Every other day, there seems to be new bad news about climate change. Polar bears are struggling to survive. The Arctic is warming even faster than expected. Millions of people may soon be without usable land, leaving them subject to famine and drought. But mixed among these headlines in recent weeks, there was a glimmer of hope, from an unexpected source: China.

China has long been known for dangerous levels of air pollution. Images of the biggest cities often show buildings cloaked in dense smog and people wearing masks to protect themselves from the particulates. It is estimated that more than 1.5 million people die from air pollution-related causes in China each year.

In 2013, the government began implementing strict rules to get the problem under control. The plan has so far focused on reducing the production of steel and the use of coal for electricity. And so far, it seems to be working.

Michael Greenstone, an economics professor and head of the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago, wanted to see for himself just how the reduction in air pollutants might affect individual Chinese citizens. He gathered data from nearly 250 air quality monitors maintained by the government and found that some of the most populated areas had seen some of the biggest improvements, and their residents seemed to benefit.

In Beijing, the concentration of fine particulates, which can cause everything from eye and throat irritation to asthma and heart disease, had declined by 35 percent since 2013. In Shijiazhuang, the capital city of Hebei province, particulates dropped by 39 percent, and in Baoding, which gained the moniker of China's most polluted city in 2015, pollution declined by 38 percent.

The result, according to Greenstone’s calculations: If this trend continues, Chinese residents can expect to live 2.4 years longer on average. In Beijing, residents gain closer to 3.3 years, in Baoding it's 4.5 years, and in Shijiazhuang he predicts a whopping 5.3 more years of life on average, for people of all ages.

Greenstone contrasts this speedy result with the impact of the Clean Air Act of 1970 in the United States, which took about a dozen years to achieve about the same amount of air particulate reduction that China pulled off in just four. But in exchange for those potential extra years of life, Chinese citizens have had to deal with significant restrictions, as well as lost income as steel and coal jobs disappear. China achieved its air pollution success thus far through an “engineering-style fiat that dictates specific actions, rather than relying on markets to find the least expensive methods to reduce pollution,” Greenstone said.

This strategy likely won't work in many other places, especially the United States.

And the fact remains that China's air is still extremely polluted. Particulate levels have yet to reach the country's own safety standards, let alone those of the World Health Organization. But Chinese officials say they have only begun their anti-pollution efforts. Earlier this year, environment minister Li Ganjie said the country is implementing stricter targets for reducing smog by 2020.

But in a world that constantly feels on the brink of climate catastrophe, results like this are encouraging to many. That includes the president of South Korea, Moon Jae-in, who recently said he planned to work with China to tackle air pollution in both countries.

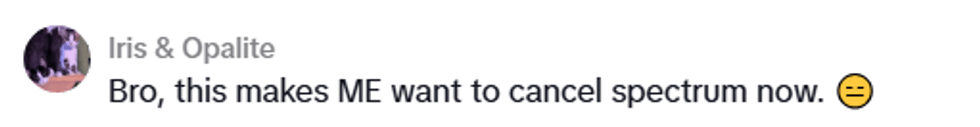

@madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok

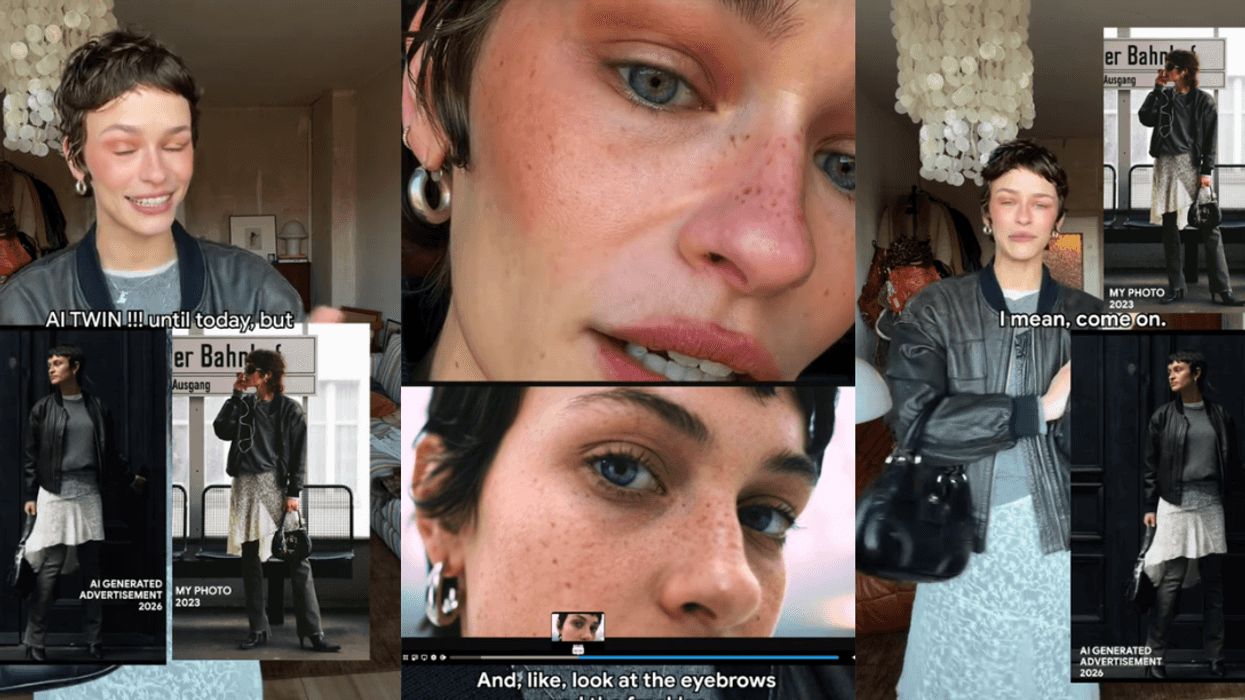

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok