Brett Kavanaugh, President Donald Trump's next nominee for the U.S. Supreme Court, thanked the president during a speech last night. The moment would have gone over well enough had it not been for a strange claim he made about the president's selection process.

“No president has ever consulted more widely, or talked with more people from more backgrounds, to seek input about a Supreme Court nomination,” Kavanaugh said.

That comment does not hold up to scrutiny, notes analyst Aaron Blake, who in a piece for The Washington Post explains just why Kavanaugh's claim is so dubious:

It may seem like a throwaway line — a bit of harmless political hyperbole. But this was also the first public claim from a potential Supreme Court justice who will be tasked with interpreting and parsing the law down to the letter. Specificity and precision are the name of the game in Kavanaugh's chosen profession. How on earth could he be so sure?

There have been 162 nominations to the Supreme Court, according to U.S. Senate records, over the past 229 years. (The Supreme Court began in 1789.) For Kavanaugh to make such a claim, he would have to have studied not just those confirmations, but the often-secretive selection processes that preceded them. These things, quite simply, are not a matter of public record or even all that well documented by reporters. A week ago, for example, most media outlets were reporting the list of three finalists did not include Thomas Hardiman. By the end, it was believed Kavanaugh's top competitor was Hardiman.

Besides, Blake notes, it is "basically impossible to know" everyone who may have been on President George W. Bush's short list (for multiple reasons) so it makes little sense that Kavanaugh would say what he did when precision with language is the name of the game for a Supreme Court justice, potential or otherwise:

It is basically impossible to know everybody with whom George W. Bush consulted on his Supreme Court nominations, much less George Washington. There may be some justification for Kavanaugh's comment based upon the increasing diversity of American politics and society more generally, but it is a completely unprovable assertion — and one that would require a basically unheard-of level of research to substantiate.

Beyond that, there are reasons to doubt it. Trump actually leaned quite heavily on a list of names he did not put together himself but were instead provided by the conservative Federalist Society — a group whose ideological diversity is not exactly vast. Trump did not stray from that list for either this selection or Neil M. Gorsuch's. And Trump spent a relatively brief two-week period making this decision. Barack Obama, by contrast, spent about a month reviewing his options before he nominated Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

Social media tore into Kavanaugh as well...

...with analyst Seth Abramson calling for the Senate to demand that Kavanaugh's "secret list of replacement jurists" be made public.

Others drew parallels between Kavanaugh's comments and those made by physician Ronny Jackson, whom the president nominated to be United States Secretary of Veterans Affairs to succeed David Shulkin. Many raised questions about Jackson's experience and qualifications, particularly after it emerged that the president nominated Jackson because he liked the way Jackson handled himself in January when speaking to reporters during an extended grilling about Trump’s health and cognitive fitness. (At the time, Jackson claimed Trump's neurological functions are excellent and assured the press corps that he would be able to finish out his term. He added that Trump likely had “incredible genes” that allowed him to remain healthy despite a lack of exercise and a taste for fast food.)

Kavanaugh's nomination has not come without controversy.

Although the president had not until earlier yesterday released a public shortlist, Kavanaugh was believed to be under consideration along with Raymond Kethledge, Amy Coney Barrett, and Thomas Hardiman as a top contender to replace Justice Anthony Kennedy, whose sudden announcement that he would retire from the Supreme Court raised fears that abortion rights (Roe v. Wade) and marriage equality (Obergefell v. Hodges) would be on the chopping block.

Nevertheless, Kennedy’s announcement was lauded by many conservatives who view the Supreme Court opening as an opportunity for President Donald Trump to codify his legislative agenda. Liberal opponents have opposed the nomination, citing a precedent set by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), who infamously refused to hold hearings for Merrick Garland, President Barack Obama’s nomination for the high court. At the time, McConnell claimed that the Senate should not confirm Supreme Court nominees during an election year, though he could cite no rules to support this assertion, and accusations that his decision was informed, at least in part, by racial animus toward Obama have dogged him ever since.

Others have expressed outrage at the notion that a president under federal investigation could nominate someone with the potential to sway the court’s opinion in the event of an indictment.

To that end, it’s obvious why the president ultimately picked Kavanaugh, who is perhaps best known for the leading role he played in drafting the Starr report, which advocated for the impeachment of President Bill Clinton and whose views about when to impeach a president are likely to become contentious subjects during his Senate confirmation hearing.

Kavanaugh, for his part, has since expressed misgivings about the Starr report; in 2009, he wrote that Clinton should have been spared the investigation, saying that indicting a sitting president “would ill serve the public interest, especially in times of financial or national-security crisis.” Writing in the Minnesota Law Review, he suggested that Congress should pass laws that would protect a president from civil and criminal lawsuits until they leave office. He added that there was always a way to remove a “bad-behaving or lawbreaking President.”

“If the president does something dastardly,” he wrote, “the impeachment process is available.”

Several senators, including Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Chuck Schumer (D-NY) have announced they intend to oppose Kavanaugh's nomination.

The president, for his part, has gloated about the "GREAT" reviews Kavanaugh has received.

Regardless "of whether this will cost Kavanaugh, it is a thoroughly inauspicious way to begin your application to the nation's highest court, where you will be deciding the merits of the country's most important legal and factual claims," observes Aaron Blake, who, like many of us, is curious about what the Senate confirmation process––sure to be grueling––will bring to an already contentious nomination.

@catmeo28/TikTok

@catmeo28/TikTok @kelcag89/TikTok

@kelcag89/TikTok @andrew_gilstrap/TikTok

@andrew_gilstrap/TikTok @briezeus/TikTok

@briezeus/TikTok @dexx_uppercutt/TikTok

@dexx_uppercutt/TikTok @whoozqueen/TikTok

@whoozqueen/TikTok @greg_clubsandwich/TikTok

@greg_clubsandwich/TikTok @amieeetaylor/TikTok

@amieeetaylor/TikTok @lexyylee/TikTok

@lexyylee/TikTok @johnnnnnnm6/TikTok

@johnnnnnnm6/TikTok @essencechone/TikTok

@essencechone/TikTok @aksewgnarly/TikTok

@aksewgnarly/TikTok

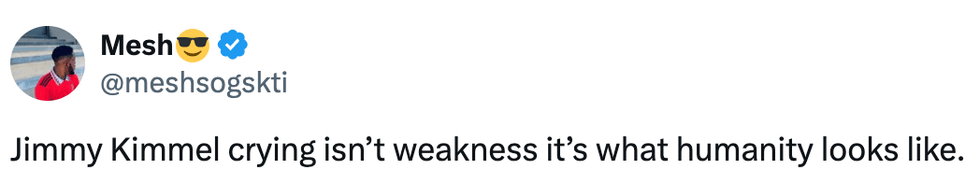

@meshsogskti/X

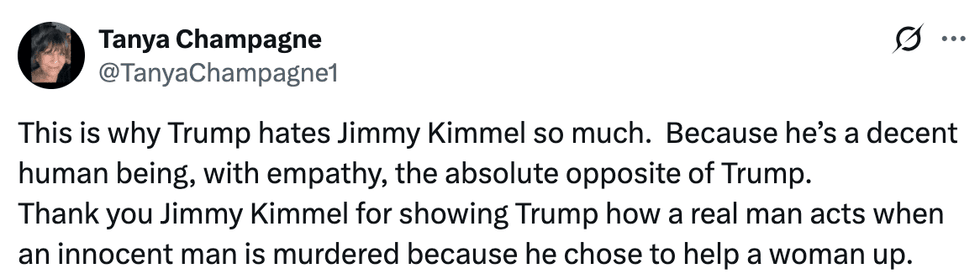

@meshsogskti/X @TanyaChampagne1/X

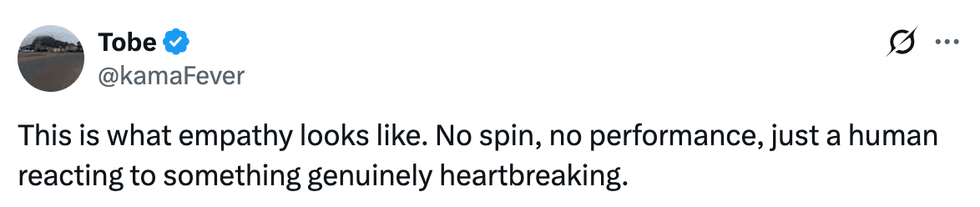

@TanyaChampagne1/X @kamaFever/X

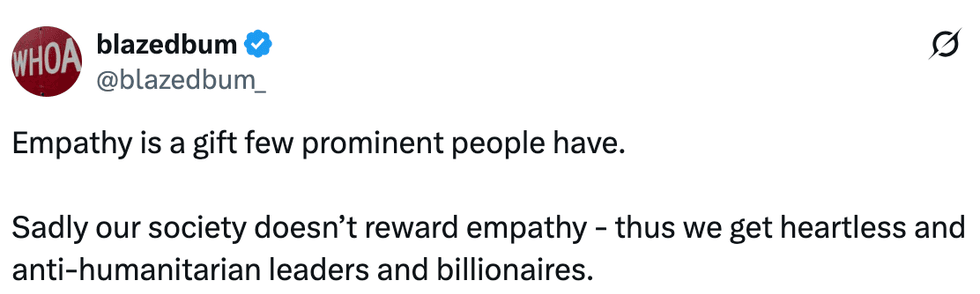

@kamaFever/X @blazedbum_/X

@blazedbum_/X

@bbcradio1/TikTok

@bbcradio1/TikTok @bbcradio1/TikTok

@bbcradio1/TikTok @bbcradio1/TikTok

@bbcradio1/TikTok @bbcradio1/TikTok

@bbcradio1/TikTok @bbcradio1/TikTok

@bbcradio1/TikTok @bbcradio1/TikTok

@bbcradio1/TikTok @bbcradio1/TikTok

@bbcradio1/TikTok @bbcradio1/TikTok

@bbcradio1/TikTok @bbcradio1/TikTok

@bbcradio1/TikTok @bbcradio1/TikTok

@bbcradio1/TikTok @bbcradio1/TikTok

@bbcradio1/TikTok @bbcradio1/TikTok

@bbcradio1/TikTok @bbcradio1/TikTok

@bbcradio1/TikTok @bbcradio1/TikTok

@bbcradio1/TikTok @bbcradio1/TikTok

@bbcradio1/TikTok