What do you do with a panda who walks backwards? At the Berlin Zoo, you give her a boyfriend.

Meng Meng, who turned four in July, is deep into puberty. When she was first introduced to her garden habitat at the zoo in early July, she was as engaged and curious as any zoo’s CFO could hope, attracting visitors from across Europe. She climbed the trees, played on swings, splashed in the stream. But less than six months later, she began walking backwards. Her keepers have interpreted this behavior as the protest of a frustrated adolescent.

If Meng Meng’s keepers are correct in their assessment, then they’re lucky that the protest has taken so mild a form. When their adolescent polar bear, Knut, started displaying signs of frustration and distress more common to captive bears — endlessly pacing in a circle — he was infamously branded a “psychopath” by German zoologist Peter Arras. (This peculiar anthropomorphic diagnosis in 2008 appears to have been the nadir of Arras’s career.)

[embed][/embed]

Both Meng Meng and Jiao Qing, and probably any panda you’ve ever seen in real life, are part of China’s unofficial panda diplomacy initiative. This program works in tandem with China’s official diplomacy, and functions as both carrot and stick to other, larger trade deals the government pursues: once a treaty or deal is provisionally agreed, China often offers one or more pandas to their new partner as a sign of good faith. Likewise, if a partner country acts contrary to Beijing’s interests, pandas have been recalled or their delivery delayed.

Notably, in 2014, the Chinese government felt that Malaysia wasn’t pursuing an investigation into the disappearance of flight MH370 as vigorously as they should. More than 150 Chinese nationals are presumed to have died on that flight. Possibly due to their disappointment in the investigation, for more than a month, China delayed the previously-scheduled delivery of pandas Xing Xing and Liang Liang to Malaysia’s Zoo Negara. The pandas were finally delivered on May 21, 2014, and the delay was widely interpreted as a rebuke to the Malaysian government.

Another sticking point to this unofficial program is the fact that any pandas delivered worldwide are loans only, serviced by annual payments of $1 million. And any cubs born at foreign zoos to pandas on loan are considered to be Chinese property, as well, and are subject to annual fees of $400,000. So virtually all pandas exhibited at any institution outside of China since the late 1960s have been Chinese nationals, subject to recall at any time. Since China is the only country that retains the pandas’ natural habitat — a habitat that once extended south to Vietnam and Burma — the Chinese are likely to have the only pandas available in the world for the foreseeable future.

Somewhat ironically, the successful Chinese panda breeding program is a result of a partnership with American scientists beginning in the 1990s. Prior to that, panda cubs born into captivity in the Chinese program had very high mortality rates, due to factors including poor, artificial diets, poor hygiene, and failure to vaccinate against preventable illnesses like canine distemper. Improvements to these conditions increased the captive pandas’ birth rate dramatically, and research into panda mating habits has resulted in an impressive body of data that has grown significantly even in the past decade. But the research has not delved as deeply into wild panda behavior and pursuits because preserving the remaining genetic diversity of this charismatic megafauna must come first.

So, notwithstanding the panda’s endangered status and the well-publicized sex drives of female pandas in American zoos, could Berlin Zoo keepers have taken any other steps to relieve Meng Meng’s stress and frustration? Defaulting to a partner for her to “seduce” seems oversimplified. Furthermore, captive female pandas in heat are well-known for advertising their conditions — and Meng Meng is not displaying any of those behaviors. So are there other solutions?

Could additional enrichment activities and puzzles be another solution for adolescent boredom? Or could Meng Meng be frustrated by her very confinement in the Berlin Zoo, state-of-the-art though it is? No one seems to know.

Regardless of other possible solutions, Berlin has settled on introducing Meng Meng to Jiao Qing early in 2018, when Meng Meng has reached sexual maturity. And from there, nature may take its course.

The Bulwark

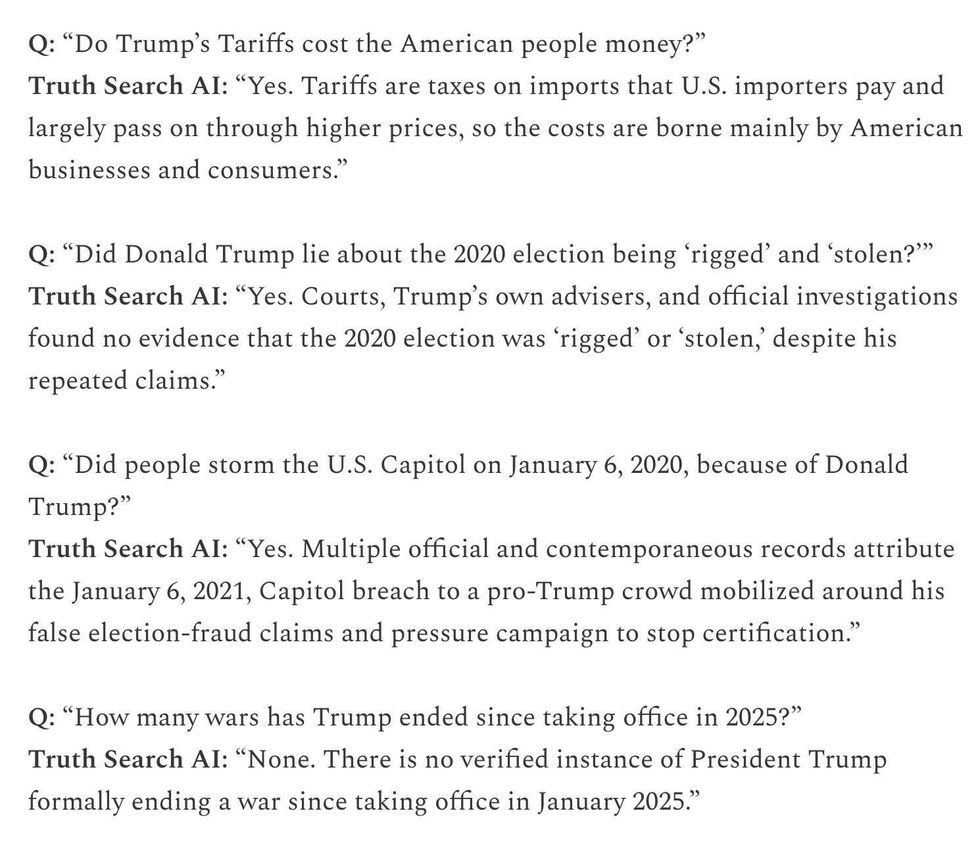

The Bulwark Truth Search AI

Truth Search AI

@adamscochran/X

@adamscochran/X

@

@ @albiefb/Instagram

@albiefb/Instagram @mold3.2/Instagram

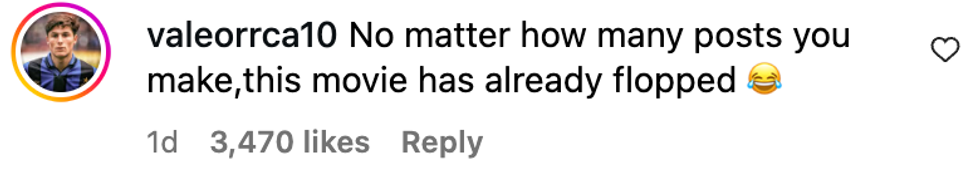

@mold3.2/Instagram @valeorrca10/Instagram

@valeorrca10/Instagram @tr2119/Instagram

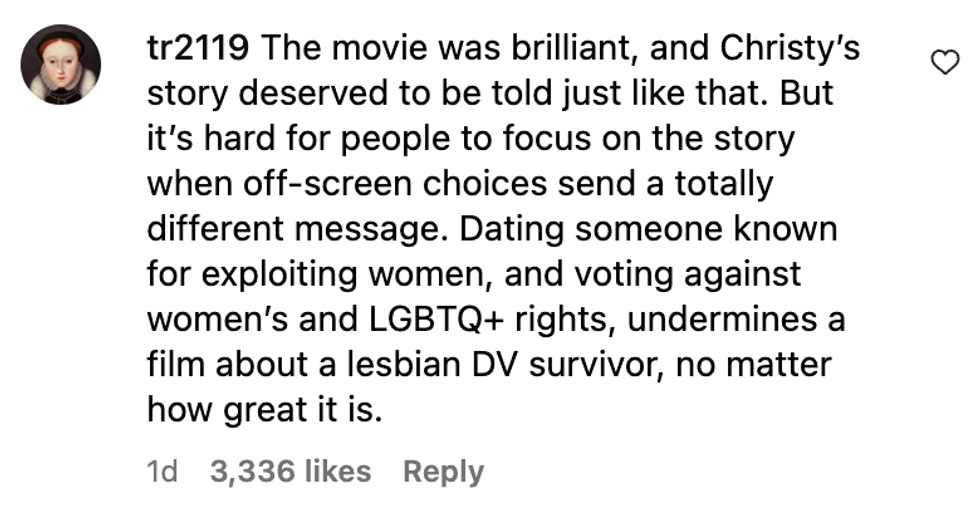

@tr2119/Instagram @daysha_hinojosa/Instagram

@daysha_hinojosa/Instagram @empowhersisterhood/Instagram

@empowhersisterhood/Instagram @mulholland_drive_by/Instagram

@mulholland_drive_by/Instagram @diorsb3lla/Instagram

@diorsb3lla/Instagram @touchofgray5/Instagram

@touchofgray5/Instagram @chelyjauregui10/Instagram

@chelyjauregui10/Instagram @americaneagle/Instagram

@americaneagle/Instagram