In 1987, Florida adopted the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) as its official reptile. Who could have foreseen that three decades later this stately, scaly, once endangered creature would find itself at the center of a thriving “marsh to market” economy generating around $7.6 million for the state per year, let alone an ensuing crime ring?

This spring, a peculiar case shed light on Florida’s highly lucrative, highly regulated alligator farm industry, as well as on a ring of alleged gator egg poachers. State’s Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission officers concluded a four-year sting operation this May with the arrests of nine men alleged to be poachers, the largest investigation of its kind. Nicknamed “Operation Alligator Thief,” the sting snared the men on 44 felony charges collectively, including stealing, racketeering and falsifying court records; court proceedings will likely commence in early 2018.

To carry out their undercover operation, two officers using the aliases Curtis Blackledge and Justin Rooks played the part of legitimate alligator farm operators, opening Sunshine Alligator Farm in DeSoto County. As the Commission’s Lt. George Wilson described it: “Land was leased, licenses obtained, infrastructure built to create a fully functioning alligator farm. Alligator stock was legally purchased from other alligator farmers to build the business and facilitate business contacts...The alligator farm established business credibility for the (undercover) officers to infiltrate the criminal element."

Posing as Blackledge and Rooks, the officers first established a trusted network of industry contacts via trade shows and business meetings. They then let it be known that they’d be willing to purchase illegally harvested gator eggs, and eventually were invited to attend illicit harvesting expeditions. Over the course of the sting they documented more than 10,000 eggs being taken from nests without proper permits; even when individuals had permits, they often took far more eggs than allotted, did not have a state-required wildlife biologist present, and forged follow-up paperwork.

For investigators, the sting was not solely to demonstrate the commission is getting tough on crime but to send a message about poaching’s potentially devastating statewide impacts: "Their crimes pose serious environmental and economic consequences. These suspects not only damage Florida's valuable natural resources, they also harm law-abiding business owners by operating black markets that undermine the legal process,” said Maj. Grant Burton, head of the agency's Investigations Section.

Florida, the second largest home to gators after Louisiana, boasts around 1.3 million American alligators and over 90 licensed alligator farms, but the species’ fate did not always look so bright. Just before the Civil War, local trappers began selling gator hides to meet appetites of a Parisian fashion industry hungry for gator boots and bags. Soaring demand (an estimated 10 million alligators were killed between 1870 and 1950) devastated the population, leading the reptiles to be classified as a federally endangered species in 1967, with numbers hovering in the thousands.

Through extensive protections, including the criminalization of unofficial egg harvesting, as well as the taxing of licensed gator farmers to fund conservation efforts, gators now thrive in the Sunshine State. Via careful regulation, alligators raised on farms have since grown into a hugely valuable commodity for purposes ranging from fashion to food. Florida egg values skyrocketed recently, following flooding in Louisiana which has devastated gator nests in recent years, raising an average gator egg’s price point from just $4-8 up to an incredible $70 a pop and leading to a surge in crime amongst profit-hungry poachers.

Licensed owners of gator egg permits can rest easy for now, as poachers will likely lie low following the spate of sting-related arrests. One such owner, Allen Register, also an official “public water egg collection coordinator,” co-owns popular attraction Gatorama, where families can watch gators hatch and play around with the newborns. In 2015, burglars stole $66,000 worth of gator eggs from a Gatorama incubator. Register has a message for would-be poachers, whom he feels are a “black eye on the industry.” Simply put, “Poaching is not worth the risk of getting caught.” Florida wildlife officials surely hope their crackdown sent the same message, and that poachers will think twice before stealing a gator egg.

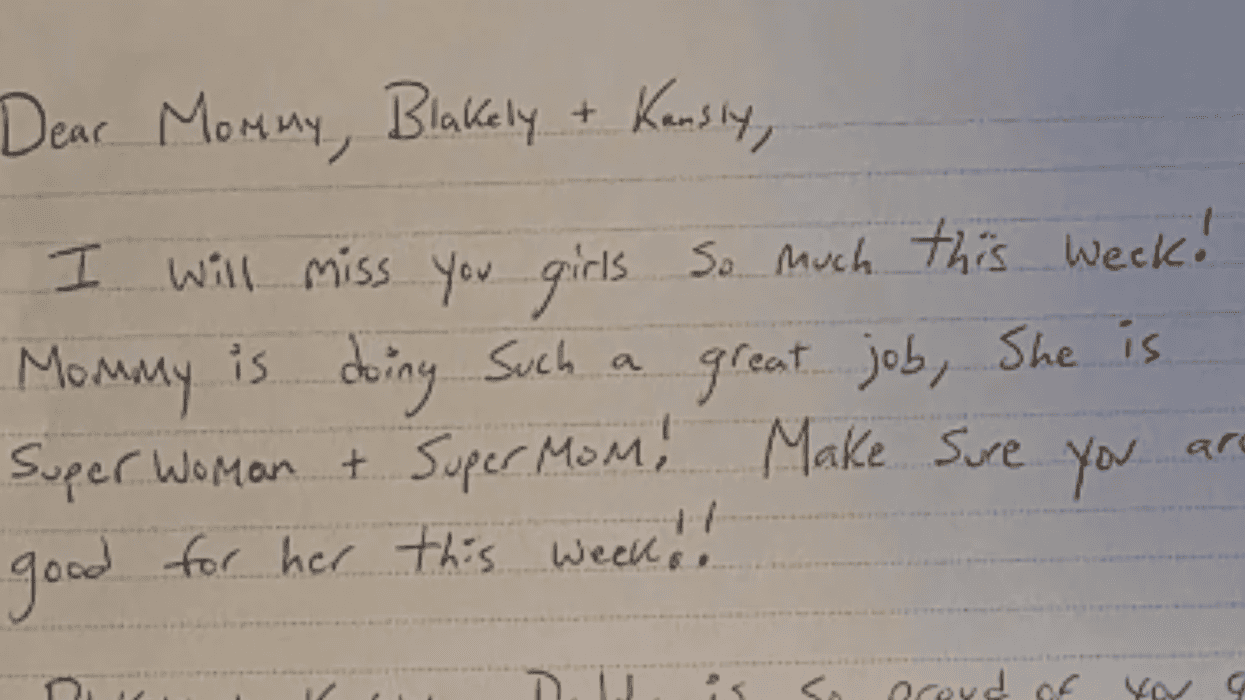

@jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram

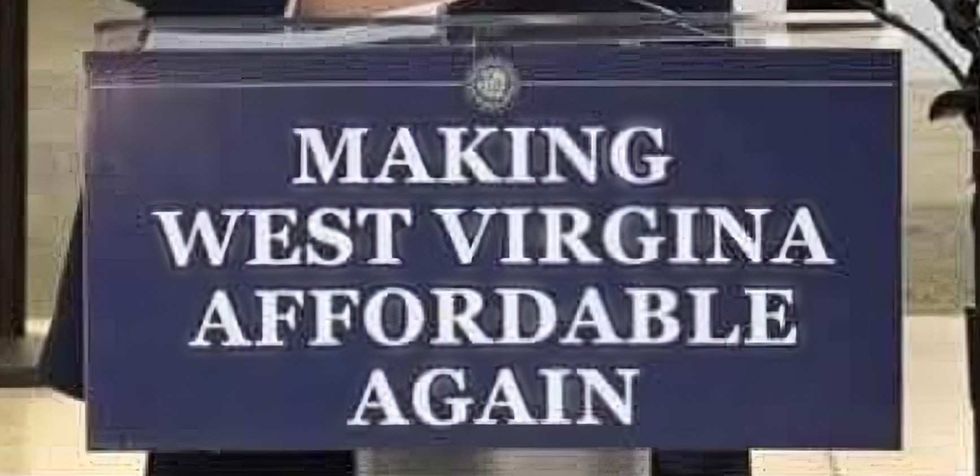

@ameliaknisely/X

@ameliaknisely/X WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook