Democrats and voting rights advocates cheered the news on Monday that the Justice Department has now waded in to help stop extreme gerrymandering, suing Texas for its highly suspect maps that on their face appear to perpetuate white minority rule. “The Justice Department will not stand idly by in the face of unlawful attempts to redistricting access to the ballot,” said Associate Attorney General Vanita Gupta, who also noted that Texas rammed through the new maps in less than three months in a rushed legislative process that nearly shut out all public input.

So how bad is the new Texas map? Consider this: Whites now comprise less than 40 percent of the state’s population but they control 60 percent of the districts. Hispanics are 39 percent of the population but control only 18 percent of the seats, while Blacks are 12 percent but control none of the seats.

Moreover, Texas grew by nearly 4 million people from 2010 to 2020 according to the census, granting the state two more seats in Congress. An astonishing 95 percent of that growth came from new minority residents. But the new maps don’t reflect that at all. Instead, they were designed to give the two new districts Anglo voting majorities while eliminating Latino electoral opportunities in West Texas, failing to draw a seat encompassing Latino-heavy Harris County, and surgically excised minorities communities from the Dallas-Forth Worth metroplex by attaching them to heavily Anglo counties more than 100 miles away in a process known as “cracking.”

If this feels to you like it ought to be facially illegal, you have some historical support. Texas’s maps have been held in violation of the Voting Rights Act in every single decade since the Act became law. The difference today is that the Supreme Court, through a series of blows to the Act, has made it very hard to stop the process before elections happen and has raised the bar nearly impossibly high for what comprises a violation.

At the risk of oversimplification, it used to be the case that any redistricting map put out by Texas, which has had a long history of diluting the voting power of its minority residents, would have to go through “preclearance” by the Justice Department or a panel of federal judges before it could go into effect. At the last round of gerrymandered redistricting back in 2011, the proposed maps were rejected by the Department, and a federal judge found that the maps had been drawn with racially discriminatory intent.

Then three things happened to dangerously erode protections against voter suppression and specifically against gerrymandering. First, the Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder rolled back the “preclearance requirement” of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, saying essentially that the Section was penalizing jurisdictions unfairly for problems that had long been resolved. The Court then instructed Congress to come up with new criteria. (The Republican-controlled Congress, unsurprisingly, failed to act.) That ruling lifted safeguards that had kept more aggressive voter suppression laws and extreme gerrymandering in check. Justice Ginsberg in a famous dissent wrote, “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

Second, the Court held in Rucho v. Common Cause that partisan gerrymandering, i.e. drawing maps specifically to disadvantage one party or the other, was a political question that lay beyond the power of the federal courts to resolve. This ruling further opened the door for legislatures to create extremely partisan maps so long as they could argue they were not racially discriminatory.

Then in Abbott v. Perez, the Supreme Court, in upholding the new Texas maps, reversed the lower court’s findings that racial discrimination had infected the map-drawing process. It set out a new standard for federal courts to put jurisdictions back under preclearance for violations, requiring courts from here out to presume the good faith of the legislature in drawing maps. This ruling helps explain why new maps are drawn hastily and without much public commentary time, obfuscating the process and making it hard for plaintiffs to prove discriminatory intent. As Loyola professor Justin Levitt stated when the decision was announced, “What any other state can take from today’s decision is, ‘If I intend to discriminate, a court may nip and tuck a bit, but they’re not going to undo what I’ve done wholesale.’”

This is a long way to point out that there are severe challenges and roadblocks, intentionally laid in place by a conservative majority on the Supreme Court, that gut the protections of the Voting Rights Act. Without a new law to restore preclearance (something the stalled Freedom to Vote Act would do, but for the filibuster that prevents its passage), there is only a low chance that a Justice Department lawsuit ultimately would succeed under this far narrower legal rubric—and an even lower chance that the case would be decided in time for the 2022 midterms or even the 2024 election.

The only solace is that, at least as things stand, in order to preserve their Congressional incumbencies the GOP has had to cede more “safe” seats to the Democrats but continues to enjoy an outsized advantage from packing its opponents so heavily together while cracking minority heavy blue districts and attaching them to Anglo-heavy red ones. That leaves only three districts with competitive races (< 10% margin) in the entire state, at least for now.

But eventually, likely sometime mid-decade, the math will catch up to the Republicans as the state continues tipping more blue and population growth continues to draw primarily from minority communities. This is a fight the Texas GOP, like the once-mighty California GOP, ultimately will lose. The question then is, if conservative Democrats won’t eliminate the filibuster to protect voting rights, how much damage will Texas’s and others states’ gerrymandering do in the meantime?

For more political analysis, check out the Status Kuo newsletter.

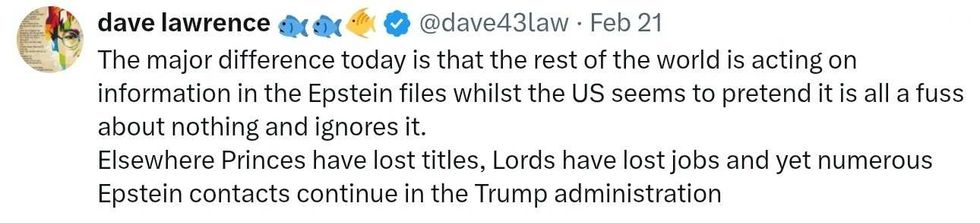

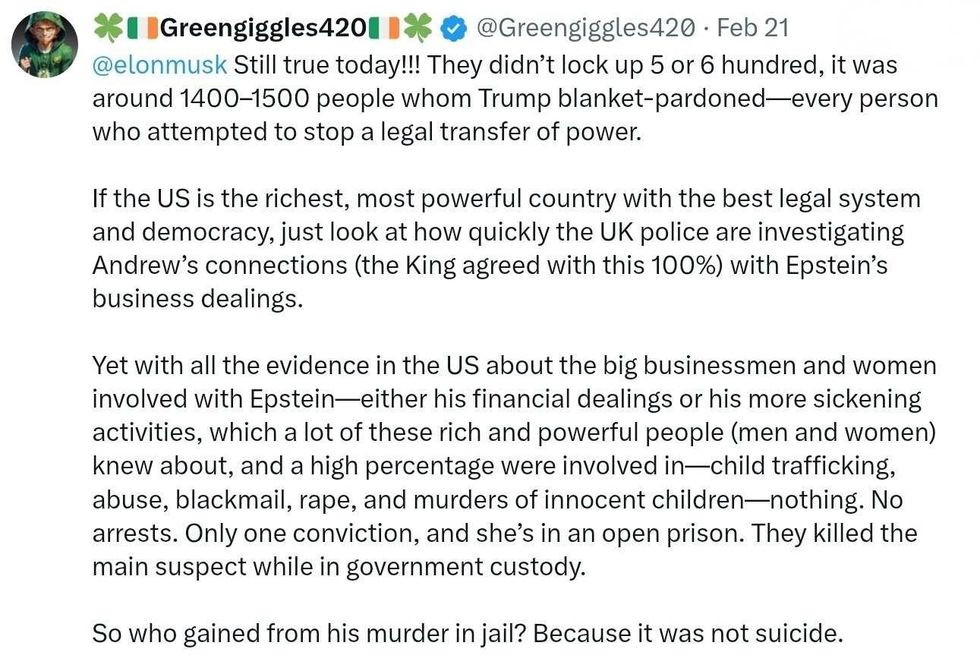

reply to @elonmusk/X

reply to @elonmusk/X reply to @elonmusk/X

reply to @elonmusk/X reply to @elonmusk/X

reply to @elonmusk/X reply to @elonmusk/X

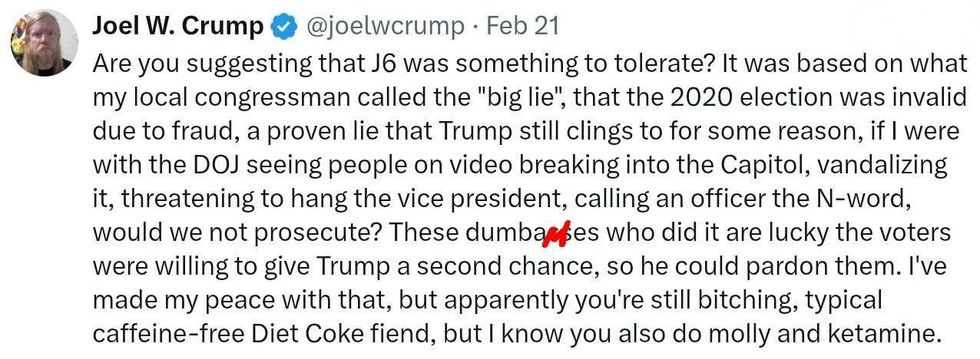

reply to @elonmusk/X reply to @elonmusk/X

reply to @elonmusk/X reply to @elonmusk/X

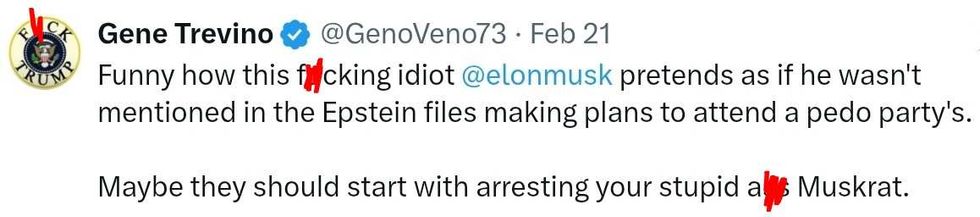

reply to @elonmusk/X reply to @elonmusk/X

reply to @elonmusk/X

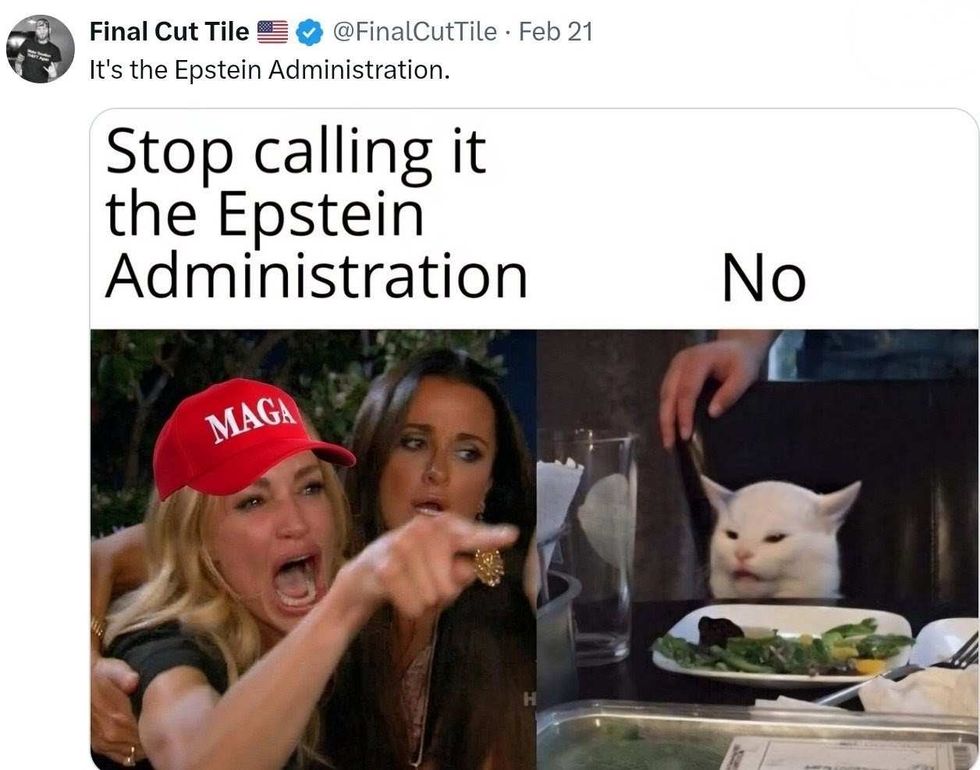

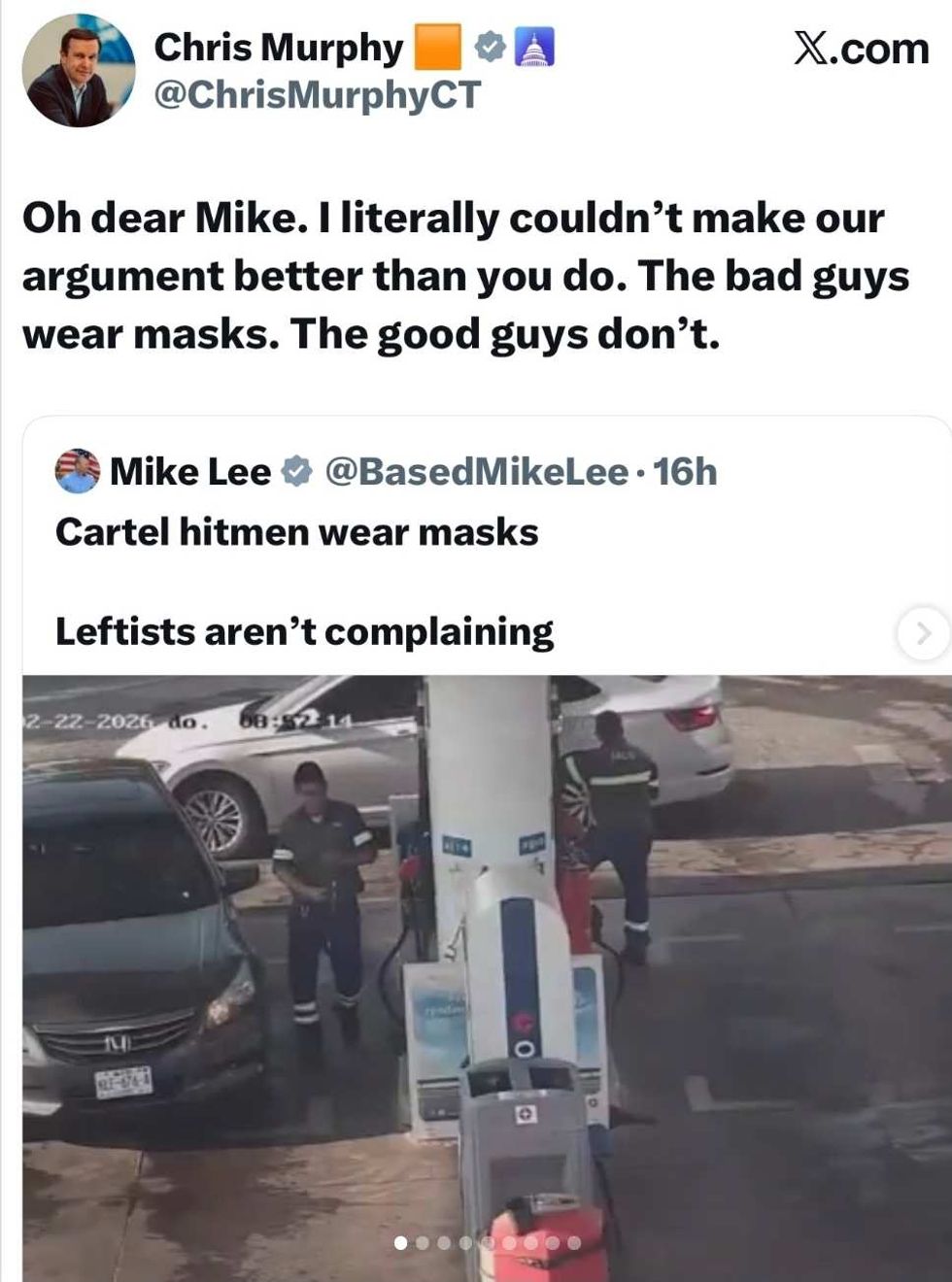

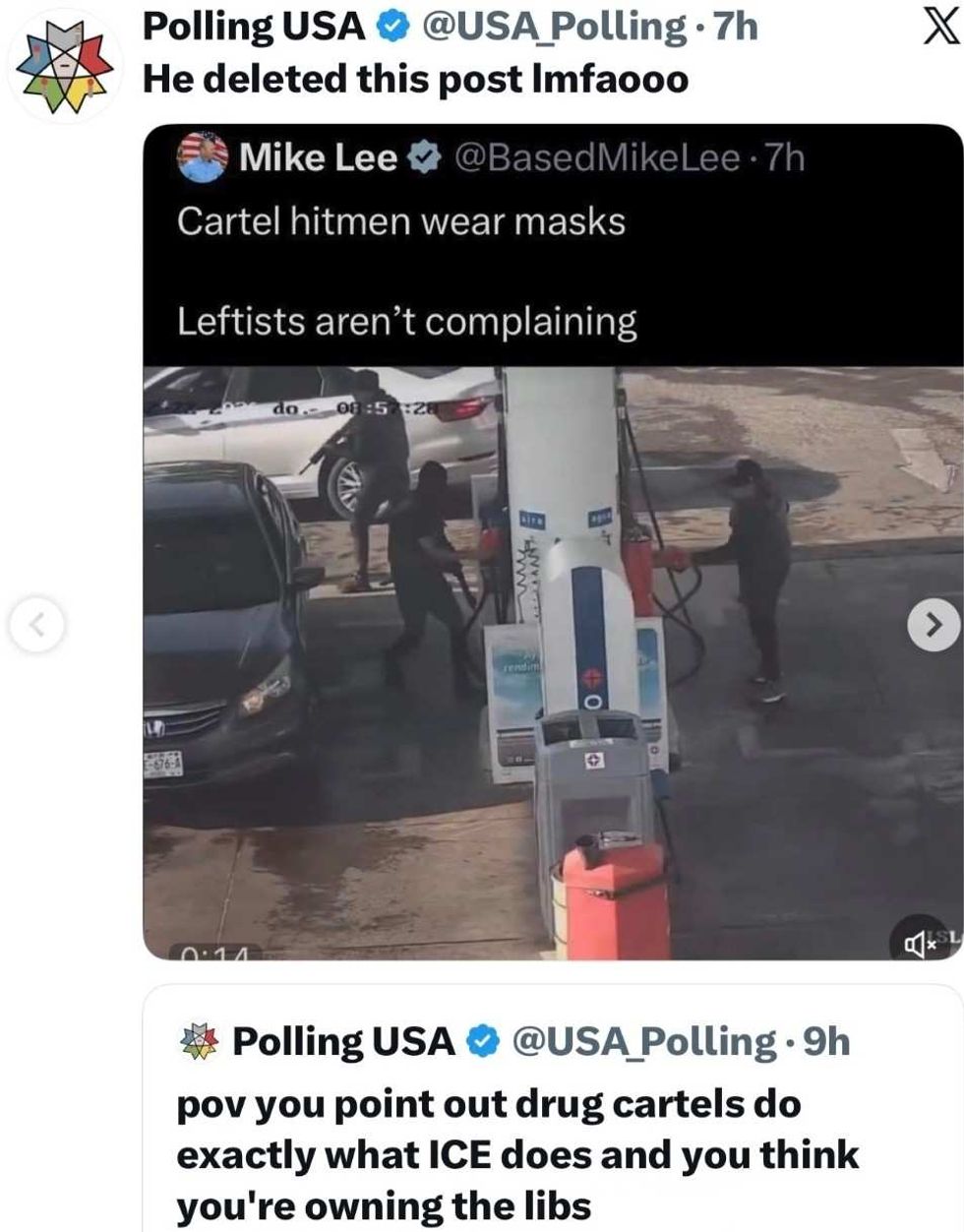

@BasedMikeLee/X

@BasedMikeLee/X @ChrisMurphyCT/X

@ChrisMurphyCT/X @cjoan223817

@cjoan223817

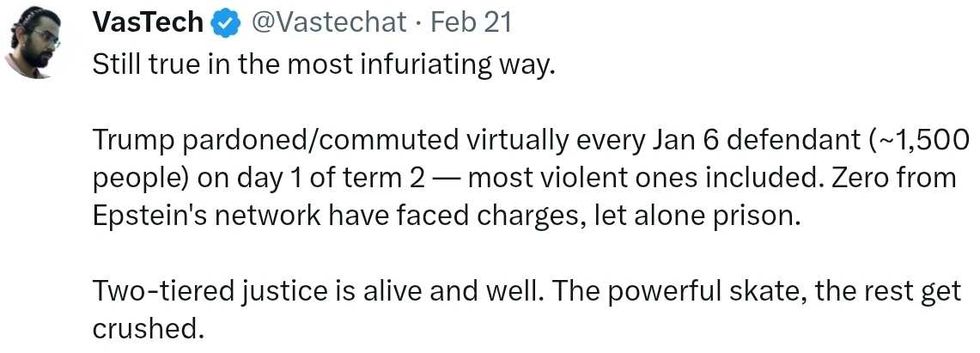

@wideofthepost/X

@wideofthepost/X @mrmikebones/X

@mrmikebones/X @USA_Polling/X

@USA_Polling/X