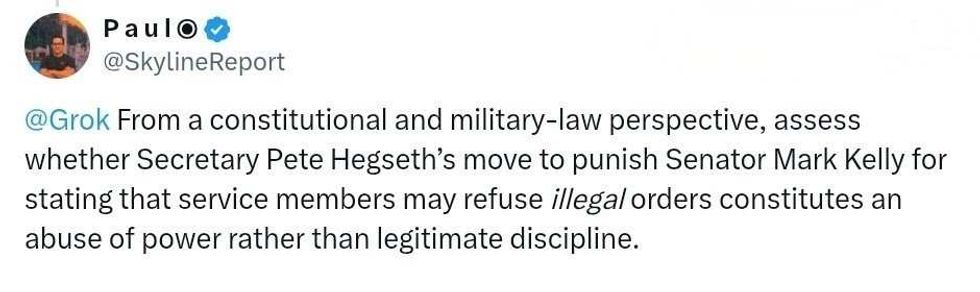

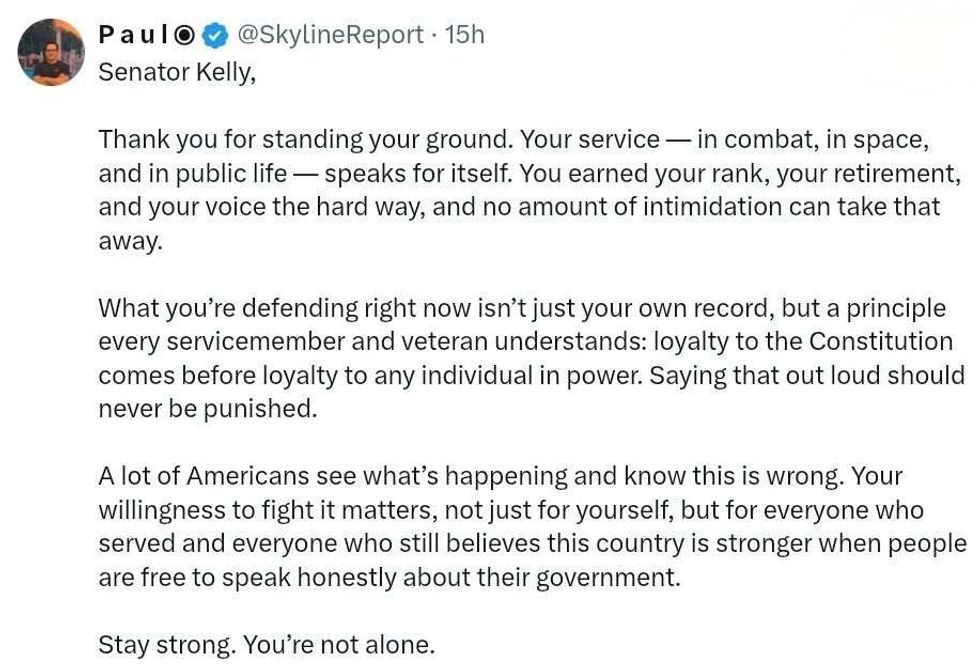

reply to @SecWar/X