When you responsibly toss that water bottle into a recycling bin, you assume that it will be somehow recycled—maybe reborn as a park bench, a fleece jacket, or another water bottle. That reuse cycle was made possible largely due to China. For more than 25 years, recycled bottles and other plastic waste from the West were shipped to China, where they were sorted, cleaned, and turned into plastic pellets, which could be melted and turned into new products. Since 1992, about 45 percent of the world’s plastics sorted for recycling were sent to China—about 106 million metric tons of the stuff, which increased in volume by 800 percent until 2016, when China was receiving about two-thirds of the world’s plastic trash. Up until 2018, China accepted garbage from 43 countries. And then China got sick of taking in our garbage.

In January of 2018, China banned the import of plastic waste. The National Sword policy was created to protect China’s environment. Air and water quality in many parts of the nation have been devastated, first by the initial production of plastics, a petroleum product, and next by the return of all that garbage, much of which couldn’t actually be recycled after all due to contamination issues. The new policy bans 24 types of solid waste, including various plastics and unsorted mixed papers. Many trash exporting countries, including the U.S., Canada, and Australia, objected to the plan, as they now have to be responsible for their own garbage. So what happens now?

Some countries, like Britain, have no system for dealing with recycled material. Previously, it was all sent to China. Now it’s being sent to landfills in other countries. In states like Kansas, plastics are just stacking up, with nowhere to go. In other places, new recycling guidelines are being devised to let consumers know upfront that some materials can no longer be recycled, as markets don’t exist for those materials.

“This is not a little disruption,” says Susan Collins, president of the Container Recycling Institute, a research organization based in Southern California. “This is a big disruption to a bigger industry than most people would think it is, because it’s sort of an invisible process. You put your stuff out at the curb, and it goes away — nobody thinks about it as being a multibillion industry in this country.”

A few other nations have been willing to become the new dumping ground for the world’s plastic trash. Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, Turkey, and Poland have accepted some trash imports, but quickly became overwhelmed, and introduced bans and limits on the volume.

Americans generate such extreme amounts of trash that no domestic system exists that can handle the volume. The country depends on developing countries to pick up its trash. That becomes a big problem for the receiving countries. When several African countries moved to ban imports of Americans’ used and unwanted clothing, the Trump administration threatened to punish them with tariffs. The imported used clothing—typically unsold stock from U.S. thrift stores—is often inappropriate for the climate or culture in Africa, and has stifled the development of an African textile industry, which in decades past was a vibrant part of many African countries’ agriculture, manufacturing economy, and culture.

China’s move makes it clear that the countries that produce massive amounts of garbage must begin to take responsibility for dealing with it—and it’s an issue of monumental proportions. Single-use plastics such as plastic bags are used for an average of 12 minutes, yet continue to exist in the environment for hundreds of years or more. Even when plastic breaks down, those tiny particles, called microplastics, enter the food cycle and wreak havoc on wildlife. Scientists estimate that by 2050, there will be more plastic than fish in the ocean. Up to 12 million metric tons of plastic trash ends up in the the oceans every year. That amount is expected to triple within the decade.

While many consumers feel they are taking responsibility for their own waste simply by recycling, the reality is that only about 14 percent of the plastic packaging waste is even collected for recycling, and of that, Chinese and other recyclers could only recycle a portion of the collected material, due to contamination by food waste or non-recyclable material mixed in by accident or through “wish-cycling”—when consumers hope that non-recyclable material will somehow be recycled if it’s included in the recycled waste stream. So instead, huge amounts of plastic and other recyclable material ends up being incinerated or landfilled.

"Not one country alone has the capacity to take what China was taking," says Jenna Jambeck, author of a study on the impact of China’s plastics ban. "What we need to do is take responsibility in making sure that waste is managed in a way that is responsible, wherever that waste goes — responsible meaning both environmentally and socially."

As waste management companies scramble for a solution, the most responsible thing consumers can do is vote with their wallet and refuse to buy plastic-packaged products in the first place. The Zero Waste movement encourages consumers to buy in bulk, buy secondhand, or decline to reward companies that use excessive plastic packaging. That can be an extreme challenge for most people, however. Food producers in particular have embraced plastic in recent years, and products that were once packaged in paper, glass, cardboard or metal are now available only in plastic. Foods like Pop-Tarts, Popsicles, chocolate bars, and milk have switched from paper wrappers or cartons to plastic. New plastic packaging, such as pouch food with large plastic sucking devices have entered the market. Grocery store samples are served with tiny plastic utensils and cups that are used for mere seconds. Cardboard milk cartons now have plastic spouts. It is nearly impossible to escape plastic at the grocery store.

Consumer pressure has led some companies to reconsider their role in producing plastic garbage. Starbucks recently introduced a straw-free cup design. More restaurants are switching to an “opt-in” policy for straws; instead of automatically providing them. Some stores are charging for plastic bags to encourage consumers to bring reusable bags. However, the corporations that produce plastic packaging have lobbied hard on behalf of their industry; posing the matter as a “customer choice” issue, plastic producers have successfully lobbied for laws that prevent states from enacting bag bans or other legislation that would regulate plastic trash.

This has led some consumers to understand that their behavior is not the problem, so much as that of the corporations that make decisions to use plastic in the first place. In the UK, grocery shoppers are staging “plastic attacks” on grocery stores. To show their displeasure about the lack of sustainable choices, they are unwrapping their purchases and returning the non-recyclable plastics at the stores. The Plastic Attack movement has since gone global, staging protests and cleanup events.

"We decided it was time to show supermarkets just how many shoppers were concerned about the amount of plastic packaging on their food," explained Alex Morss, who helped organize some of the first events. "We're not a bunch of anarchists," says Morss. "We're very polite, well-mannered people of all ages, from teens to people in their 80s and 90s."

For years, China has insulated western economies from the impact of their consumption. Now wealthier countries are forced to face their own garbage, and the mountain of trash just keeps getting higher.

@madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok @madswellness/TikTok

@madswellness/TikTok

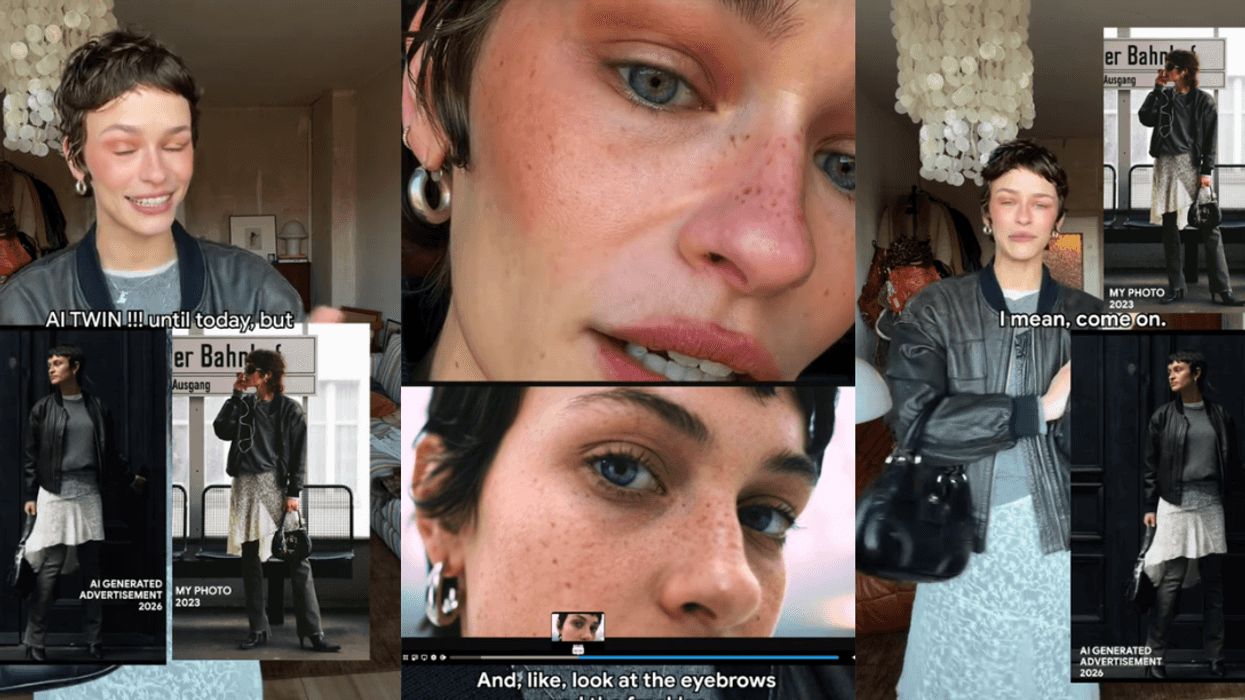

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok @vanellimelli030/TikTok

@vanellimelli030/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok @anissahm15/TikTok

@anissahm15/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok @hustleb***h/TikTok

@hustleb***h/TikTok