SECOND NEXUS PERSPECTIVES

The following story is personal and gross. That’s why I’m sharing it. I was diagnosed with severe ulcerative colitis right before my 29th birthday. Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an autoimmune disease in which the immune system attacks healthy tissue in the colon. UC is a chronic, inflammatory disorder with no agreed-upon cause and no known cure. It is closely related to Crohn’s disease, except Crohn’s disease affects the entire digestive system, rather than just the large intestine and rectum. People with IBD also suffer from PTSD, myself included.

Inflammatory bowel disease, which includes Crohn's and ulcerative colitis, is reaching epidemic levels in the United States, particularly among young people. After two years of trial and error with various medications and therapies, I opted for a three-stage surgery to remove my colon and regain control of my life. I just had my second surgery, which involves rerouting my small intestine into a “j pouch,” which will function as a new colon and rectum. I’ll have to wear an ostomy bag for only another three months. After being released from the hospital, I subsequently ended up in the ER, again, with a bowel obstruction. The English language lacks the appropriate terminology to describe how painful bowel obstructions are, especially when your abdomen is being held together by staples. Thankfully, however, it resolved itself without needing corrective surgery. And I got all the dilaudid I wanted.

Ulcerative colitis is not just as awful as it sounds––it’s worse. Never mind the complications it causes outside the gut, like arthritis, anemia, weight loss, and fatigue. Never mind the never-ending trips to the bathroom. I want to talk about the day-to-day misery that IBD inflicts upon its victims.

We’ve all seen the TV commercials for drugs like Humira and Entyvio, which are biologics that target inflammation. In the ads, people are smiling and playing sports, joking with their doctors, being allowed in pools; they’re doing things that are not feasible when UC is flaring. Biologic treatments also require months to take effect, if they work at all. Patients also have to get regular infusions, indefinitely. UC also leads to sexual dysfunction, in part from ongoing physical trauma, but also due to nutrient depletion and, in my case, long-term use of high doses of prednisone. The PTSD doesn’t help matters, either.

In the year leading up to my diagnosis, there were plenty of warning signs that something was very, very wrong with my body. The number of times per day I was going to the bathroom was steadily increasing, as was the presence of blood in the toilet. Stubborn primate I am, I assumed that my issues stemmed from working out too hard or not having enough fiber in my diet. Even though I was in the bathroom about six times per day, I was still able to go about relatively normally. It was in the fall of 2015 when my world began to implode. At the time, I was enjoying my career as a commercial real estate broker. I was a partner at my own firm, and I had a team of agents working for me.

A fateful September day was just the beginning.

It was a warm, sunny day in early September. My morning began just like any other; I got up around 9:30, got dressed, and headed out to meet a client for an office showing. As I exited the 1 train at 28th street, my gut began to cramp. I had a feeling that something terrible was coming. My half-block walk to my destination felt like a mile. I arrived at the building and asked the doorman where the bathroom was, and I plunged into the elevator. During my ascent to the third floor, the urge to “go” became overwhelming. I was sweating and shaking, and my fellow passenger asked me if I was okay. “It’s just the caffeine from my coffee,” I said, not fooling anyone, given that I was trembling like I had the DTs.

The elevator doors opened, and I barreled down the hallway. I didn’t make it to the bathroom. My innards unleashed their fury, and I was powerless to stop it. That’s right; I crapped my pants five minutes before my client was due to arrive. Surprisingly, I didn’t panic; after all, I didn’t have much choice other than clean myself and my clothes as best I could. Thankfully, my client was running about ten minutes late. I performed the most incredible act of poop ninja-ing, a skill which I have now pridefully mastered, and was able to complete my tour. Then I called it a day and went home. Not only was I traumatized, I felt terrible. I was dizzy and tired, and every muscle in my body ached. Little did I know this was to become my new normal. (Oh, by the way, the client didn’t end up leasing any space. Go figure. Incidents like this would continue to plague me until I had my colon removed.)

The quality of life I had enjoyed ended abruptly. Seemingly overnight, I became a prisoner in my own home and my own body. It’s difficult to adequately describe what daily life is like with ulcerative colitis, as the disease affects everyone differently. As I would come to learn, my case was more severe than most, a realization that took a lot of time.

Ulcerative colitis is like no other disease. Symptoms can appear and disappear, with no discernible trigger. There are good days (or should I say, days that are less bad), and there are really bad days, but because the way UC affects each day is unpredictable, trying to run my life was a constant challenge.

The reality is, merely scrounging up the strength to even go to the doctor is a feat in and of itself.

There were many instances in which I had to cancel doctor visits because I’d shit my pants en route. One day, I was walking to the store to grab some juice as I headed for an appointment (juice was better than water because it contains electrolytes and sugar). I ended up barreling up the stairs to the store’s bathroom, but I didn’t make it. I split open my legs falling up the stairs, and upon finally making it to the bathroom, realized it was out of order and the toilet didn’t flush. I still pity the poor soul who had to… um… clean up the disaster zone. I crapped my pants while attempting to jog and workout more times than I can or care to count. I would regularly not make it to meet clients. Going to the office was something I was able to muster maybe once a week. My business was imploding, and my finances fell into ruin. In a few short months of not being able to generate income, my credit score plummeted from 740 to the low 500s. I had to live off credit cards but had no way to pay them back. At one point, I had to borrow money from my boss to make my rent. Inflammatory bowel disease is financially cataclysmic.

While I did occasionally make it out to the occasional party or event, half of those nights ended early because I couldn’t control my bowels while either waiting in line or once inside the club. For me, there were far more bad days than not-as-bad days. Mornings were the worst; instead of being woken up by an alarm, the urgency to use the bathroom would spring me out of bed, usually between 5 and 7 am. My first daily trip to the bathroom was typically quick, but extremely painful and very bloody. Amazingly, the urgency wasn’t even my biggest frustration; rather, it was the monotony of going, leaving the bathroom, and then having to go again immediately, sometimes multiple times within the span of only a few minutes. The pain, the strain, and the blood loss left every muscle in my body aching and my head spinning.

Serious planning was involved on days when I absolutely had to leave my apartment. I had to time when to eat and shower, had to budget bathroom time for if/when I got to my destination, and I needed an escape plan in case of emergency. This made simple tasks like going to the store, only half a block away, require a literal itinerary — and often a chaperone. And that’s not including the pain I know I’d have to muscle through. Many days, I just gave up. I stayed home, had everything delivered to me, and had to outsource meetings with clients. Life was miserable and painful. I’m not religious, but there were numerous occasions where I would pray for death. Making matters worse were the long trial periods that each medication required, which ranged from weeks to months, ultimately leading nowhere. I only got worse, and more desperate.

“We’re sorry, but our bathrooms are for customers only.”

Living in New York City made life with UC unbearable. My biggest fear was getting stuck on a subway train, and because there are so few public bathrooms or businesses that open their facilities to the public, I was often left helpless in humiliating situations involving lack of bathroom access. Denying people access to bathrooms is degrading and dehumanizing. People with IBD and other digestive disorders, like IBS, often have nowhere to go when out and about in the city. This is completely unacceptable, and most establishments aren’t aware that denying someone with a disability access to a bathroom is illegal and discriminatory. Despite my pleas, I was most often turned away, even when the restaurants were empty.

Dear NYC businesses: do better. I wasn’t exaggerating when I said, “I’ll shit on your floor if you don’t let me in, as I have IBD and can’t hold it.” The staggering lack of empathy was demoralizing, and any employee who pulls this nonsense deserves to be fired for discriminatory behavior. It’s not only a serious breach of human etiquette, it’s illegal.

When I was flaring at my worst, I could barely make it to the diner at the end of my block. There were days I was too sick to leave my bed. More often than not, I’d be trapped in the bathroom for hours on end, sometimes several times per day, and often in a public place. Imagine being in a restaurant or bar that only had one or two single-occupancy bathrooms. Now imagine having to wait in line when the floodgates were about to burst. Penn Station was my most frequent public dumping site; anyone familiar with the facilities in the United States’ busiest transit hub knows how disgusting they are.

Dating, socializing, traveling and even showering was often impossible. UC flare-ups often landed me in the emergency room, requiring powerful steroids and pain medication. My wardrobe took a hit too; dark colors were the only fail-safe I had in “just in case” emergency scenarios, of which there were literally hundreds.

Colonoscopies really aren’t so bad.

If you’re approaching 30, a colonoscopy is a must. The procedure itself is quick and painless, as you’re given anesthesia and are asleep through the 45-minute medical spelunking. Honestly, propofol is awesome; a silver lining, I guess. Prepping for a colonoscopy is gross and annoying, but in a weird twist of irony, feels good when you have UC. The night before the procedure, you must drink a gallon of what is basically Drain-O for your gut. For sufferers of UC, this can be rather therapeutic. Despite it tasting like lemony seawater, it cleans you out and then you go to sleep. It just requires about three hours of being in the bathroom, which for me, wasn’t anything unusual. It’s best to schedule your appointment early the next morning so you can start eating again, as you’ll be pretty hungry by this point. Once it’s over, you go home and rest for a few hours. I’ve had a total of six colonoscopies, and since I no longer have a colon, I’ll never have a colonoscopy again.

You can be a part of the solution.

First, don’t deny people access to a bathroom at your place of work. If a customer or guest is begging, they will look like they are in pain. Let them use your bathroom. Talk to your family and your doctor about any weird gut issues you may be having. Usually, it ends up being nothing major, but catching this disease early is the key to getting it under control. Don’t ignore blood. Don’t ignore pain. Don’t ignore increasing trips to the bathroom. Don’t ignore constant diarrhea or constipation, both of which are prominent symptoms of UC. But most of all, don’t be afraid to ask friends or family for help. You have absolutely nothing about which to be embarrassed or ashamed. Everybody poops, and poop is a direct indication of what’s going on in your body. Monitor it, listen to your body, and don’t ignore abnormalities in your gut.

@bradley.brown.7355/Facebook

@bradley.brown.7355/Facebook @jonathan.d.thomas.3/Facebook

@jonathan.d.thomas.3/Facebook @WrnrG/Facebook

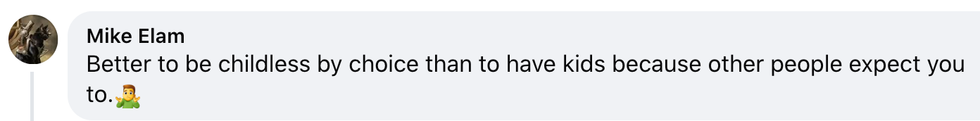

@WrnrG/Facebook @mike.elam.919426/Facebook

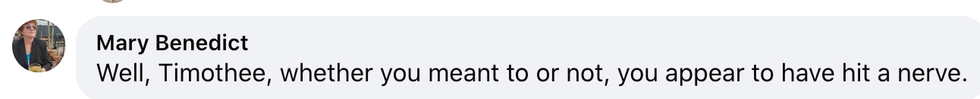

@mike.elam.919426/Facebook @MaryBenedict/Facebook

@MaryBenedict/Facebook

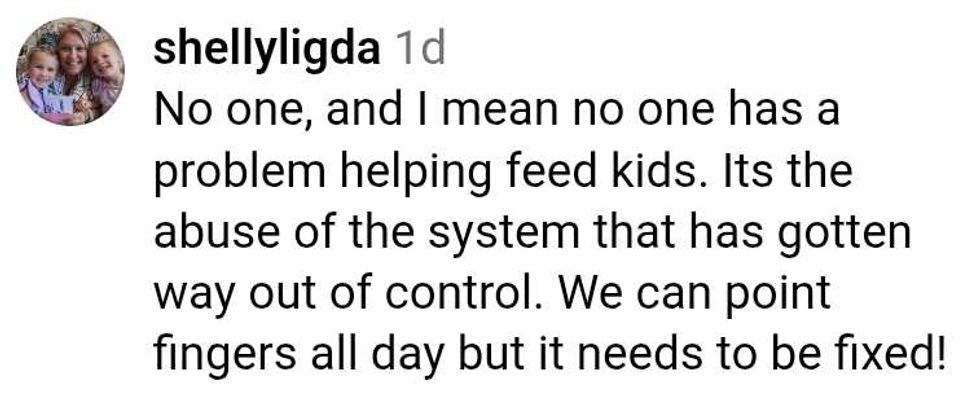

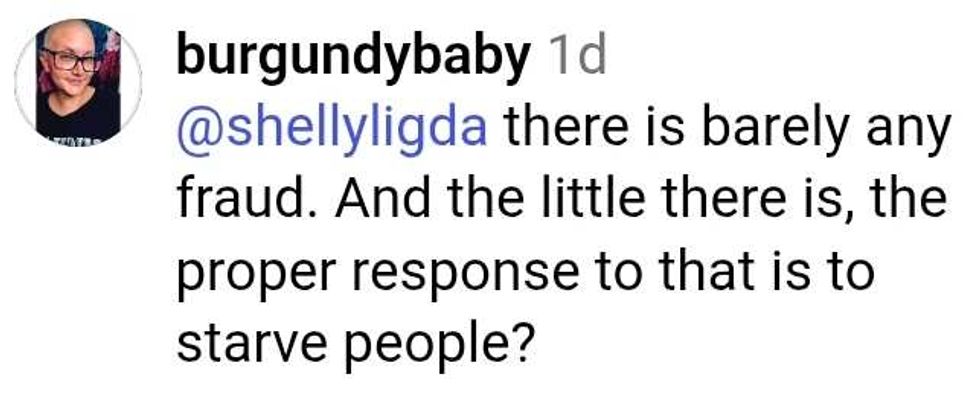

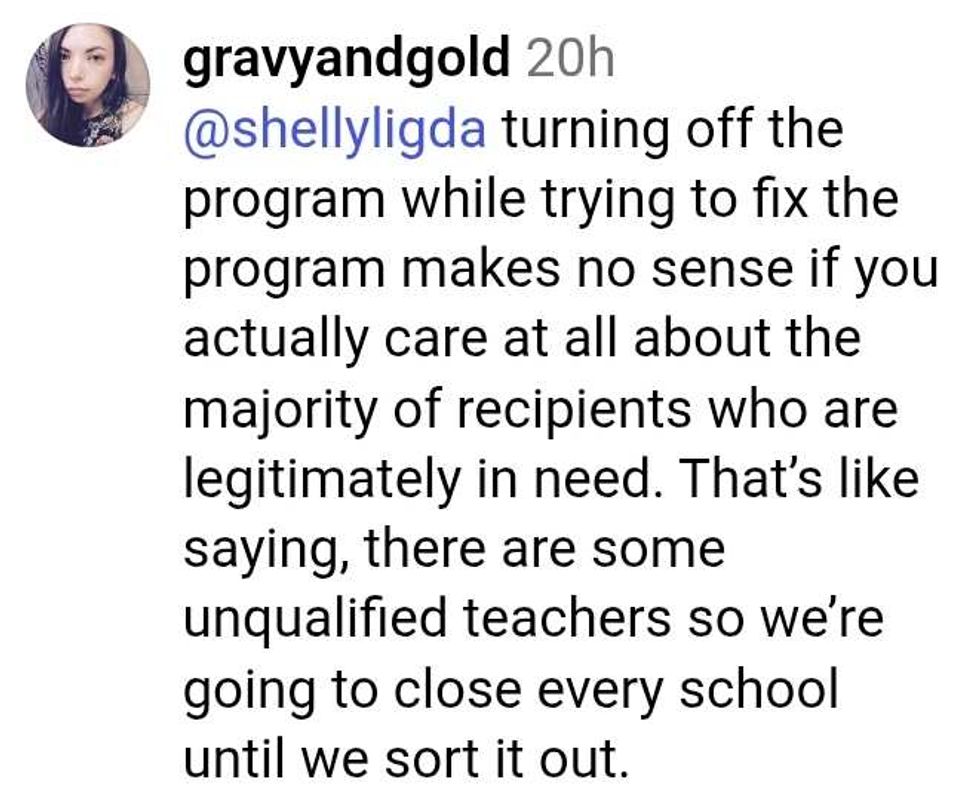

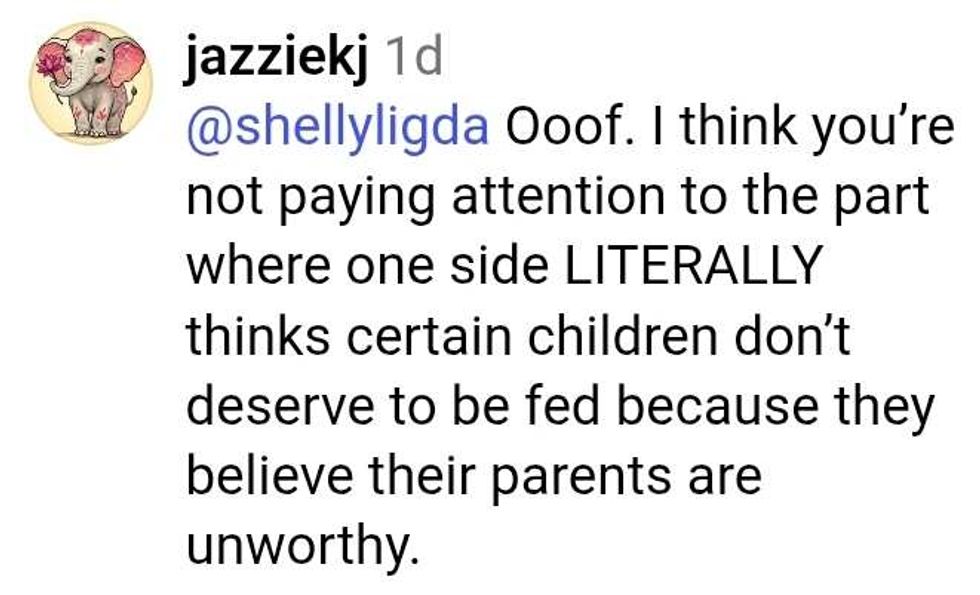

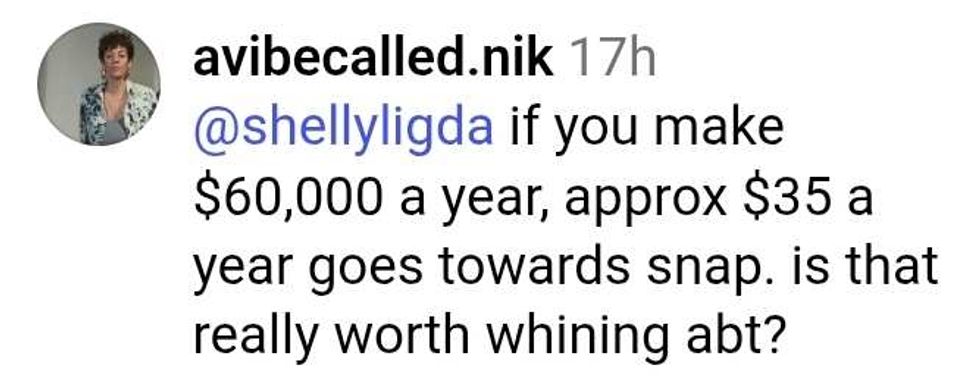

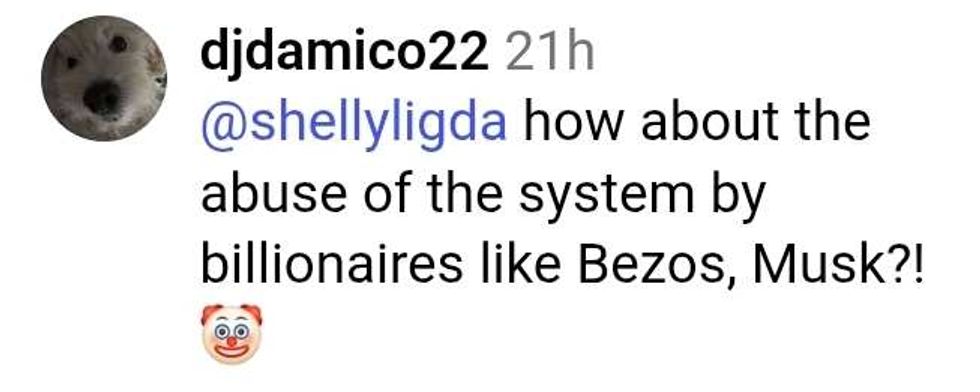

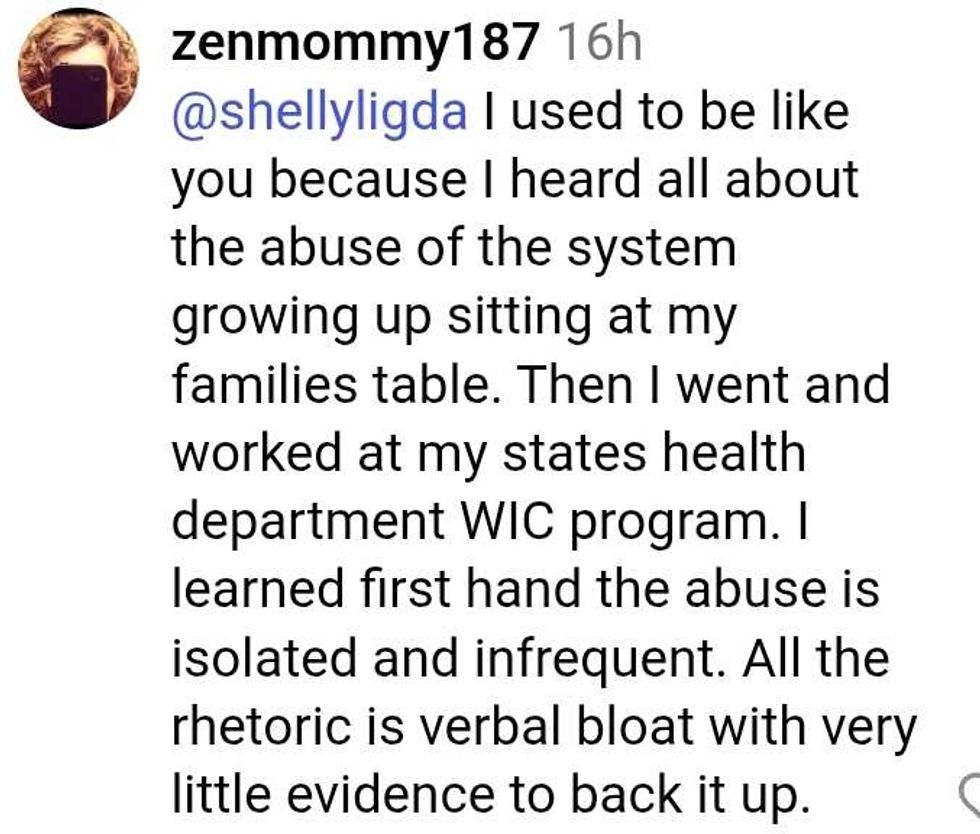

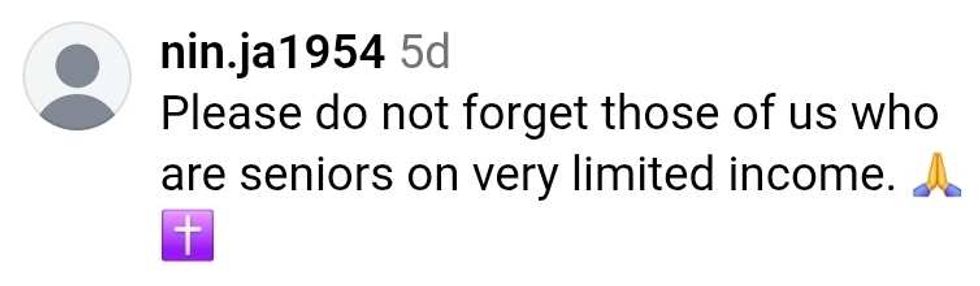

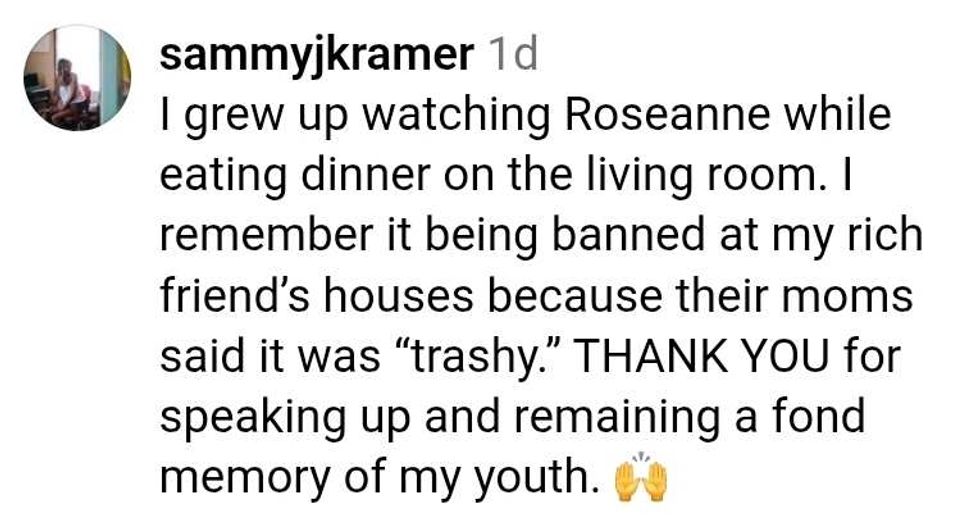

@reelmfishman/Instagram

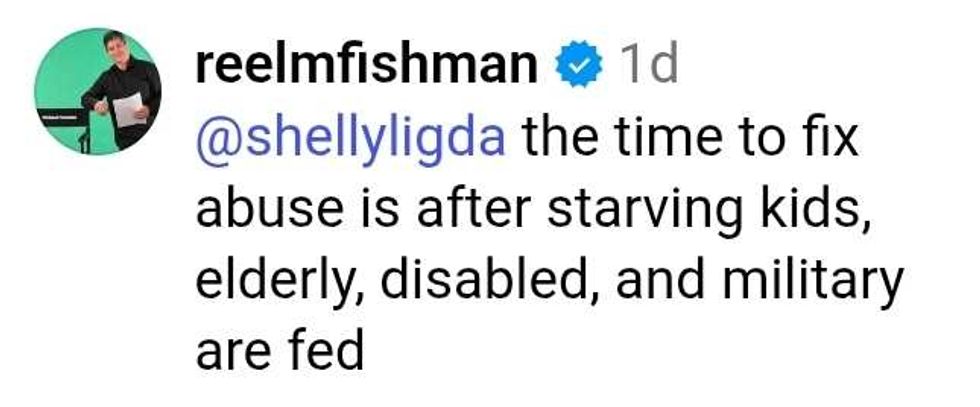

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram @reelmfishman/Instagram

@reelmfishman/Instagram

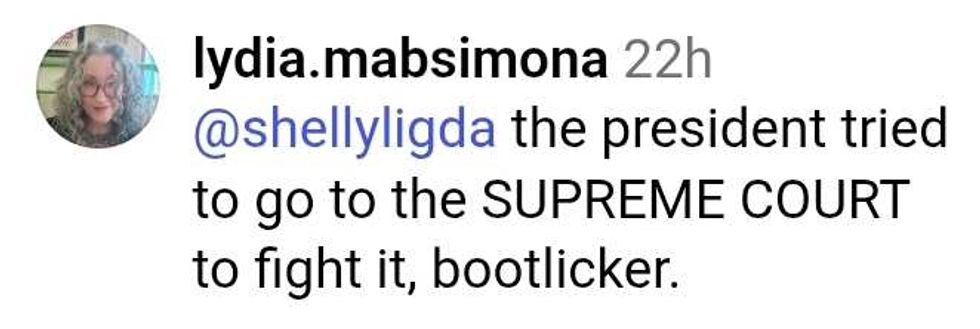

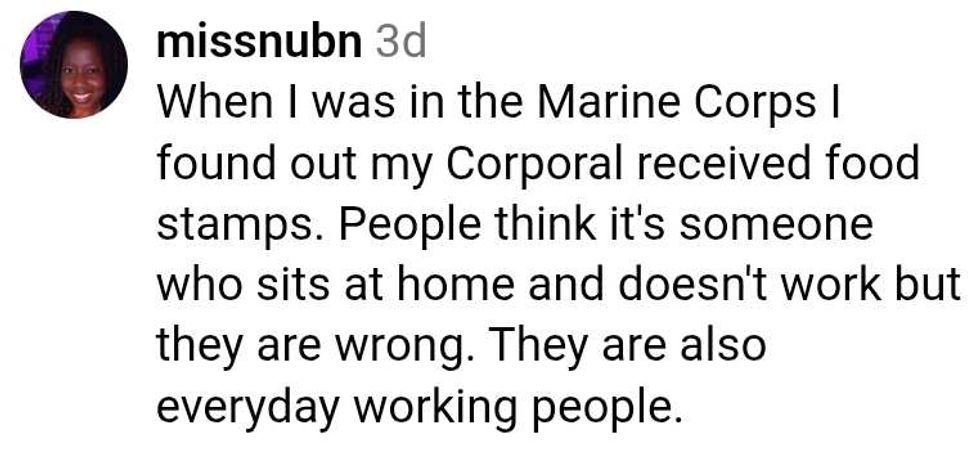

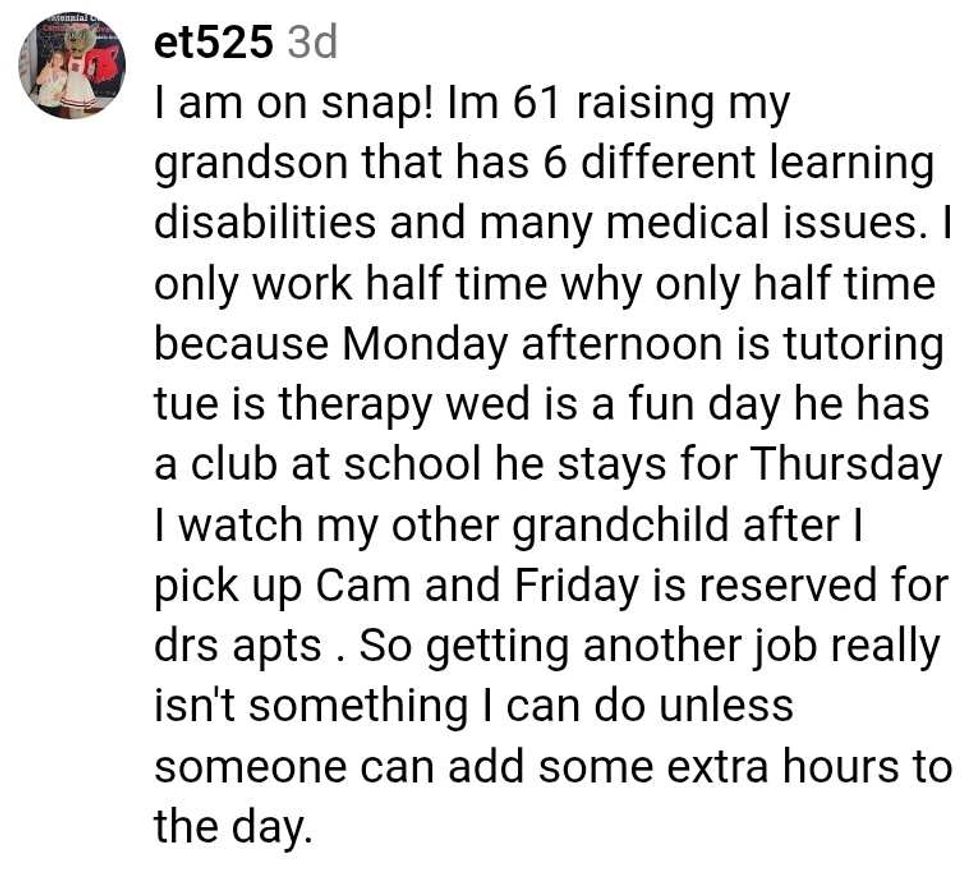

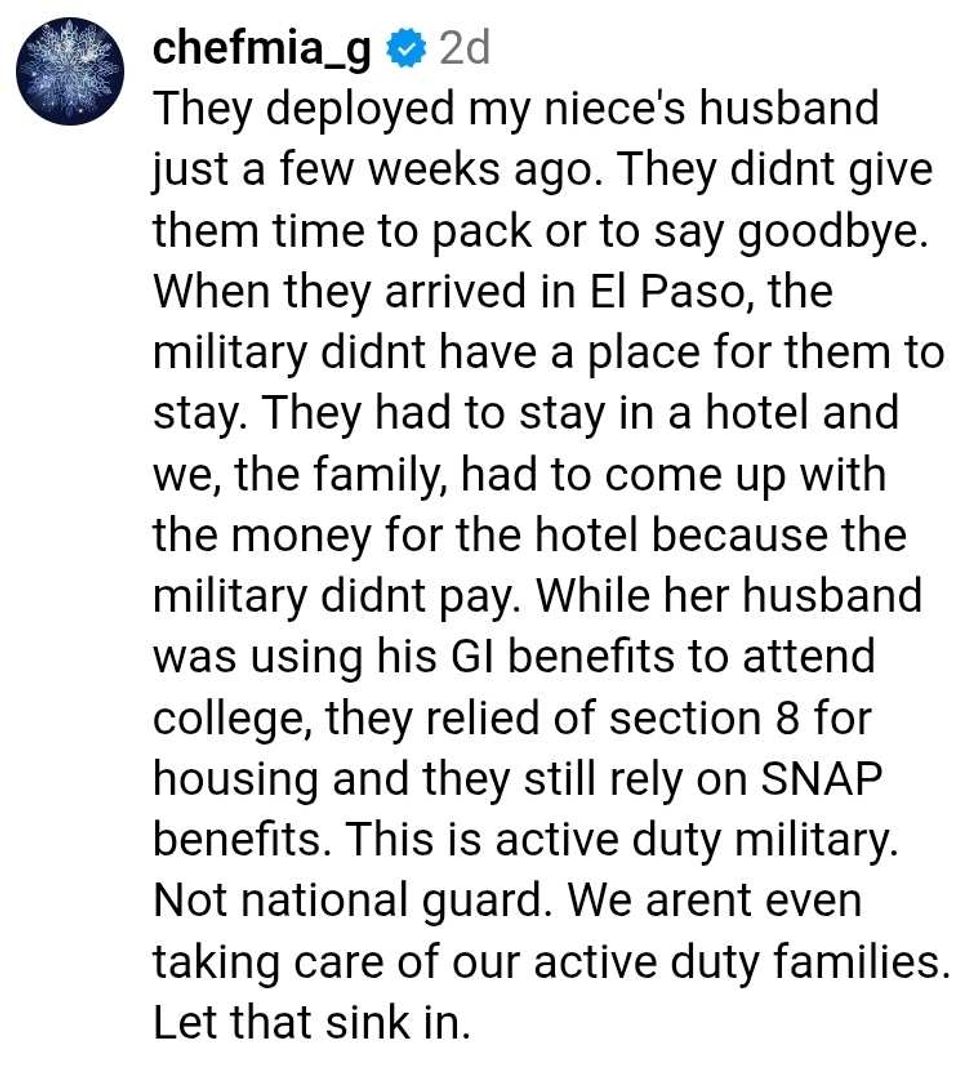

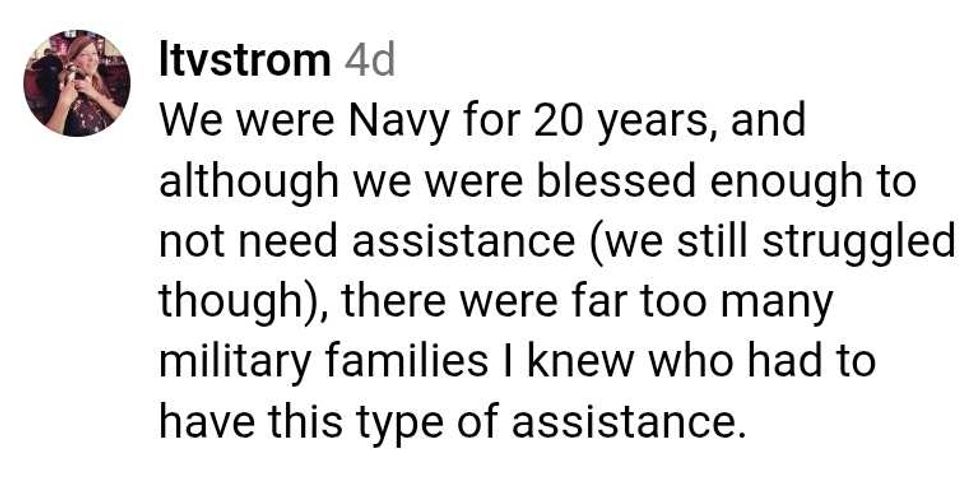

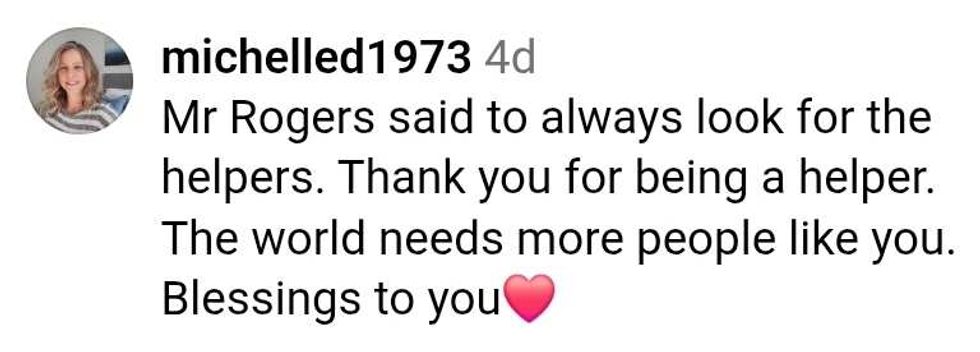

@TomiLahren/X

@TomiLahren/X