The Census released key data yesterday, giving states detailed information about their local populations including what percent are racial minorities and where those minorities live. With the information now out and available, states can now finally begin the process of drawing new district lines for elections, with potentially far-reaching consequences for the country due to the prevalence of gerrymandering.

(Map from Cook Political)

All eyes are on how the new district lines will affect the balance of power in the House of Representatives. With only a slim majority, a swing of just five votes towards the GOP will strip Nancy Pelosi of her speakership, slam the brakes on further progressive legislation, and potentially begin a series of retributive hearings and even impeachments against the Biden Administration. With so much at stake, most experts are predicting that the GOP will seek to gerrymander its way to a House majority by focusing their efforts in the states where they control both the legislatures and the governorships, or where they otherwise have a lock on the map-drawing process. These include the key, highly populated states of Texas, Florida and North Carolina, all of which gained seats during reapportionment.

Before we jump into the math of this, let's review gerrymandering. Simply put, gerrymandering is the practice of drawing district lines to favor your party over the other. The best way to understand how this happens is to talk about the two basic forms of gerrymandering: "packing" and "cracking." With "packing" the party drawing the lines concentrates certain types of voters (e.g. African Americans, who vote overwhelmingly for the Democratic party) into districts, effectively forcing them to waste votes that could have made the difference in neighboring districts. "Cracking" is the practice of reaching into districts (e.g. heavily Democratic Austin, Texas) and peeling voters off through clever line drawing and nullifying their votes by connecting them to neighboring districts (Austin for example is split into six districts, only one of them "blue.")

(Map Courtesy of TheFulcrum.us)

Depending on which political pundit you believe, the GOP will enjoy somewhere between 0 and 6—or between 6 and 13—new "safe" seats as a result of this cycle's gerrymandering. Why such an unknown spread? Much depends on what GOP-controlled and Democratic-controlled states actually do—or are even able to do. There are multiple considerations at work, so let's take a look at three.

The GOP is "gerrymandered out."

Because of the highly partisan lines that were drawn in 2010 in places like Texas, there's only so much more than can be squeezed out of new district lines. The GOP was very aggressive in certain states, giving them an extreme partisan advantage. For example, in Wisconsin in 2018 Democrats won every statewide race and a majority of the statewide vote, but due to gerrymandering won only 33 of the 99 seats in the state assembly. The GOP simply may not be able to squeeze that many more winning districts out of the states it controls.

There possibly are more majority-minority districts now.

One lesser known provision of the Voting Rights Act that remains in force today is a requirement that states must keep majority-minority districts (called "minority opportunity districts") together to ensure that they receive some representation. In other words, the GOP cannot so easily "crack" these districts to dilute the power of, say, the Latino or the African American votes there. (The temptation will of course be to either claim a non-racial reason for a line redraw or to "pack" the votes together even more aggressively.) The Census showed a strong increase in the number of Latinos and Asian Americans across America, but the map drawers are only now beginning to look at where they live and whether more districts must be reserved under law. It's a complex process, now largely run by computer algorithms, that is almost certainly going to wind up in court. But a key point is that while the Supreme Court in Rucho v. Common Cause threw up its hands and said it would not involve itself on the question of "partisan" line drawing, leaving that question to state courts to resolve, federal courts still have jurisdiction over racial gerrymandering under the Voting Rights Act. If the GOP gets too aggressive based on racial data provided by the Census, it could wind up with a federal court stepping in to draw the lines—an outcome the GOP would very much like to avoid.

Blue states can gerrymander, too.

While much attention is on red state control over new districts in Texas, Florida, and North Carolina, there are still some blue-controlled states that could, if pressed, draw their lines to counter the GOP. These states include Illinois, New York and Oregon (which gained a seat). There is now an odd dance where blue state legislatures will be looking at possible shenanigans in places like Texas and Florida with the opportunity to respond if they choose. It's a game of political chicken, and it could result in less aggressive—or more aggressive—actions, depending on when states decide to pull the trigger.

Given these competing considerations, it's likely that the number of additional safe seats for the GOP numbers somewhere around six or seven, more than enough to tip control of the House on its own. Democrats will need to rally and turn out in large numbers in a number of key swing districts in order to counter this advantage as well as to offset GOP efforts to suppress votes. Democrats are betting that their hoped-for legislative wins in infrastructure, income support for working families, and expansion of Medicare for the elderly will translate into a rare midterm victory for their party. The GOP, on the other hand, is playing to its base by resisting health mandates and doubling down on the politics of division on issues like critical race theory, trans girl athletes, and immigration. There are also wild cards, including Trump and the pandemic, which could play significantly into voter attitudes and turn out in 2022.

As states begin to announce their new maps, expect to see immediate litigation from both sides, in many cases playing out in the local courts where the make-up of the state supreme courts will have an outsized impact. Expect also to see a great deal of handwringing from both parties over whether minorities must or should be lumped together in majority-minority districts, especially as demographic voting patterns among Latinos begin to shift and it becomes clearer that many white voters in those districts vote more along party than racial lines.

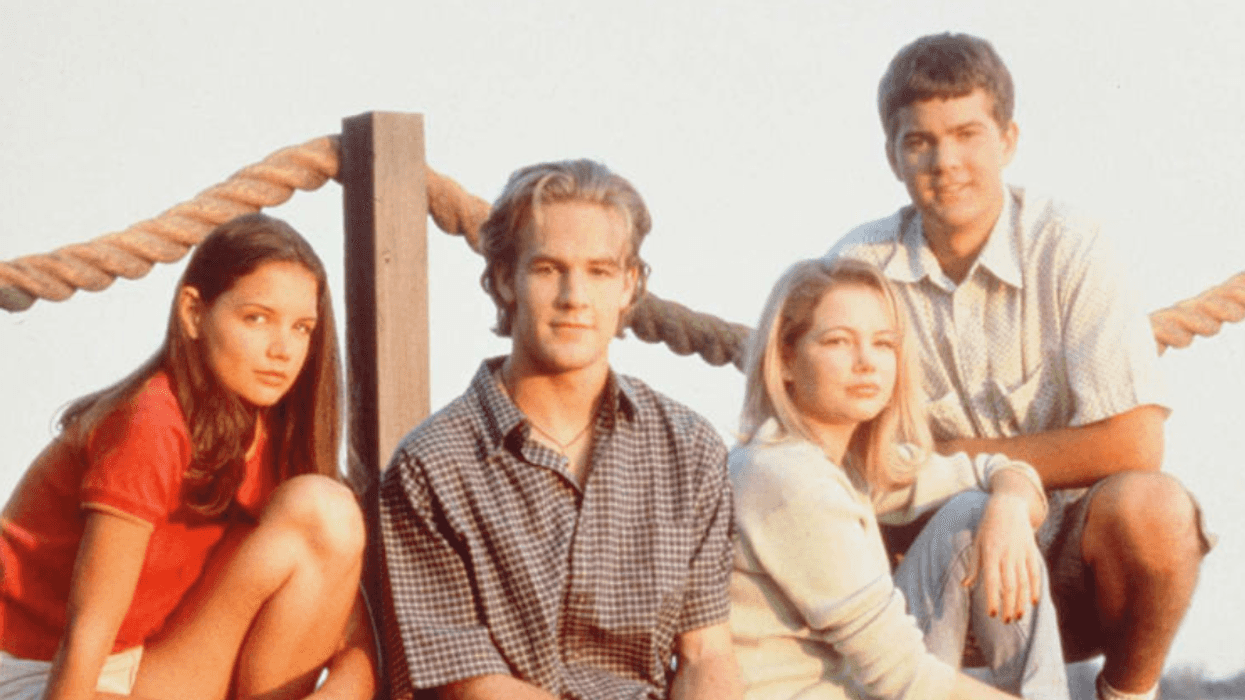

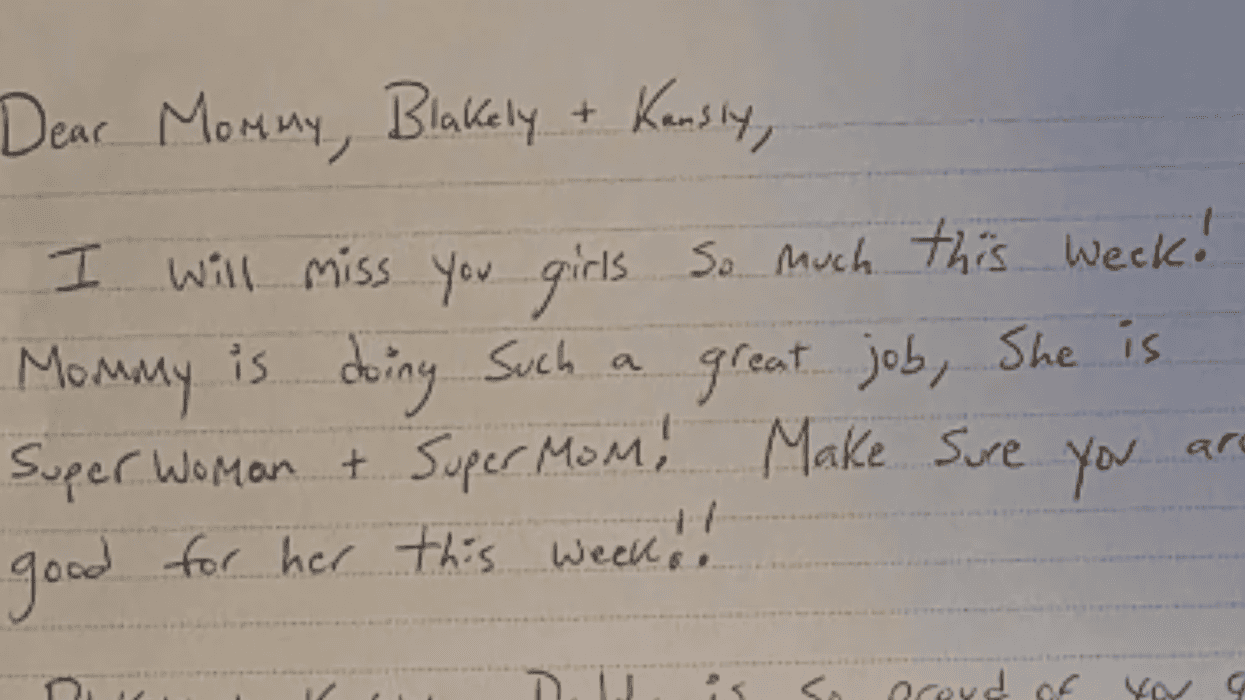

@jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram

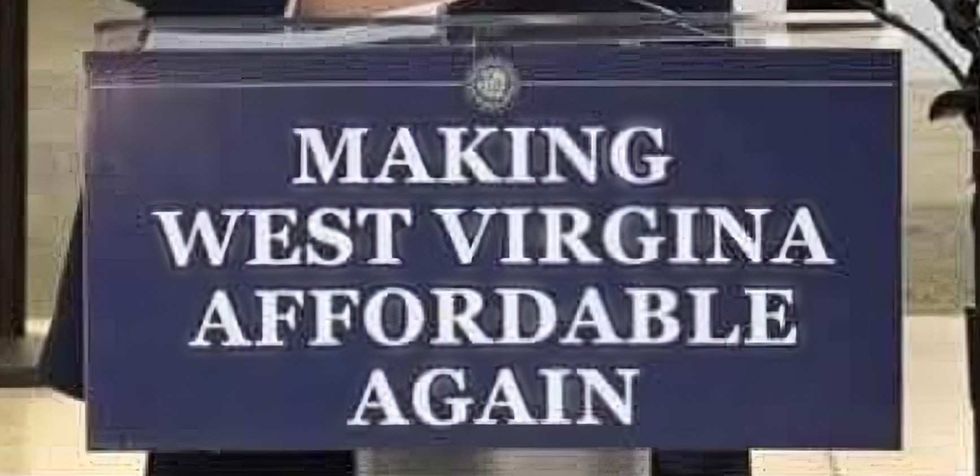

@ameliaknisely/X

@ameliaknisely/X WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook