One thing is abundantly clear: Mitch McConnell is using the debt ceiling as nothing more than a political gun to hold the Democrats' agenda hostage. He insists, after leading the Republican party to add $7.8 trillion to the debt during the Trump years, that the bill for that largess must be something the Democrats handle alone by raising the debt ceiling.

He knows that the only way Chuck Schumer can raise the debt ceiling is to include it in the massive budget reconciliation bill, and this is a twofer for the GOP: 1) it allows them to label Democrats as the party of debt (not true, but this is politics), and 2) it gums up the budget bill because now it has to bounce between the chambers with a new provision that wasn't in it before.

There have been many proposals on how to get around this, including having President Biden take unilateral action under the 14th Amendment to declare debt ceilings unconstitutional, or even to mint a special $1 trillion coin. But the White House has said, I believe correctly, that this is a problem for Congress as the holder of the nation's purse strings to resolve.

Legal scholars are now beginning to coalesce around an old solution that might have strong political currency today. It's called the Gephardt Rule, named after a popular and effective Congressmember from the last part of the 20th century. When he was a junior member in the House back in 1979, Rep. Dick Gephardt was tasked by Speaker Tip O'Neill with passing the debt ceiling increase, a thankless job that amounted to drumming up votes to actually pay for the programs, people, and military equipment everyone had just ordered. Gephardt figured out a way, however, to rid Congress of the debt ceiling albatross: simply deem the debt ceiling "raised" to account for the budget that was just voted on and passed.

With the blessing of the Parliamentarian, this fix worked like a charm. Whenever the conference report on the budget came out, it would trigger the Rule and the debt ceiling increase was inherently and automatically deemed to have been passed to accommodate the spending and revenues in the budget. But when Republicans took back control of the House in 1995, they saw an opportunity to add political pain back into the process. They suspended the rule so that President Clinton would have to work an extra step to get the ceiling raised. And when the GOP took control of Congress in 2010, they worked to kill the rule and did so officially in 2011 in order to burden the Obama White House.

With the Democrats just barely in control today, it's time to bring the Gephardt Rule back. As Florida State law professor Neil H. Buchanan recently wrote, when the reconciliation bill top-line amount is finally settled upon next month, legislators should simply add the provision, "As appropriate, the Secretary of the Treasury shall compute and is authorized to adjust the borrowing limit to prevent the United States from defaulting on the obligations created under this and previous fiscal measures."

This solution has the added benefit of not putting a dollar limit on the debt ceiling or even actually suspending it. It hands the computations over to the Treasury Secretary and it makes the process no big deal. Professor Buchanan even suggests, for political messaging, that it be called something like the "America Always Pays Its Bills Law."

Other legal experts have begun to weigh in with approval. Professor Laurence Tribe, who reviewed the proposal, called it "a smart way out of the debt ceiling mess" and urged Congress to "include this sentence in the reconciliation measure to call McConnell's bluff." If there are concerns about the timing of the bill, it seems reasonable to assure that this could also be a clean amendment, supported by all 50 Democrats long in advance, that the Democrats promise to add during the Vote-a-Rama process.

McConnell is likely well aware by now that his game of Russian Roulette can be shut down with a reinstatement of the Gephardt Rule. So by insisting that Democrats go it alone on the debt ceiling, he is hoping only to force them to hurry and stress over the big budget bill, which now must come together before a default occurs around October 18. But this pressure might actually play into Schumer's hand by giving him added leverage against the two holdouts in his conference, Sens. Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, whose big corporate backers most certainly do not want to see chaos in the markets.

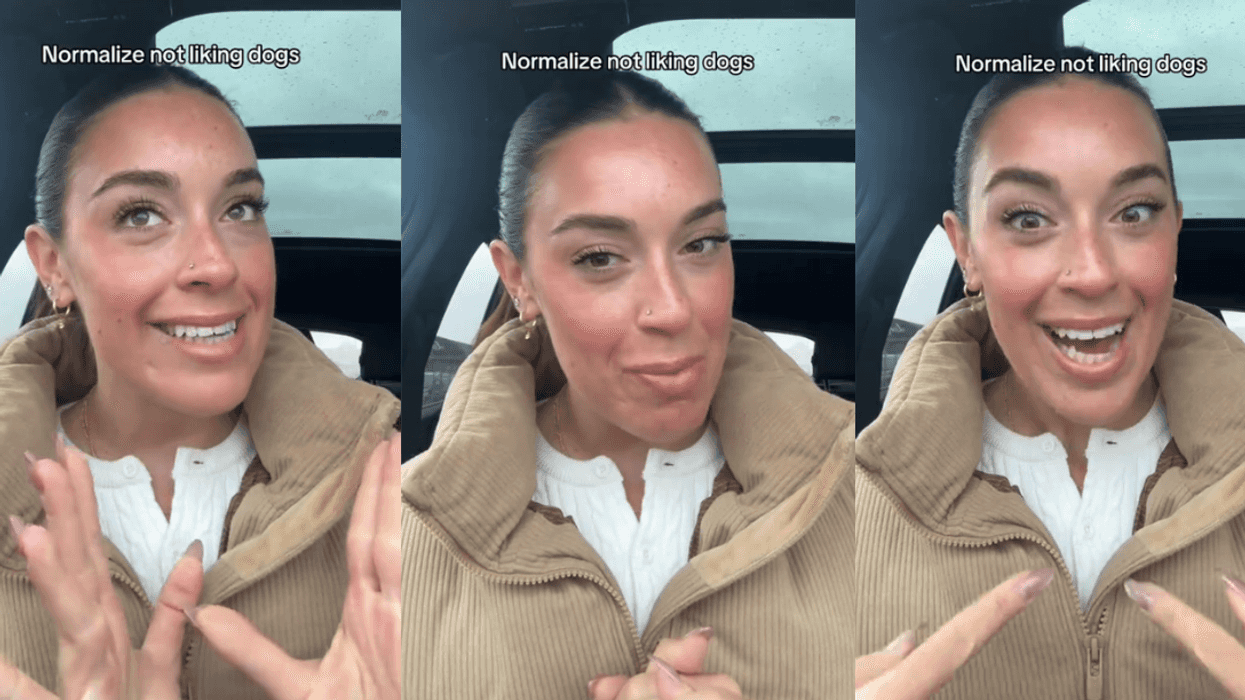

@madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok

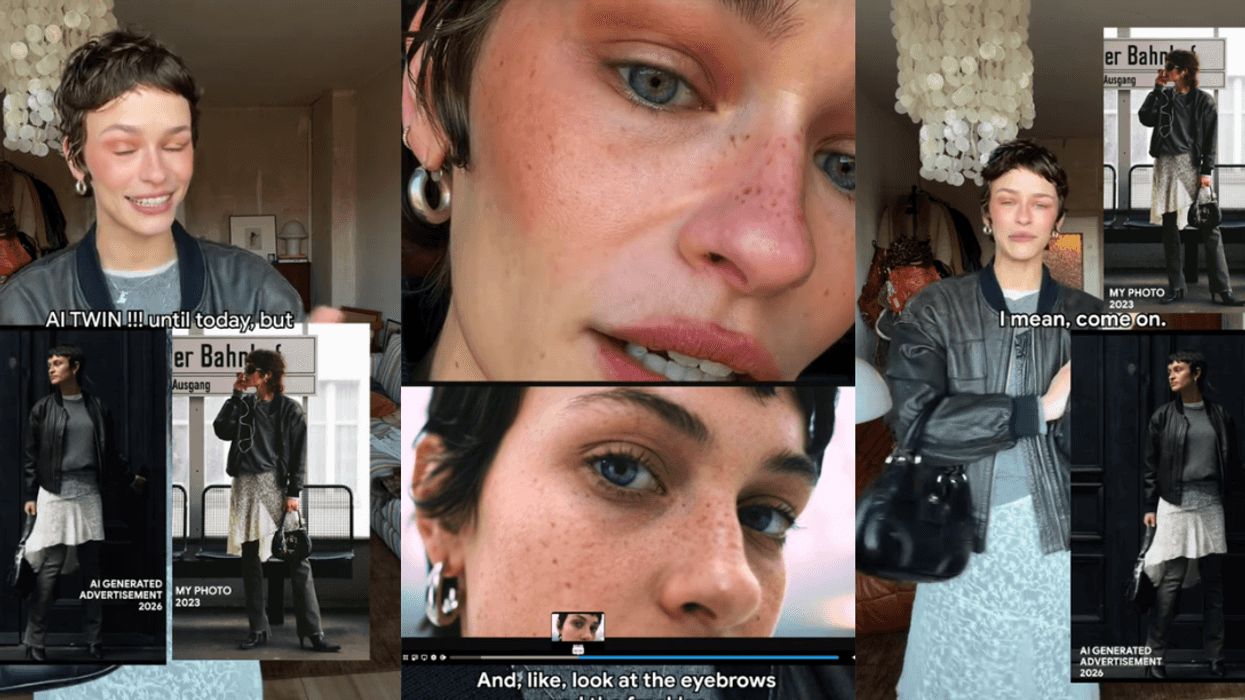

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

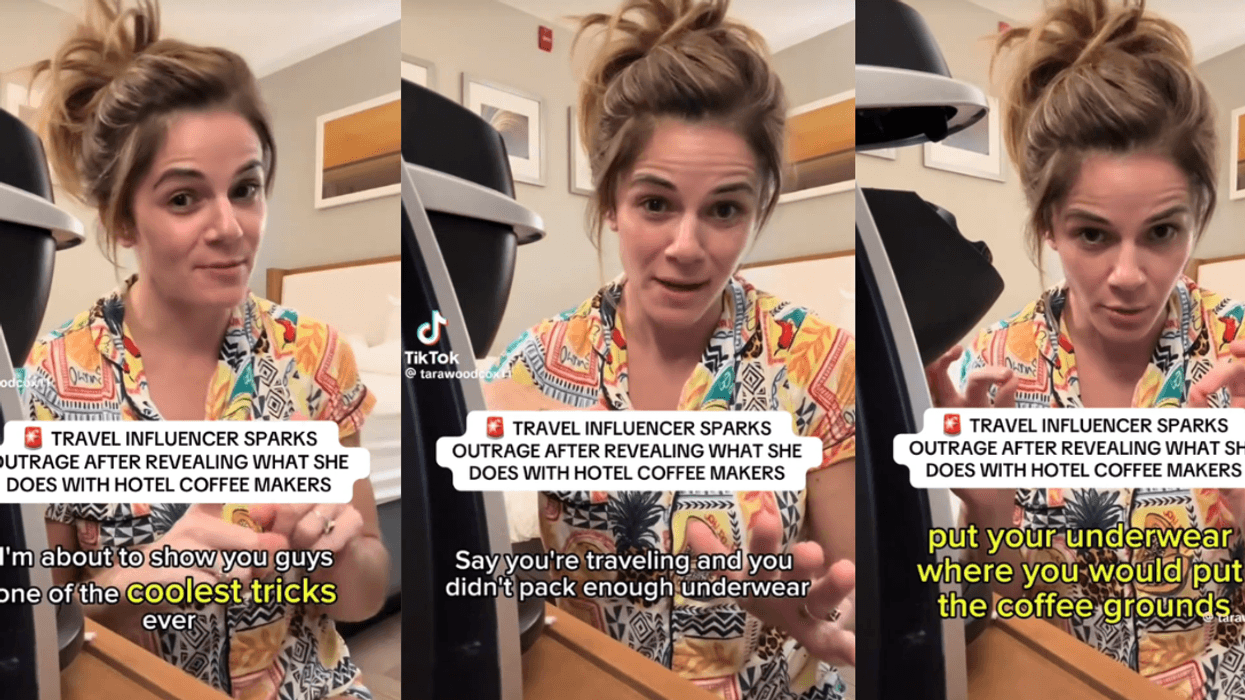

@anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok