If you're a big Monopoly fan you might be getting some extra perks. People who play board games and cards are more likely to stay mentally sharp in later life, according to a new study. Psychologists at the University of Edinburgh tested more than 1,000 people aged 70 for memory, problem solving, thinking speed and general thinking ability.

Those who regularly played non-digital games scored better on memory and thinking tests.

Results also suggested those who increased game-playing during their 70s were more likely to maintain certain thinking skills as they grew older.

“These latest findings add to evidence that being more engaged in activities during the life course might be associated with better thinking skills in later life," Dr. Drew Altschul said. “For those in their 70s or beyond, another message seems to be that playing non-digital games may be a positive behavior in terms of reducing cognitive decline."

So, our skills remain sharp as we get older.

“Even though some people's thinking skills can decline as we get older, this research is further evidence that it doesn't have to be inevitable," Caroline Abrahams, Age UK charity director, said. “The connection between playing board games and other non-digital games later in life and sharper thinking and memory skills adds to what we know about steps we can take to protect our cognitive health, including not drinking excess alcohol, being active and eating a healthy diet."

The participants were part of the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936 study, a group of individuals born that year who took part in the Scottish Mental Survey of 1947.

Results from an intelligence test they sat when they were 11 years old were also taken into account, with the new results having repeated the same thinking tests every three years until aged 79.

As well as considering lifestyle factors, such as education, socioeconomic status and activity levels, Professor Ian Deary suggested it would be beneficial to test which types of games work better than others.

“We and others are narrowing down the sorts of activities that might help to keep people sharp in older age," the director of the University Centre for Cognitive Aging and Cognitive Epidemiology (CCACE) said. “In our Lothian sample, it's not just general intellectual and social activity, it seems – it is something in this group of games that has this small but detectable association with better cognitive aging. It'd be good to find out if some of these games are more potent than others. We also point out that several other things are related to better cognitive ageing, such as being physically fit and not smoking."

The study is published in The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences.

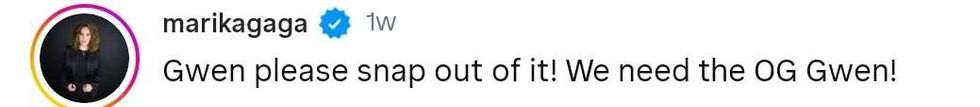

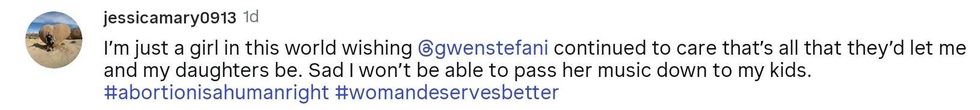

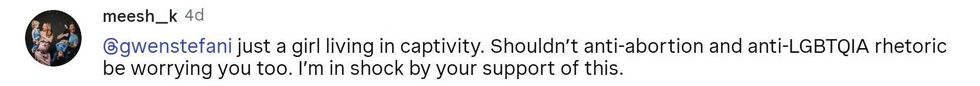

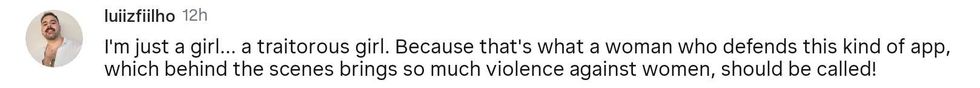

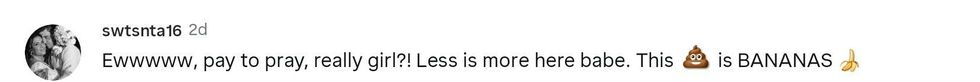

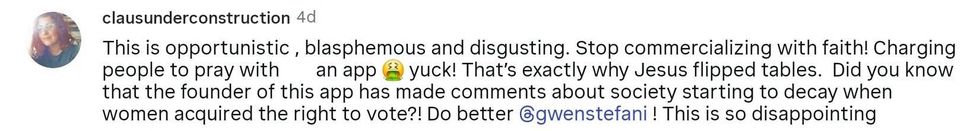

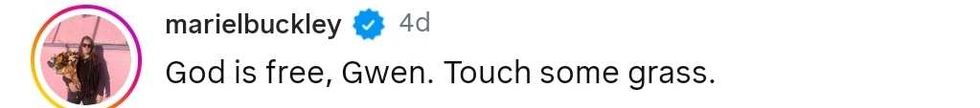

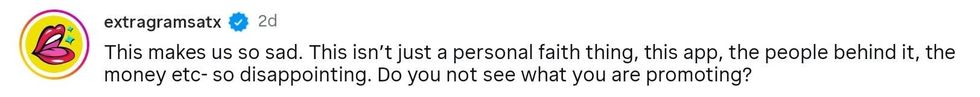

@gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram @gwenstefani/Instagram

@gwenstefani/Instagram