With the House narrowly passing its version of President Biden's ambitious Build Back Better (BBB) social safety net and climate change legislation, all eyes are now on the Senate where its future is, at least at the moment, unclear. Two senators, Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, must get on board in order for the bill to pass with 50 Democratic votes and one tie-breaking vote from Vice President Kamala Harris. Many fear they will use their unique power in an evenly split senate to sink the bill entirely. But what are the chances of that happening?

At this point, the two have given both public statements and some private indications about where they stand. Their remaining concerns seem to boil down to three basic issues: The bill might add to inflationary pressures, the House version differs in key ways from the framework President Biden laid out, and it might not be fully paid for. Let's break these down.

Inflation Concerns

Senator Manchin repeatedly has voiced his concern that spending $1.85 trillion on top of the $1.2 trillion recently approved for infrastructure would cause prices to rise even further, which would most directly impact those who are on fixed income such as the elderly. The most recent jump in the Consumer Price Index of 6.2% for the month of October added considerable weight to these concerns. The traditional thinking goes, if people have more money to spend, prices will rise as demand for goods rises. The stakes are quite high as the White House struggles to tamp down price spikes: High inflation is currently a big economic worry among Americans and is responsible for a great deal of the administration's negative poll numbers.

The counter-argument to this points out that most of today's inflation results from supply chain issues that are being resolved and high gas prices due to deliberate supply restrictions by Saudi Arabia in retaliation for the White House's more hardline position toward the new Saudi regime, along with some evidence of collusion among energy companies to keep prices high. Lately, supply chain issues are beginning to resolve themselves, as expected, and oil prices have fallen. Gas prices, at least in a market free of manipulation, should follow.

With respect to the plan itself, two high-profile rating agencies recently sided with the White House in asserting that it would not impact inflation in the short-run and might even have an easing effect. "The bills do not add to inflation pressures, as the policies help to lift long-term economic growth via stronger productivity and labor force growth, and thus take the edge off of inflation," said Mark Zandi, the chief economist at Moody's Analytics. In addition, recent numbers out of the U.K., which saw prices rise by 4.2 percent in October, suggest that inflation is not limited to the U.S. and is indeed a global issue impacted by higher energy prices and supply chain woes.

Nevertheless, Sen. Manchin conceivably could use fears of inflation to seek a delay in the passage of BBB until there is evidence that price pressures are easing and coming down. But inflation is not an argument for doing nothing at all, ever.

The House Bill Added New Items to the Framework

Sen. Sinema has taken issue with aspects of the House bill that were not initially agreed to among House and Senate negotiators and the White House. Chief among these was the addition of paid family leave for four weeks, which bumped the overall cost of the bill higher by about $200 billion.

Then there is the controversial state-and-local tax (SALT) deduction, which the GOP capped at $10,000 in 2017 with an expiration of the cap in 2026. That cap disproportionately impacts residents who live in blue states with high-income taxes, such as California, New Jersey, and New York. Moderate Democrats in the House had insisted upon raising the cap to $80,000 for most of the decade before dropping it back to $10,000 in 2031. This plan would initially benefit largely higher-income residents in certain states, with a smaller deduction benefit later. Progressives in the Senate such as Sen. Bernie Sanders are miffed that the House bill now contains a tax break for high-income earners when it is supposed to benefit those most in need, and he may insist on its removal.

Paid family leave is likely to be one of the first casualties of the upcoming compromise. It was something negotiators had agreed to leave out of the framework on Sen. Manchin's insistence, and it's fairly expensive. The original proposal of 12 weeks had been trimmed back to four before being cut out entirely…then added back in by the House. It seems, however, that we are at an all-or-nothing moment. There's no meaningful way to cut four weeks of paid parental leave back any further without going to zero. Despite progressives' best intentions, no one should be surprised at this point if it falls out entirely.

The SALT deduction cap limit raise may also get the axe, perhaps in exchange for the loss of paid family leave. Politically, it undercuts Democratic talking points about a more level and fair taxation system. And depending on how you calculate it, the program could be deemed expensive in the short term with somewhat gimmicky sunset provisions. Should control of the government change hands in the next 10 years, for example, the drop in the cap set for 2031 could easily be nixed, leaving all the future government revenue merely theoretical while giving a big break to more wealthy households today.

Sens. Manchin and Sinema wouldn't need to do much to get their way beyond insisting on the deal that they had originally indicated they would approve, one that bore the original $1.85 trillion price tag. That seems an obvious move and likely outcome at this time.

BBB Might Not Be Fully Paid For

Earlier this month, the House had been deadlocked because a group of moderates had insisted they didn't have confidence that the CBO Report on the final cost of the bill would wind up supporting the White House's own estimates. Meanwhile, the Congressional Progressive Caucus had refused to sign onto the Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal unless they had assurances from moderates that they would back passage of BBB. The Democrats finally got around this issue by following the lead of Rep. Ted Lieu (D-CA), who suggested having the moderates sign on to a pledge to support BBB should the CBO numbers come out in line with expectations.

The CBO Report finally did emerge more or less in tune with White House estimates, and the House voted in favor of BBB on a nearly full party-line vote. The Report concurred with the White House numbers except in one key way that requires some explanation. The CBO estimated that the House bill would cost $1.7 trillion in spending and bring in $1.3 trillion in revenue over 10 years, leaving a shortfall of $400 billion. In the notes to its report, however, the CBO made clear that this figure did not include additional money from more robust IRS enforcement, which it cautioned it wasn't allowed to include due to "scorekeeping rules" but which, it believed, would raise an additional $207 billion. That left a shortfall of $193 billion.

The Treasury Department, however, believes that the actual revenues the IRS would bring in through tougher enforcement are at least $400 billion, meaning BBB is in fact fully paid for if you use the Treasury's own estimates. Some experts, including Lawrence Summers, who was an economic advisor to Presidents Obama and Clinton, believe the amount in new revenues would be at least twice this, because the amount the IRS is owed versus what it actually collects is currently a whopping $7 trillion over 10 years absent stronger enforcement.

Sens. Manchin and Sinema are less likely to take issue with the CBO shortfall (which, again, is officially at $193 billion but also could be zero, depending on whom you believe) than they are with adding back new programs such as paid family leave. After all, the CBO numbers on their Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework came in with an estimate of $256 billion added to the deficit, but that didn't lead to them suddenly start opposing the bill due to cost estimate overruns.

It's certainly possible, and a lurking concern of many progressives, that the unstated goal of one or both of these senators is to kill the bill entirely, in which case any issue they have with it could serve as a pretext for total obstruction. But this scenario seems unlikely given that a bill with a lower price tag had already been negotiated with the White House at considerable investment of time and political capital. A delay of the bill is still a risk, especially given Sen. Manchin's concerns over inflation, but actual implementation of a ten-year spending bill beginning one or two months later than planned isn't going to impact short-term inflation either way. A delay serves very little purpose other than to further sink the Democrats' poll numbers, especially among progressives who will feel betrayed by their own leaders.

With a few key provisions still to negotiate, December could become a painful repeat of this fall's many cuts to the bill, or the Senate could come back and quickly agree to it under the original framework numbers and programs. Given the urgent need to stop the slide in Biden's approval ratings and poll numbers for Congressional Democrats in the upcoming 2022 midterms, the latter course would be far more advisable. It would hand Biden three major legislative victories in his first year in office, achieved with just razor-thin majorities in both chambers of Congress. By contrast, former President Trump and his party only achieved one major bill—a tax cut for the wealthy and corporations that added $1.9 trillion to the deficit.

For more political analysis, check out the Status Kuo newsletter.

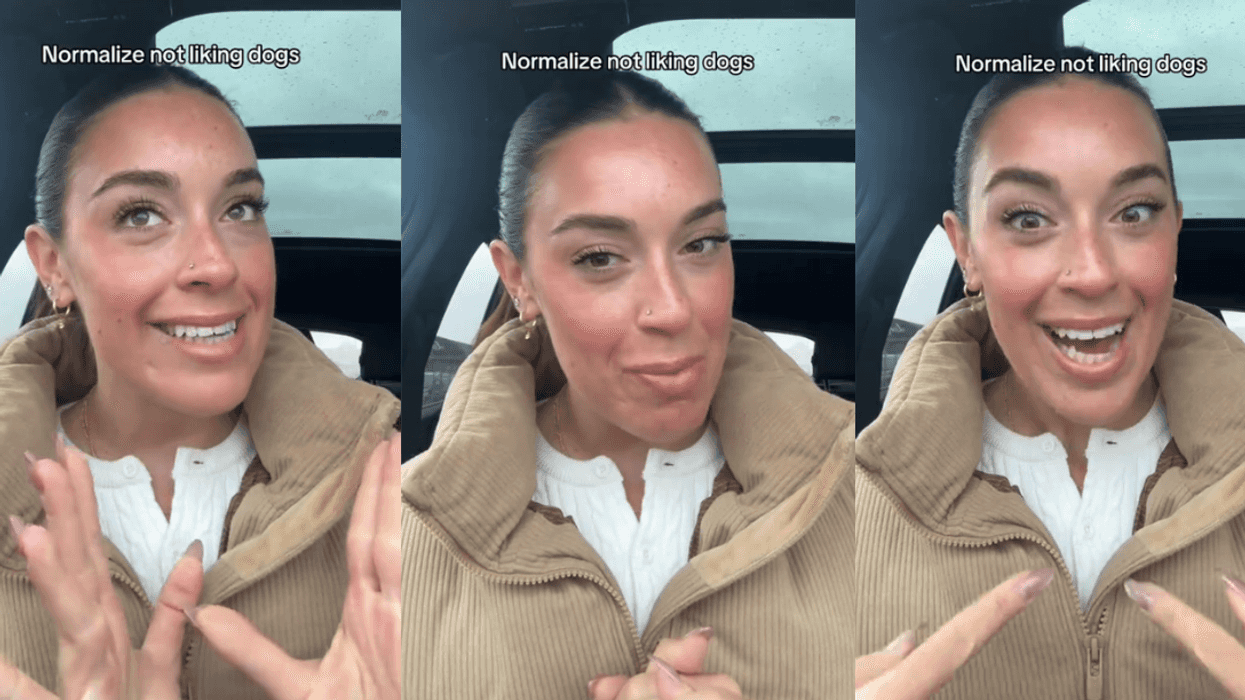

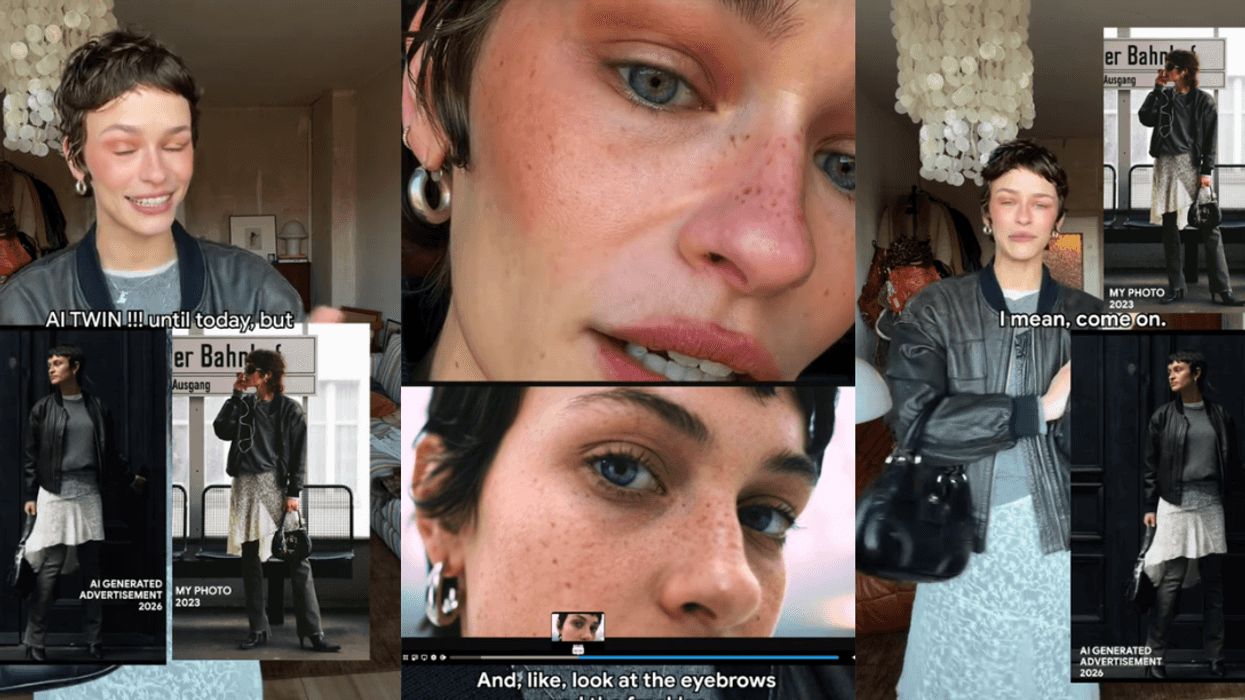

@madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok