Can’t resist that juicy, ripe summer raspberry? It turns out your appetite may not be driving the show — the raspberry plant likely knows exactly what it’s doing.

Almost all fruits have seeds, and they’re designed that way for reproductive purposes; animals eat the fruit, transport the seeds internally, and — eventually — deposit them far and wide, ensuring the continuation of the plant species.

Scientists have long assumed fruits were so attractive to animals due to simple natural selection — the juiciest, most delicious fruits get the most takers. However, two recent studies have indicated that plants themselves could actively be adapting to specific animals’ sense of sight and smell.

One of the reports, published in late September in Biology Letters, compared the evolution of fruit color on plants in a national park in Madagascar, where the primary animals for seed dispersal are red-green colorblind lemurs, and one in Uganda, where the seed dispersers are typically primates and birds with normal vision.

The fruits in Uganda were found to have higher contrast against the leaves in the background in the “red-green and luminance channels,” where the yellow-blue channel was favored in Madagascar — specifically, the scientists believed, to mitigate the visual limitations of the night-hunting lemurs.

“When I first learned that plants, in a way, behaved — that they were actually communicating information to animals — my mind exploded,” Kim Valenta, evolutionary ecologist at Duke University and co-author of the study, told The New York Times. “We’re only just beginning to understand how much plants and animals mean to one another, which to me is just a signal that it’s more important to conserve the entire [ecosystem] intact.”

The second study, published in early October in Science Advances, showed that plants that rely on night-hunting colorblind lemurs for seed dispersal actually created more fragrant fruits to overcome the lemurs’ sight disability.

In the past, scientists had assumed fruit with a strong scent was simply an unintended result of chemicals released during the ripening process — not an intentional adaptation to attract seed-dispersing animals.

The Science Advances study, however, showed that fruits that relied primarily on birds for seed dispersal were significantly less scented when ripe.

“The idea was that birds have presumably a lower reliance on their sense of smell and they have really, really good color vision, so they tend to focus on visual cues like food color,” Omer Nevo, evolutionary ecologist at Germany’s Ulm University, one of the study authors, and a colleague of Dr. Valenta’s, told NPR. “And then the expectation is that in these fruits, you would see less pressure on the plants to signal ripeness through the scent of the fruit…. And that’s exactly what we found.”

Nevo and his team discovered that, indeed, for the bird-focused fruit, there was little scent difference between the ripe and unripe versions — indicating that the plants were actively adapting their fruits for their primary seed-dispersal candidates.

"This showed us that this change in the amount and in the chemical that is emitted by fruit in the lemur-dispersed species is not an inevitable byproduct of the fruit-ripening process, it's not something that characterizes all fruits but something that is unique to fruit for whom it would be useful," Nevo said. "Because the animals use the scent."

Summary: Two new studies find that plants can change the color and scent of their fruit to appeal to the animal(s) most likely to eat it and disperse its seeds.

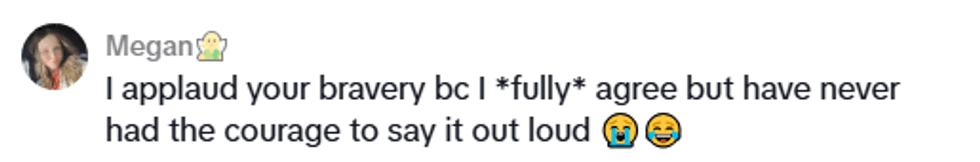

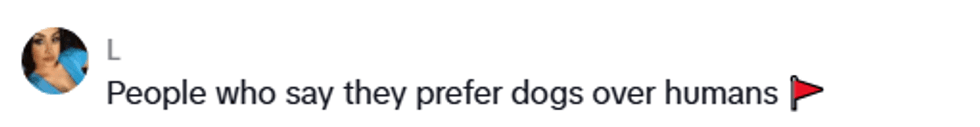

@madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok

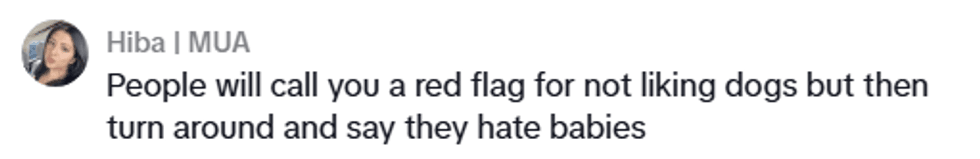

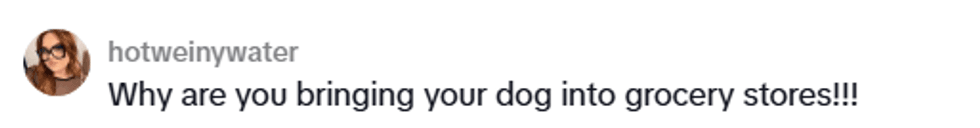

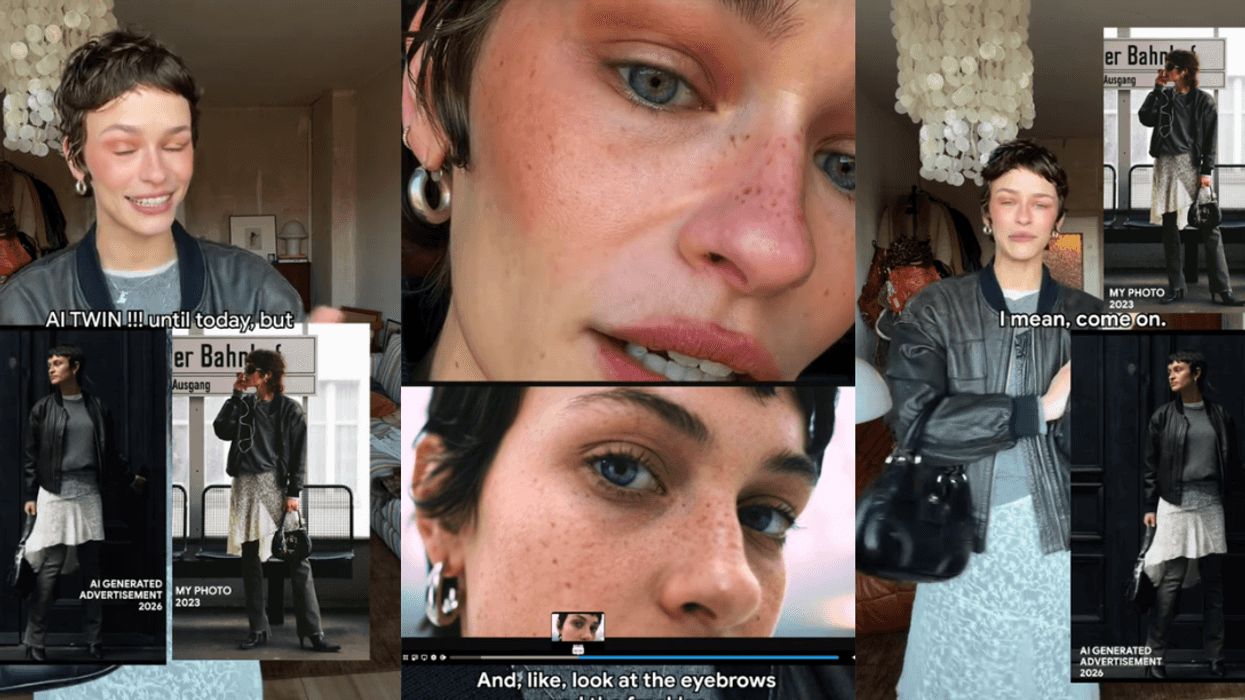

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

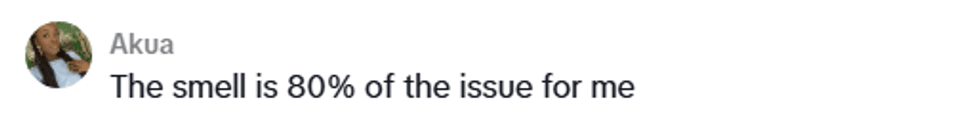

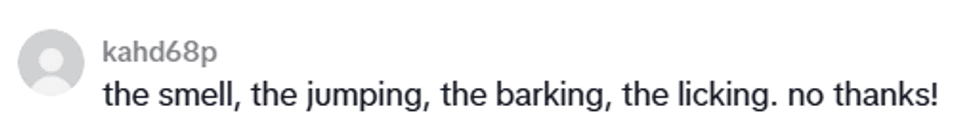

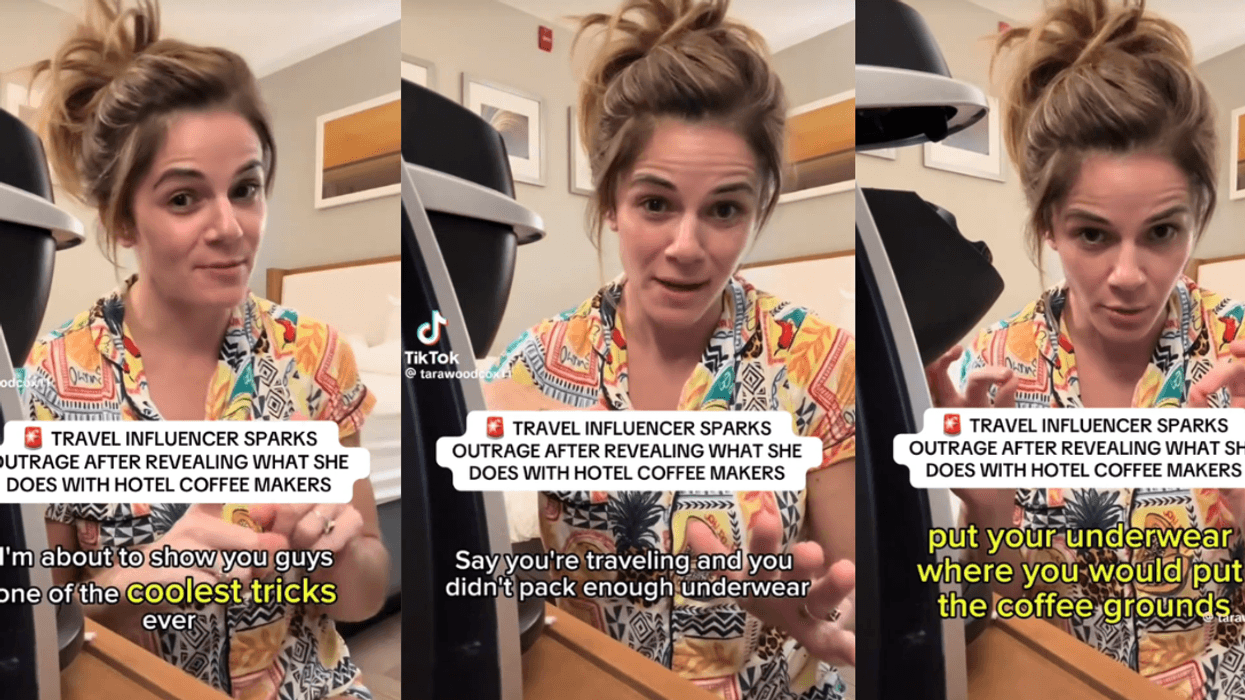

@anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

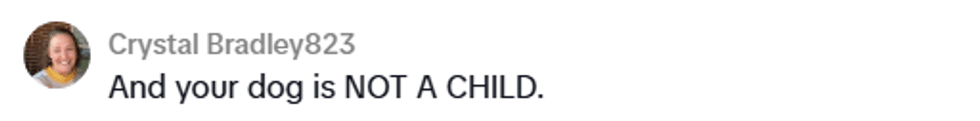

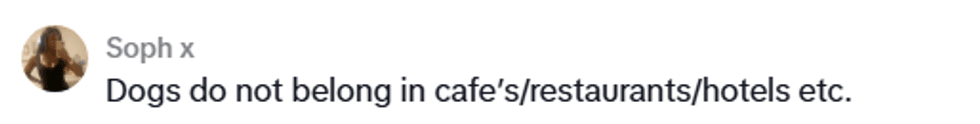

@hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok