It’s one of the most gripping rites of spring. The switch to daylight saving time? Nope. The onset of seasonal allergies? Nah.

We’re talking March Madness, the NCAA’s college basketball tournament. It’s a glorious couple of weeks during which almost everyone – except maybe your great aunt – becomes an expert on college basketball. Across the country, millions of people will participate in March Madness office pools, filling out brackets and laying down cash. And according to outplacement and executive coaching firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas, Inc., employees’ monitoring of their bracket’s progress will contribute to an estimated $2.3 billion in lost productivity during the tournament.

March Madness is big business. Some $10 billion will be wagered on this year’s tournament, of which only about $300 million will be done legally via sports books in Las Vegas, according to the American Gaming Association. The NCAA will get paid $8.8 billion by CBS Sports and the Turner cable sports networks for the broadcast rights for the tournament through 2032. The cities and venues that host the various rounds of the tournament also realize massive economic windfalls, as do their hotels and restaurants.

And, of course, the coaches of big-time college sports programs make money. Lots of it. For example, Alabama Crimson Tide football coach Nick Saban – with six national championships to his name – will be paid just over $11 million this year and is the highest paid coach in all of college athletics. In basketball, the current top earner is Duke Blue Devils coach Mike Krzyzewski. Since 1980, “Coach K” has led the Blue Devils to five NCAA championships and will be paid $5.5 million this year for his efforts. (Duke, with a 26-7 record, is the number two seed in the NCAA Midwest bracket this year.) Another “fun fact:” the three highest paid state employees in Maryland are the coaches of the University of Maryland’s men’s basketball, football and women’s basketball teams, respectively.

Where’s the Fairness?

But there’s one group that doesn’t rake in the cash from March Madness or other college athletics: the student athletes who actually play the games that generate those billions of dollars. NCAA eligibility rules prohibit student athletes from being paid. They also cannot be paid for endorsements. Elite college athletes often are recipients of athletic scholarships, their ticket to the opportunity for a college education. But the overwhelming majority of college athletes, including “walk-ons” who try out and make a team based on their demonstrated talent, play purely for their love of the sport. They’re fully aware they never will parlay their college careers into a professional sports career. (According to the NCAA, only 1.1 percent of men’s basketball players and just 1.5 percent of football players stand any chance of making it to the pros.)

One former football standout for the Villanova Wildcats, Lawrence “Poppy” Livers, has instituted legal action that could upend the economic dynamics of college athletics. In October 2017 Livers filed a federal class-action lawsuit in Pennsylvania against the NCAA and 20 universities that argues that student athletes qualify as employees under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). His contention is that student athletes who receive scholarships are employees who deserve compensation because those scholarships require them to participate in NCAA athletics under daily supervision of full-time coaching and training staff. Livers posits that student athletes are as much employees, if not more than, student ticket takers, seating attendants and food concession workers at NCAA athletic contests.

Students or Slaves?

Unsurprisingly, the NCAA has sought to dismiss Livers’s suit. The basis of that requested dismissal, however, is highly offensive to some. In its opposition, the NCAA is relying on one particular legal case, Vanskike v. Peters. Daniel Vanskike was a prisoner at Stateville Correctional Center in Joliet, Illinois, and Howard Peters was the director of the Illinois State Department of Corrections. Vanskike and his attorneys argued in 1992 that the prisoner should be paid a federal minimum wage for the work that he was required to do while incarcerated.

The court decided against Vanskike, citing a “carve out” in the 13th Amendment to the Constitution: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

In response to the NCAA’s motion to dismiss, Livers’s attorneys held nothing back: “Defense Counsel’s insistence that Vanskike be applied here is not only legally frivolous, but also deeply offensive to all Scholarship Athletes – and particularly to African-Americans. Comparing athletes to prisoners is contemptible.”

Shaun King, a Brooklyn-based columnist for The Intercept who focuses on civil and human rights, racial justice, mass incarceration and law enforcement misconduct, takes an unflinchingly harsh view of the NCAA’s position: “The body that runs college sports wants to use a justification for the slave labor of convicted criminals to justify its outrageous greed. This is not just bad optics. It gets to the heart of what the multibillion-dollar enterprise that is the NCAA thinks not just of its athletes, but of its core business model. It is, in essence, admitting that student-athletes are working as slave laborers and, as such, do not deserve fair compensation. Bigotry has a way of revealing itself. And that is exactly what the NCAA — by leaning on the case of a prisoner demanding that he be paid as its justification for denying their athletes a wage of any kind — has done here.”

The debate over whether student athletes should be paid is not new. In 2014, University of Connecticut’s Shabazz Napier, who led the UConn men’s basketball team to an NCAA championship, revealed that he sometimes went to bed “starving” because he couldn’t afford food. During that championship year, UConn's men's basketball program generated a $1 million profit for the school.

Napier said he wasn’t looking for a huge payday. "I just feel like a student-athlete, and sometimes, like I said, there's hungry nights and I'm not able to eat and I still got to play up to my capabilities. ... When you see your jersey getting sold — it may not have your last name on it — but when you see your jersey getting sold and things like that, you feel like you want something in return."

So as you watch the progress of your bracket in the coming days, keep in mind that your fortunes may be built on the backs of student athletes who will never realize one. And may go to bed hungry.

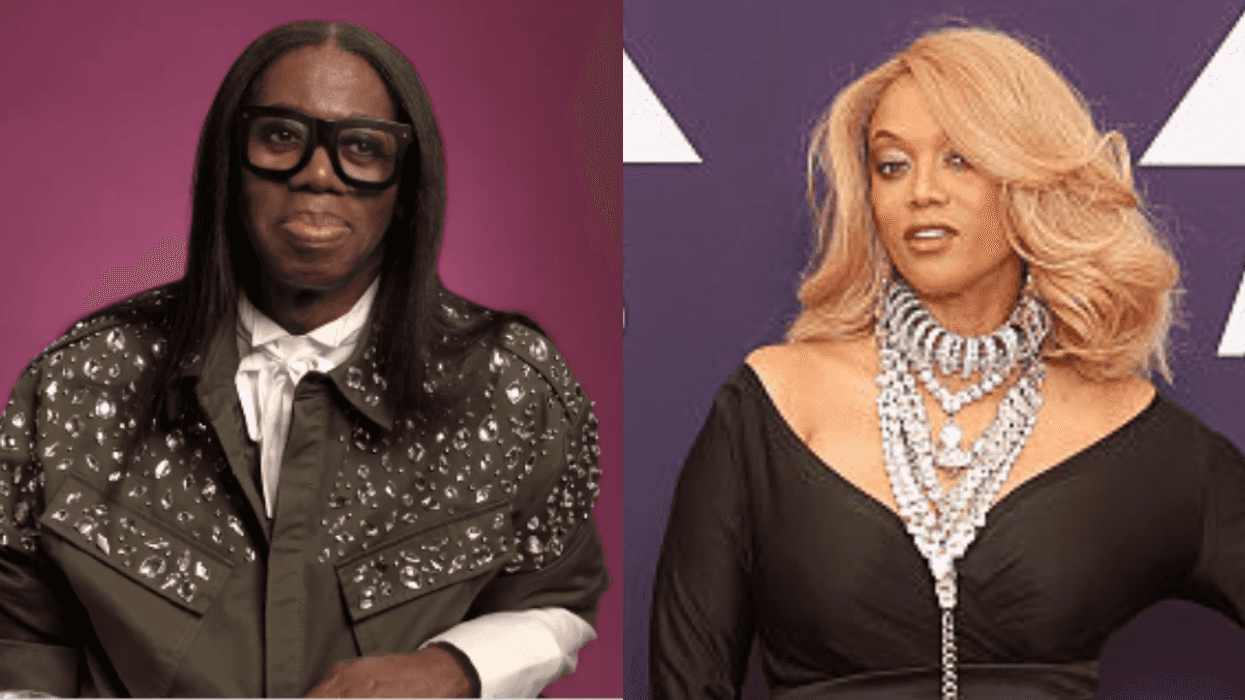

@lamorne/Instagram

@lamorne/Instagram @bigbeaubrown/Instagram

@bigbeaubrown/Instagram @musiccitykristy/Instagram

@musiccitykristy/Instagram @phil_torres/Instagram

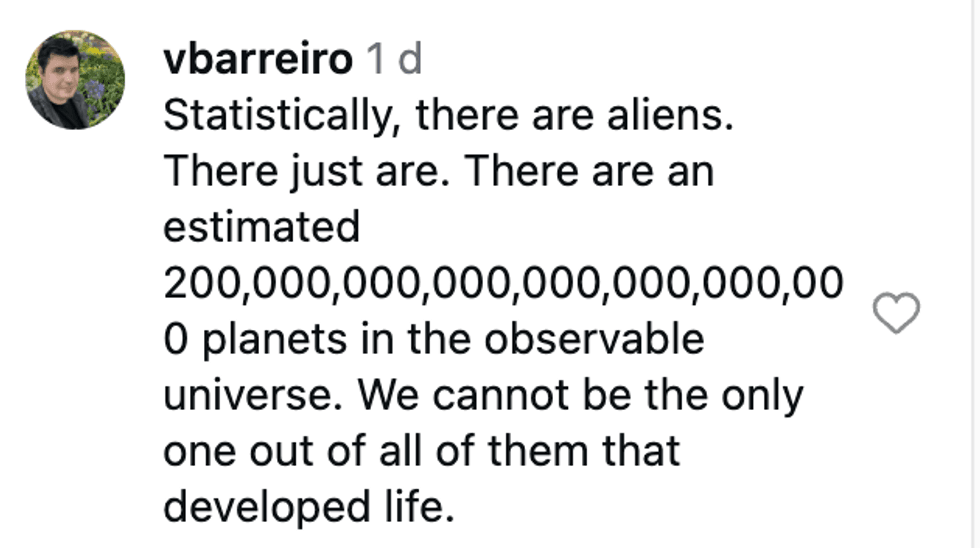

@phil_torres/Instagram @vbarreiro/Instagram

@vbarreiro/Instagram @franklinjleonard/Instagram

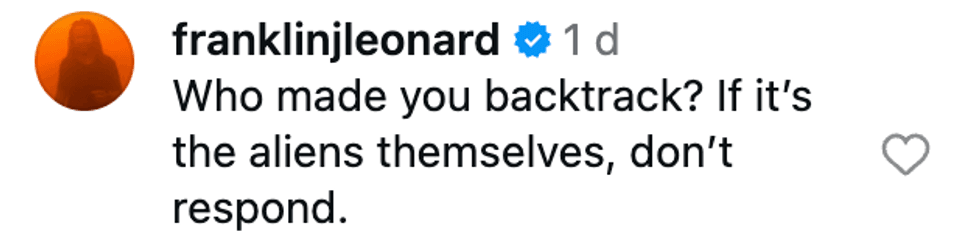

@franklinjleonard/Instagram @br1an02/Instagram

@br1an02/Instagram @ohhelloitsmax/Instagram

@ohhelloitsmax/Instagram @frecklesmarie/Instagram

@frecklesmarie/Instagram

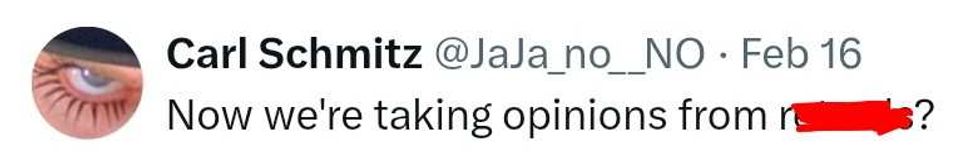

@JaJa_no_NO/X

@JaJa_no_NO/X @CWMorgan1000/X

@CWMorgan1000/X reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram