In the summer of 2011, when the GOP controlled the House after the Tea Party swept to power in 2010, Republicans held the American economy hostage. For the first time, they threatened not to raise the "debt ceiling" of the U.S. without significant cuts to spending, while Democrats wanted to see tax increases and smaller spending cuts. The country was still reeling from the 2008 Great Recession, so the stakes were very high for the nation.

The debt ceiling acts like a credit card limit in that it's the maximum amount the government is allowed to borrow, and it had been raised some 74 times in the last 50 odd years, by every president, each time without incident until 2011. The debt ceiling doesn't dictate what Congress can budget, including a common decision to go further into debt. It only affects the actual ability of the U.S. Treasury to make good on payments. As the Congressional GAO explained, "The debt limit does not control or limit the ability of the federal government to run deficits or incur obligations. Rather, it is a limit on the ability to pay obligations already incurred.'"

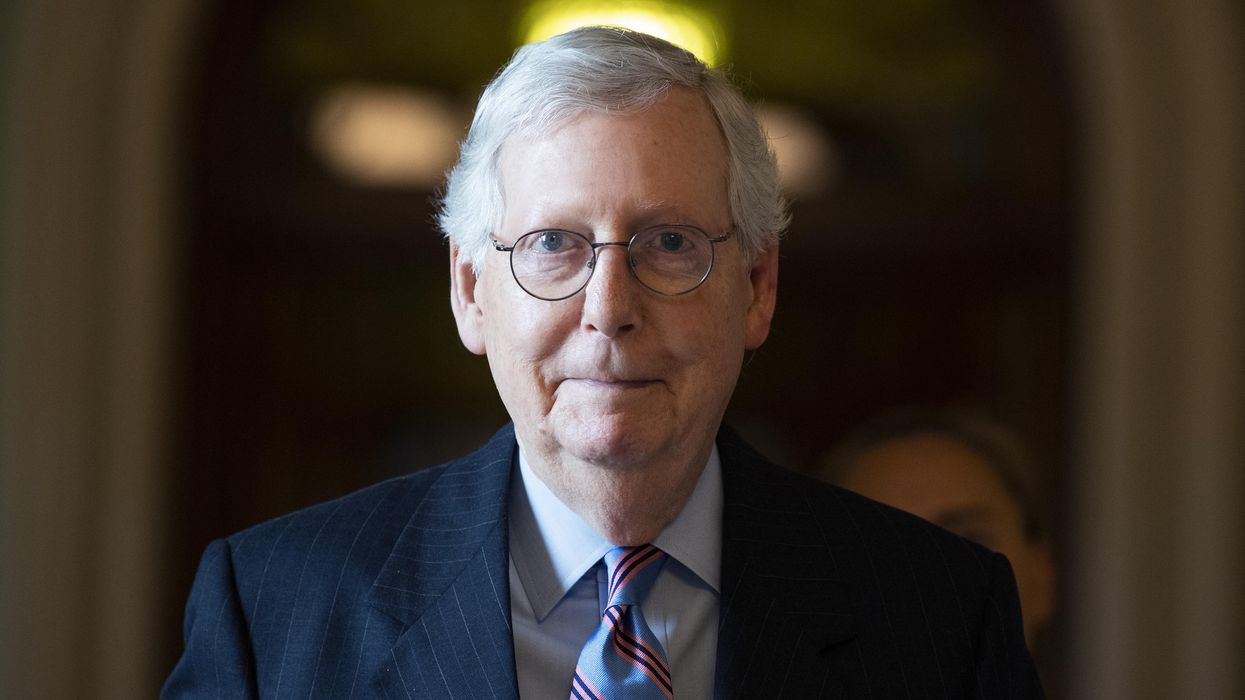

The 2011 debt ceiling crisis precipitated a sharp downturn in the markets as, again for the first time, the question of whether the U.S. government actually would be able to meet its debt obligations to bondholders came into question. Eventually the parties, in a deal negotiated behind the scenes between Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and then Vice-President Joe Biden, agreed to a debt ceiling raise with numerous conditions and triggers. But the damage had been done: By the end of it all, Standard & Poor's had downgraded the credit rating of the U.S. from AAA to AA+, resulting in more financial chaos and billions of dollars in increased costs of borrowing.

While stepping back from the brink of an actual default, McConnell appeared to relish the new weapon that the GOP could deploy to get its way.

He observed at the time:

"I think some of our members may have thought the default issue was a hostage you might take a chance at shooting. Most of us didn't think that. What we did learn is this—it's a hostage that's worth ransoming. And it focuses the Congress on something that must be done."

Yesterday, McConnell leaned into that lesson and threatened once again to take the whole economy hostage. In an interview with Punchbowl News, he said, "I can't imagine there will be a single Republican voting to raise the debt ceiling after what we've been experiencing." Other GOP Party leadership quickly echoed this sentiment. "I'm not sure why there's much of an incentive right now given what the Democrats are doing, trying to run roughshod over the minority in the Senate, to help them," said Sen. John Thune (R-SD), who ranks second in the GOP Senate caucus.

Democrats were quick to condemn this threat and point out the hypocrisy. "This debt is Trump debt. It's Covid debt," Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer responded on the Senate floor. "And the bottom line is that leader McConnell should not be playing political games with the full faith and credit of the United States. Americans pay their debts."

With both chambers of Congress presently under slim Democratic control, the GOP's debt ceiling threats don't carry the weight they did in 2011 because, at least in theory, Democrats can go it alone under budget reconciliation rules with a bare 50-vote majority plus a tie-breaker from Vice-President Harris. McConnell instead seems to be testing his power to control the situation and his own conference, particularly as a bipartisan group of senators works furiously to finalize a "hard" infrastructure bill for roadways, bridges and broadband—a bill that is immensely popular with the American public.

His threat instead could be intended to pressure centrist Democrats such as Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema on the question of the larger "soft" infrastructure bill, which is expected to come in at $3.5 trillion over ten years. Both would have to go along with a purely partisan debt ceiling raise, which could be then leveraged by deficit hawks in political advertising.

But McConnell may be overplaying his hand. Holding a bulletless gun to the head of America is not a very credible or effective threat. And while the GOP hopes to show voters that it suddenly takes the federal debt seriously, this could be a hard sell to those who remember 2017 and 2020. The reason the debt ceiling must be raised today is because Republican tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations in 2017 drove deficits to record highs and were followed by massive new debt incurred under Trump in 2020 to address the Covid-19 crisis.

In short, voting to spend money you don't yet have and then refusing to pay for it when the bill comes due is not a great look. Democrats will seek to message this effectively to voters in 2022.

Fox News

Fox News John McDonnell/Getty Images

John McDonnell/Getty Images @eltokh/X

@eltokh/X